The Art of the Artistic Director: Conversations with Leading Practitioners by Christopher Haydon (Methuen Drama)

Theatre Book Prize 2020 (for books published in 2019)

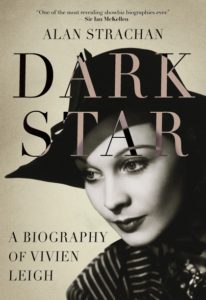

Dark Star: A Biography of Vivien Leigh by Alan Strachan has been awarded the Society for Theatre Research Theatre Book Prize (for books published in 2019).

The announcement was made remotely in lieu of the usual prize-giving ceremony at the Prince of Wales Theatre.

The winner had been chosen from the following short list (scroll down for images of these books and links to more information):

The Art of the Artistic Director: Conversations with Leading Practitioners by Christopher Haydon (Methuen Drama)

The Birth of Modern Theatre: Rivalry, Riots, and Romance in the Age of Garrick by Norman S. Poser (Routledge)

Dark Star: A Biography of Vivien Leigh by Alan Strachan (I B Tauris)

An Illustrated History of British Theatre and Performance by Robert Leach (Routledge)

Playwriting: Structure, Character, How and What to Write by Stephen Jeffreys and Dr Maeve McKeown (Nick Hern Books)

Shakespeare Spelt Ruin: The Life of Frederick Balsir Chatterton, Drury Lane’s Last Bankrupt by Robert Whelan (Jacob Tonson)

Theatre Book Prize Judge Professor Edith Hall, writes:

‘It has been a joy and a privilege to read all the books submitted, and being prompted to remember heady days and evenings in live theatres has been a boon during a period of national lockdown where we have been so starved of live entertainment of any kind whatsoever.’

On learning that Dark Star was the winner of the Theatre Book Prize author Alan Strachan made this response:

“I am delighted that Dark Star, my biography of Vivien Leigh, has won the STR Theatre Book Prize, especially given the strength of the short-list opposition. This happily reflects how the theatre and its related subjects continue to feature with publishers. It`s a shame that we cannot enjoy the usual reception ceremony this year and we must all hope that this most resilient of professions will come through this most testing of times. It will require positive actions rather than well-intentioned words from national and local government, with the recognition that the arts generally provide a form of investment in their huge contribution to the British Exchequer.

Without the V&A’s Theatre Collection, I would never have been able to write this book; the Vivien Leigh Archive, acquired from her family a few years ago, has been meticulously catalogued, providing me with a biographer`s treasure trove of previously unseen material — letters galore, her diaries for many years, photographs and scripts including her own script of Gone With the Wind, back in the news again. The book`s title – Dark Star — comes from astronomy; a Dark Star is one often masked or hidden behind shadows or by another star and I felt that Vivien Leigh`s career and personality had become both distorted and undervalued, clouded by the shadow of Laurence Olivier, her husband and regular stage partner over 20 years, by the destructively negative criticism of the most influential (but not always inevitably right) critic of the era, Kenneth Tynan and by her blinding beauty. I hope that my book goes some way towards reclaiming her as a major actor in her own right on stage as well as on screen.

I would like to thank publishers I B Tauris and Bloomsbury and my literary agents Michael Alcock and Andrew Hewson of Alcock & Johnson Ltd. I am also most grateful to Keith Lodvick and the staff at the Theatre Collection. Also big thanks to Howard Loxton and the STR for all its work and for its continuing support for this Award.”

The current pandemic forced us to cancel the live presentation of this year’s Theatre Book Prize but that doesn’t stop us sharing information about the books and the thoughts of the judges. Publishers submitted 44 titles ranging from those that fit in the pocket to a couple that need a lectern: quite a challenge to our judges whom we thank for their time and their diligence. Subjects range from a coverage of 2000 years of theatre in Britain to the production history of a single building, from the story of a female-led 18th century circuit company to records of contemporary immersive theatre, and this year for the first time a book produced manga style. (You’ll find the whole list by clicking on the 2020 Longlist in the black bar at the top of this page).

It is good to see that some among them acknowledge support in their writing or publication from the Society’s grants – plus, of course, the Society’s own publication. When titles range so widely and are produced with very different resources it isn’t a level playing field. In the end it comes down to the reader’s reaction. One year’s runner up might have won against different competition. What are the judges looking for? As their Chair Howard Loxton put it: “We are looking for books that record theatre history and practice, that increase our understanding of theatre making; celebrations of the past, clarion calls for the future; readable well produced books based on sound research or experience whether the work of a local theatre enthusiast or a high profile figure.“ But he doesn’t see the prize as just about winners. “How many of these books,” he asks, “would you find in your local or even a specialist bookshop? In the past you would have been able to inspect them at the prize giving not only through our website. We want to draw attention to all those that add to our knowledge and to the record of theatre, even if not prize contenders.”

You can learn more about all of 2019’s books through the links our Longlist listing gives to their publishers but we invited our judges, as in previous years, to divide the short list between them and tell us about those books and a few others they want to mention. Read on.

Donald Hutera

Dance critic for The Times of London, has written widely about theatre, especially on dance, mime and circus as well as curating festivals creating performances. He is co-author of The Dance Handbook and edited The Rough Guide to Choreography.

Serving on the judging panel of this year’s Theatre Book Prize hasn’t been just a relatively simple case of comparing apples and oranges. Instead it’s been more like juggling – and occasionally gorging on – a sometimes overwhelming array of, say, blueberries and coconuts, olives, guavas, grapes and limes, persimmons and tomatoes. Inevitably it is only particular fruits from this literary cornucopia that will stimulate any individual’s taste buds and, with luck, temporarily sate an unexpected appetite.

Having begun to nibble Shakespeare Spelt Ruin (publisher: Jacob Tonson) fairly early on in the months-long reading regime, I soon found myself craving increasingly larger portions of Robert Whelan’s thoroughly-researched, lovingly-crafted book. Subtitled The Life of Frederick Balsir Chatterton, Drury Lane’s Last Bankrupt, it is both a sympathetic biography of a significant but unjustly overlooked theatre manager and a panoramic, yet detailed, account of the times in which he operated. Between 1862 and 1879 Chatterton, while pursuing the elusive dream of shaping Drury Lane into a designated National Theatre, also did his best to strike a balance between escapist spectacle and so-called legitimate drama. Strewn with a fascinatingly idiosyncratic cast of real-life supporting characters, Whelan’s study of art and commerce is a deft, often sparkling portrait of a man as well as an accomplished piece of documentation about a juicy swathe of British theatre history. His fluid, pacey prose brings an era and its aesthetics to vivid life. As for Chatterton, his efforts yielded varying amounts of fortune and, ultimately, failure. I began to realise, well before the poignant closing chapters, how invested I’d become in someone whose triumphs and struggles were previously unknown to me.

Described in April De Angelis’ foreword as ‘a great bloke whose easy laugh set a room alight,’ Stephen Jeffreys was a playwright, teacher and, for a dozen years, Literary Associate of The Royal Court. By the time of his early death in 2018 he had already acquired something akin to legendary status. This was thanks, in part, to his acute, wide-ranging grasp of the art and craft of writing for the theatre. Distilled from the material Jeffreys used for his masterclasses, Playwriting (Nick Hern Books) is a wonderfully practical, at times almost thrillingly astute guide to the subject. Subtitled Structure, Character, How and What to Write, it was edited and, after Jeffreys’ terminal illness had progressed, eventually completed by his colleague Maeve McKeown.

The result is an inspiring justification of Stephen Daldry’s cover blurb: ‘What Stephen Jeffreys doesn’t know about playwriting isn’t worth knowing.’ No surprise, then, that the book is packed with insights and tips drawn directly from Jeffreys’ own instincts and practice. Whether the topic under consideration is establishing time and place, the six kinds of logic or three dimensions of character, the various types of plays, dialogue and subtext, the use of image systems or the nine categories of stories, always one senses the clarifying passion that fuelled his analysis. Valuable seems an understatement.

There were standouts among the many other books that, mainly due to the vagaries of collective decision-making, didn’t make it onto the shortlist. Here are some personal honourable mentions: Like Shakespeare Spelt Ruin, Alison Child’s Tell Me I’m Forgiven (Tollington) spotlights a person or, more accurately, two people whose celebrity, talent or cultural notoriety have pretty much been forgotten. Pitched as England’s first great female musical-comedy double-act, Gwen Farrar and Norah Blaney were among the top stars of Britain’s thriving revue and cabaret scene in the 1920s. Their highly polished performances, Child assures us, exuded a scarcely concealed intimacy and affection – qualities also present in the many photographs peppering her text. Child delineates the women’s enduring but complicated offstage relationship with skill and care, framing the ups and downs of their shared love and careers against a fizzy backdrop of family, friends and socio-political developments. Her book feeds tenderly off their and others’ personalities. I’m glad it exists.

I could say the same about Agency, subtitled A Partial History of Live Art and edited by Theron Schmidt (for Intellect Books), and The Punchdrunk Encyclopaedia (Routledge), written and prepared by Josephine Machon with the founding members and close associates of that titular company. If I’ve come to view these distinctive volumes as a rightful pair, it is perhaps because within the context of the approximately forty-five, generally more conventional contenders for this year’s prize they kind of belong together. Each book sheds rewarding light on many ideas, impulses and achievements from two important strands of contemporary performance. Focusing on the two decades since the Live Art Development Agency was established in 1999, organised around five themes (bodies, spaces, institutions, communities and actions) and featuring essays by and conversations between a whole tranche of envelope-pushing, taboo-busting artists, Agency covers an impressive amount of ground. The Punchdrunk Encyclopaedia, meanwhile, is a simultaneously sprawling yet in-depth, multi-faceted examination of the origins and evolving working methods of one the world’s leading immersive theatre companies. Having kept tabs on their nearly twenty-year ascendance from ambitious fringe experimenters to globally-acclaimed, mainstream innovators, for me the book’s unusual format – an alphabetical, cross-referencing arrangement of subject matter into which longer essays and think pieces are sprinkled – makes perfect sense. One to dip in and out of.

Finally there is my wild card: Brian Kulick’s The Secret Life of Theater, subtitled On the Nature and Function of Theatrical Presentation (and published, again, by Routledge). Although the author could hardly be accused of eschewing academic jargon, and the multiple-angled exploration of his core conceits does give off the odd whiff of pretension, there are probably enough bold, imaginative thought processes at work in the book to engage, excite and lure me back to its pages. Strange and heady fruit indeed.

Graham Cowley

Theatre producer, formerly of the Royal Court and Out of Joint and now running Two’s Company

In The Art of the Artistic Director Christopher Haydon has produced a most unusual and important book. A former Artistic Director of the Gate Theatre in London, he sets out to mine the experience of other people who run theatres in Britain and America, in an attempt to explore how a wide range of such directors tackle this supremely complex job. The 20 directors he talks to each have individual answers to the questions he asks and to the challenges they face. What emerges is a remarkable document, revealing the mixture of pragmatism and ideals, regrets and successes, artistic obsessions and nut-and-bolts practicalities that characterise the lives of all Artistic Directors, while showing us the myriad individual ways in which these remarkable people deal with the job.

As you’d expect, there were several biographies submitted for this year’s prize. Many of them made for fascinating reading, but we were all agreed that far and away the star was, indeed, Alan Strachan’s biography of Vivien Leigh, Dark Star. First of all, it was a joy to read. A vivid mixture of factual story and anecdote, peppered with casual details which can only be the product of meticulous and wide-ranging research, and with the benefit not only of Vivien Leigh’s diary and those of others, but of material from her life never before released. As Edith Hall remarked when we first discussed the books, this is likely to be the definitive biography of Vivien Leigh.

Alan Strachan was clearly familiar with the many previous biographies of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier, who was of course her key relationship. A further reward of this book is the equally detailed and incisive examination of Olivier’s world and life, which had so much bearing on hers. Alan Strachan’s superior research and acutely inquiring mind allow him to correct earlier canards, including the rumour of Olivier’s gay fling with Danny Kaye. Strachan definitively demolishes this old story and we emerge with a portrait of a golden couple, doomed to crash apart because of Vivien’s bipolar disorder. And what is so absorbing is that, although he tells a chronological story, it never feels like “and then this happened”. The fascinating background detail includes stories of Kenneth Tynan, Basil Dean, Binkie Beaumont, Tennessee Williams, Peter Finch and many others. It’s a thrilling read.

Dark Star didn’t have it all her own way, however. Among the other biographies was an enjoyable read, Ian McKellen by Garry O’Connor, who has the advantage of having known his subject personally since they were at Cambridge together. Entertaining and gossipy, and his research augmented by a series of conversations with McKellen himself, O’Connor gives us a portrait of an actor growing in stature who eventually is able to use his celebrity to become a standard-bearer for gay liberty.

David Suchet’s book Behind the Lens reveals his considerable talent as a photographer and takes an interesting path, seeking to show us his life and experience through his eyes. The correspondence between his words and his pictures (the book is lavishly illustrated) is never less than interesting and often revealing. He has a seriously good eye for an image, which reflects back on his feeling for character and situation. He takes us through his career and life and world view.

Less revealing, only because its subject spent his life in the public eye, is Louis Barfe’s biography of Ken Dodd, Happiness and Tears. But the book is a useful overview of the long career of a zany comic addicted to performing, a fountain of one-liners who straddled the end of the variety age and built up a huge following on television. But Barfe is also able to peep behind the public curtain and reveal something of Doddy’s personal convictions, causes and financial muddles.

A more personal account is Diana Devlin’s Sam Wanamaker, A Global Performer, made possible because she worked alongside him to bring about his dream of recreating Shakespeare’s Globe, from his earliest days of fundraising. Wanamaker had a reasonably successful career as actor and director, but it is for the Globe that he is best known – and that part of his story only starts in the last third of the book. This is where the bobbing and weaving that characterised Wanamaker’s career up to here comes into its own, and the detail of the many rivalries, machinations and sheer American chutzpah which brought the Globe to fruition is fascinating.

Lenny Henry’s book Who Am I, Again? is a frank – very frank – description of his early life, in which he lays his family and background before us. His way out of being beaten up by racist school-fellows was to make fun of them, and his talent for mimicry and natural ebullience landed him stand-up spots in Dudley ballrooms and clubs. Here is a bewildered teenager, whose career is gathering momentum but without anybody to guide him through the maze of life, trying to find what people wanted of him and who he was himself. I found his story moving, and a stark reminder of how racism still infects our everyday lives. And it’s endearing to see how his memory of the most acerbic criticism and his worst reviews is so crystal clear – as with all of us. And he includes 13 very useful tips for young comedians at the end!

Edith Hall

Professor in the Classics Department of King’s College London, author, broadcaster, co-founder of the Archive of Performances of Greek and Roman Drama and a consultant to theatres. Greek Tragedy and the British Theatre, 1660-1914 (co-authored with Fiona Macintosh) was short-listed for the Theatre Book Prize in 2005.

The art of theatre was born in the competitions held at festivals of the Greek god Dionysus, where winning first prize was an enormous honour; the first books on drama and theatre were written in classical Athens in the 5th and 4th centuries BCE. Although we judges independently and unanimously picked out the same book as winner of the first prize, our shortlists were by no means identical. I was highly impressed by the work that had gone into George Cole’s Betrayed: The Story of Harold Pinter’s Betrayal (Aharta Publishing): a detailed study of several major productions and versions produced on radio, TV and in film, it contains a staggering number of insightful interviews with practitioners and will become the go-to book for anybody performing, directing or studying Pinter’s classic reverse-chronology drama of secrets, lies and adultery.

I was also blown away by Berta Joncus’ Kitty Clive: The Fair Songstress (Boydell Press). Clive is a fascinating subject, as an incomparably versatile singer who made an incalculable impact on Georgian playhouse practice. This book is a model of conscientious research and elegant writing, but it also asks completely new questions about the evolution of music in theatre and musical theatre in 18th-century Britain and the strategies talented women needed to develop for coping with institutionalised male power. This is simultaneously an outstanding work of scholarship and an extremely good read.

Amongst the shortlisted works, it was the combination of meticulous scholarship with writing of unusual verve that caught my eye in Norman S Poser’s The Birth of Modern Theatre (Routledge). This is not just another book about David Garrick, but a rollicking account of the personalities that made the world of the mid-18th-century London stage so vivid and exciting. The rivalry between actor-managers and leading ladies, the adulterous liaisons, bigamy and even a charge of sodomy against Samuel Foote of the Haymarket, create an impression of a ‘celebrity’ culture all too familiar today. Poser conveys the sheer noisiness of the far from deferential audiences, and the serial innovations that kept them attending, sometimes fighting physically for the unallocated seats. Shakespeare was re-envisaged as a master of naturalist psychology and the delineation of subtle emotion; the theatre press was virtually invented from scratch at this time, and multiplied sevenfold in volume. What Poser brings out best is the radical changes wrought by this generation of professionals in the entire culture of the theatre industry, introducing many elements that have survived to be still recognisable today.

Mark Brown’s Modernism and the Scottish Theatre since 1969 (Palgrave Macmillan) stands out for its lucidity and the way it draws together discrete phenomena into a compellingly persuasive narrative. Brown knows more about theatre in Scotland than almost anyone else alive. He has not only seen how remarkable are some of the achievements of the last half century, but that apparently disparate material can be presented as an organic history of a very distinctive set of theatre practices. He sees them as beginning with the iconoclastic work of the Glasgow Citizen’s Theatre, especially its all-male Hamlet of 1970, and evolving with anti-naturalistic and daring productions of Genet and Brecht—that is, European Modernist theatre quite unlike much of what was being produced in the British metropolis. The book contains some illuminating interviews, notably with the playwright David Greig. The vivid discussion of Liz Lochhead’s adaptations of ancient Greek drama will prove indispensable. I would have liked to see more attention paid to the work of the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh and certainly to the politically committed socialist theatre of John McGrath. But Brown’s contribution will inevitably become a central text in future understanding and appreciation of theatre in Scotland and it is a though-provoking, polemical read.

Much more substantial in scale, Robert Leach’s massive An Illustrated History of British Theatre and Performance (Routledge), which extends over more than 1,200 pages, succeeds in turning the encyclopaedic form into something more exciting. Within these two hefty tomes, there are 150 short chapters, which are easy to read and digest in one go. Leach has gone out of his way to appeal to a younger audience with strong interests in identity politics, including much information on, for example, gay, female and ethnically diverse practitioners. He has a talent for placing particular performative phenomena in a wider social, cultural or intellectual context, albeit it with a light touch. As a classical specialist I would have liked quite a bit more on the performances in ancient Roman theatre and amphitheatres, but this work is a major achievement. It should be on the shelf of every secondary school and department of theatre or drama in the land. Laden with interesting illustrations, it contains pedagogically useful timelines, bibliographies and glossaries. The level of writing is well sustained and the variety of material covered impressive.

Writing about theatre presents a multitude of theoretical challenges, which in turn produce multifarious types of writing and documentation. That variety is reflected in the books discussed here but they share well-defined structures and parameters, an appealing prose style, meticulous documentation and above all an enthusiastic commitment to their subject matter and why it matters. It has been a joy and a privilege to read all the books submitted, and being prompted to remember heady days and evenings in live theatres has been a boon during a period of national lockdown where we have been so starved of live entertainment of any kind whatsoever.

Previous winners (by year of publication)

2018-Year of the Mad King: The King Lear Diaries by Antony Sher (Nick Hern Books)

2017-Balancing Acts by Nicholas Hytner (Jonathan Cape)

2016 – Stage Managing Chaos by Jackie Harvey with Tim Kelleher (McFarland)

2015 – The Censorship of British Drama 1900-1968 by Steve Nicholson (University of Exeter Press)

2014 – Oliver! by Marc Napolitano (Oxford University Press)

2013 – The National Theatre Story by Daniel Rosenthal (Oberon)

2012 – Mr Foote’s Other Leg by Ian Kelly (Picador)

2011 – Covering McKellen by David Weston (Rickshaw Publishing)

2010 – The Reluctant Escapologist by Mike Bradwell (Nick Hern Books)

2009 – Different Drummer: the Life of Kenneth Macmillan by Jann Parry (Faber & Faber)

2008 – Theatre and Globalisation: Irish Drama in the Celtic Tiger Era by Patrick Lonergan (Palgrave Macmillan)

2007 – State of the Nation by Michael Billington (Faber & Faber)

2006 – John Osborne: A Patriot for Us by John Heilpern (Chatto & Windus)

2005 – 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare by James Shapiro (Faber & Faber)

2004 – Margot Fonteyn by Meredith Daneman (Penguin/Viking)

2003 – National Service by Richard Eyre (Bloomsbury)

2002 – A History of Irish Theatre 1601-2000 by Christopher Morash (Cambridge University Press)

2001 – Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840-1880 by Jim Davis & Victor Emeljanow

– (Iowa University Press/University of Hertfordshire Press)

2000 – Politics, Prudery and Perversions…. Censoring the English Stage 1901-1968 by Nicholas de Jongh (Methuen)

1999 – Garrick by Ian McIntyre (Allen Lane)

1998 – Threads of Time by Peter Brook (Methuen)

1997 – Peggy: the Life of Margaret Ramsay, Play Agent by Colin Chambers (Nick Hern)

Book Prize Archive

The Book Prize has been awarded each year since 1997.

Click on the links for more information.

2019 (books published 2018)

2018 (books published 2017)

2017 (books published 2016)

2016 (books published 2015)

2015 (books published 2014)

2014 (books published 2013)

2013 (books published 2012)

2012 (books published 2011)

2011 (books published 2010)

2010 (books published 2009)

2009 (books published 2008)

2008 (books published 2007)

2007 (books published 2006)

2006 (books published 2005)

2005 (books published 2004)

2004 (books published 2003)

2003 (books published 2002)

2002 (books published 2001)

2001 (books published 2000)

2000 (books published 1999)

1999 (books published 1998)

1998 (books published 1997)