News

28 April 2020 / Grants and Awards

Radium Dances

Lucy Jane Santos received an award in 2019 for her work on the use of radium in popular entertainment. Lucy is a freelance writer and historian with a special interest in popular science and the history of everyday life. She writes and talks (a lot) about cocktails and radium. Her debut non-fiction Half Lives: The Unlikely History of Radium will be published by Icon in July 2020, and she has an absolutely fascinating blog, highly recommended. She writes for us here:

Exploring the uses of radium in British Theatre in the first half of the twentieth century

This project is focused on the use of the radioactive element radium in British theatres, both as part of costuming and as a plot theme. It was proposed to study four main performances: Loie Fuller’s Radium Dances (1904, various venues), The English Pony Ballet (1904, Alhambra and various venues), the play The Radium Girl presented by the company of George Foster (1915, various venues including The Palace Theatre, Blackpool) and the stage illusion Vera the Radium Girl created by master magician Valentine Walker (1919, various venues).

Thanks to this grant I was able to visit the New York Public Library, the British Library (on multiple occasions), the Wellcome Library, the V&A Theatre and Performance Archives and the National Archives to name but a few.

Here is a summary of my findings. This research will also feature in my forthcoming book Half Lives: The Unlikely History of Radium to be published by Icon in July 2020.

Loïe Fuller’s Radium Dance

Loïe Fuller was an American actress and dancer who is now best known for her pioneering of theatrical lighting techniques. In 1902 she wrote to Marie Skłodowska Curie and Pierre Curie to ask for their help in making a costume for her new dance, which would include ‘butterfly wings of radium.’

Loïe was keen to incorporate radium salts into the fabric of her dress but needed advice on the best way of doing so. She had been inspired by reports of a phenomenon that the Curies had witnessed in their laboratory when they observed that while radium chloride looked like common salt in the daytime, it actually glowed in the dark. This effect was subsequently understood to be caused by its radiation agitating the nitrogen that is naturally present in the air. This vibration creates a buzz of energy, which is perceptible as a shimmer of light, just luminous enough to be visible in the dark.

The Curies, warning Fuller about the potential dangers of experimenting with the substance, gently dissuaded her and steered her towards using other less dangerous materials to create the desired special effects. Pierre even helped Fuller set up a laboratory in Paris for her experiments into other substances. It is not clear why the Curies warned others but seemed to be ignorant of the risks to themselves, but they were concerned for their friend Fuller, perhaps because she did not have the same scientific background as they did.[1]

Loïe Fuller eventually debuted what she called the Radium Dance in early 1904 performing it with her dance troupe in Paris, London and the United States to great acclaim. One of her London performances was memorably described by a journalist who had a private view of the spectacle.

‘Through a slit in the curtain opposite a green glow is seen. Suddenly an apparition comes into view. It is a vague form, only distinguished by the hundreds of tiny glow worms which it seems to carry on its flowing raiment. The tissue of twinkling stars floats about, circles, sweeps along the floor, or is wafted up until it is shaped into a sort of great luminous vase. The dancer’s face is never seen, her form is vaguely divined when outlined by the glowing lights. The apparition vanishes, to be followed by another more weird still.

Above a perfectly invisible head, which you only suppose to be there, shines a bluish halo. Below, clothing an unseen figure, is a long robe, which is merely one great patch of the same ghostly light. The apparition slowly moves to a solemn rhythm, seems to invoke heaven, the halo being thrown backwards when the head is as you conclude, uplifted, and finally, the robe of light sinks on the floor, when you infer that the figure kneels. The second ghost vanishing, a third appears, a monster glowing moth, with shining antenna a foot long, eyes which are globes of light, and wings six feet high, glittering with luminous scrolls in all colours. The moth flutters round and round the studio, then out of our sight, but reappears instantly, accompanied by a smaller, glowing white butterfly, which beats its wings over the monster luminous insect’s head. Lamps being relit, we are bought back to reality out of ghostland, and having an opportunity of examining the dancer’s dresses, find that they are made of a peculiar kind of silk completely impregnated with certain fluorescent salts. In complete darkness only the portions of material thus rendered luminous are visible.”[2]

Her directors’ notes, written in poetic form, explain a little bit more about the effect she was trying to achieve:

“The Radium is a soft-strange light.

It is like the moon

it throws no rays

it is not brilliant

and it must be seen in absolute darkness

It is a new unknown light

and should not be looked upon

or judged by a bright light

and it should be seen very near.”[3]

Loie’s personal journals, currently housed in the New York Public Library, make it clear that she was very knowledgeable about radium and the effects of radioactivity. She made clear her conclusion to the New York Times in 1911 telling a journalist that she had found radium to be too problematical to use in her costumes and had found another substance to make her costumes glow in the dark. Unfortunately, I have not, yet, been able to find a trace of what this was.

Radium Dances

Loïe was not the only person interested in the potential of radium in the theatre especially once it was realised that if you added a sticky substance to radium chloride , then you could paint objects and make them shine in the dark. While this sounds impressive, glow-in-the-dark paints were not new: they had been developed in the 19th century. The most common material for making this style of paint, which was especially popular for creating theatrical effects, were phosphors: which needed to be illuminated in advance for it to work. The phosphors also needed periodic recharging or replacing to stop it fading within a very short space of time. Glow-in-the-dark paint made with radium, so the theory went, would eliminate this issue and would only require minute traces of radium salts to make a permently glowing substance that didn’t need any external source of illumination.

Whilst there were some earlier experiments with creating radium paint the first person to attempt to make radium glow in the dark paint for the theatre seems to be Lester D Gardner who was an engineer. Gardner debuted his radium paint at an event which came to be known as the ‘Sunshine Dinner.’

This prestigious society event, which was for alumni of MIT and the cream of New York society took place in February 1904. Gardner was head of the entertainments committee and they presented a series of entertainments that astounded the 150 men (and it was limited to men) present and fascinated those who read about it afterwards. But, as with everything surrounding radium at this period, it is quite tricky to separate the facts from the fictions regarding what actually took place. All published accounts agree that after the meal the dining room was darkened and that luminous paint was used to significant effect, but they differ on some key points. Some claimed that there were glow-in-the-dark dancing skeletons and balloons. There was even a report of a glowing human skeleton, said to be that of the founder of MIT.[4] More bizarrely the decorations apparently included two glow-in-the-dark pasteboard chickens fighting over an egg: a visual reference to a speculation made earlier that year by Mr Hobbs, a farmer from Washington, that mixing radium with chicken feed could make ‘radio-eggs’ which would potentially hard boil themselves.[5]

The huge amounts of attention that his event generated in newspapers around the world would have pleased Gardner, who had an excellent reason to extoll the virtues of luminescent paint. His firm, the L.D. Gardner Company of New York, had spotted a gap in the market and, thanks to the publicity surrounding the Sunshine Dinner, had now been given a worldwide platform to advertise their product: ‘Radium Paint’.

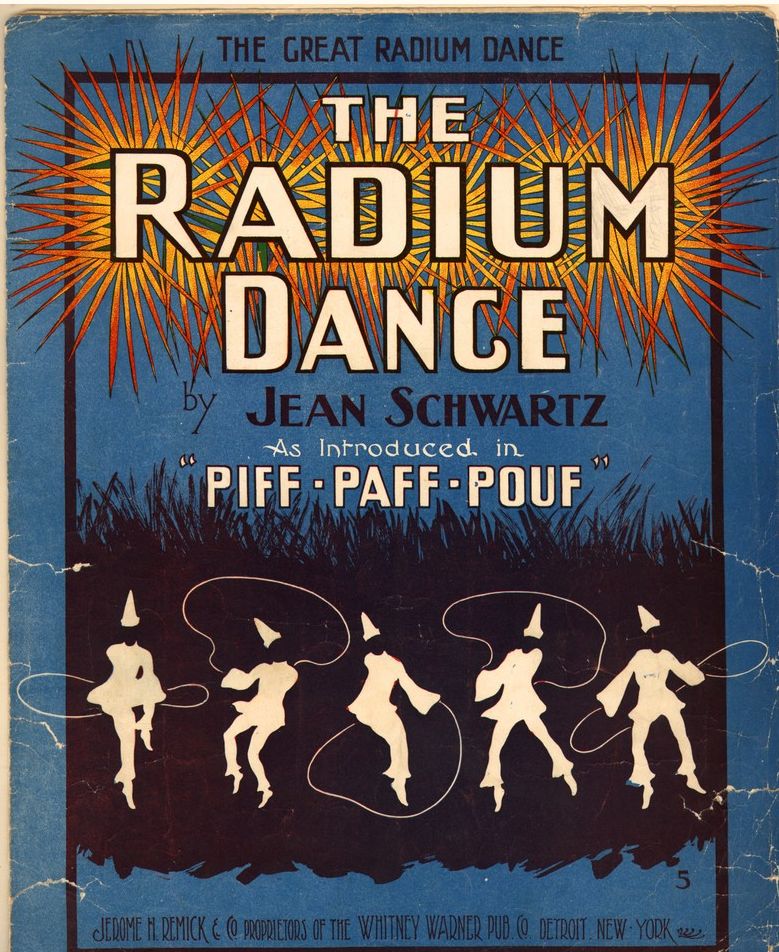

Gardner had already made an agreement with the legendary theatrical producer F.C. Whitney who was about to open the musical play, Piff! Paff! Pouf!, at the Casino Theatre on Broadway. Whitney, who was said to have bought the exclusive rights for the use of radium paint in the US from the L.D. Gardner Company,[6] also hired the designer Caroline F. Siedel to create costumes for a dance sensation that was sweeping America: The English Pony Ballet. This vaudeville act was a group of eight teenage girls who were specialised in a strict synchronised style of dancing said to imitate horses’ movements with exact precision and perfect harmony.

After this happy plot resolution the stage was plunged into darkness, and the orchestra (the baton of the conductor was also apparently painted with glow-in-the-dark paint) began playing the piece of music written especially for the play by Jean Schwartz: the Radium Dance. Half of The Pony Ballet appeared on the darkened stage dressed as Pierrots with sugarloaf hats and skipping ropes, the other half were dressed as Pierrettes: with coronets, ribbons and special shoes all glowing in the dark. They now performed the dance, which seems to have involved a lot of synchronised skipping (using ropes that were also painted) in time to the music: a rather conventional ragtime number with a fast beat and a catchy tune that had nothing to do with radium.

The Radium Dance was such a success in Piff! Paff! Pouf! and so many people wanted to watch it that the number was added (complete with the exact same costumes) to the last scene of the musical play All the Year Round which caused a sensation when it was performed at the Alhambra Theatre, London in May 1904. Again the glow in the dark materials were provided by Lester Gardner under an exclusive arrangement.

On both sides of the Atlantic these performances stimulated a lively debate amongst theatre goers and reviewers as to whether these Radium Dances were performed using (the very costly) real radium paint or whether the glow-in-the-dark effect was due merely to ordinary phosphorescent paint that had been deceptively billed for publicity purposes. In response to these apparently damaging claims Gardner’s lawyer, Robert S. Allyn, wrote a very indignant letter to the editor of The New York Times to clear the good names of his client and the producer Whitney, who had presumably paid a premium for this special effect. ‘This paint does actually contain radium and does not require any phosphorous whatsoever’ stated Allyn before adding that Gardner was in charge of overseeing the preparation of the paint, as a personal guarantee to its authenticity.[7]

The claim that Gardner’s much lauded ‘radium paint’ did not actually contain any radium was a serious one – with the potential to damage not only his fledgling business but the popularity of the many productions that now relied on the publicity surrounding the Radium Dance to draw in the curious crowds eager to see the mysterious radium in action.

There are a few clues still available which indicate that Gardner, at least, had simply tapped into the commercial cachet of radium without going to the expense and trouble of sourcing real radium salts (and that his lawyer was either uninformed or part of the deception). For a start, a trawl through the online archives of the United States Patent and Trademark Office show that instead of taking out a patent (which would have detailed and protected the highly desirable process for creating the paint) Gardner simply filed an application to trademark the word ‘radium’ which would have had the effect of giving him exclusive use of the term in the categories that were applied for: of ‘prepared colors for printing and painting’[8] and for ‘theatrical costumes.’[9]

A further tantalising clue is preserved in the Bella C. Landauer Collection of Business and Advertising Ephemera held by the New York Historical Society: a rare flyer for the L.D. Gardner Company claiming to be printed with their ‘wonderful radium ink.’ This document, which dates to around 1905, shows a grinning skull on a dark black background. The text directs the reader to: ‘Hold this picture to a bright light or a window, for a minute, and then look at it in an absolutely dark closet.’

The Radium Girl Illusion

The escape artist Val Walker had begun his career working as an electrical apparatus makerbefore joining the navy.[10] His new career began onboard the HMS Invincible when he escaped from a naval tool chest and earned himself the nickname ‘The Wizard of the Navy.’

But it was Vera the Radium Girl (also known as the Radium Girl Illusion) that secured his place in magic history.

Walker devised the trick while he was appearing at the legendary magic venue John Nevil Maskelyne’s St George’s Hall sometime in 1919, the year after the First World War had ended and for an audience desperate for a bit of light relief.

The illusion, a form that is well known to us now, was a novel sensation for its contemporaries. The audience was presented with a large box: slightly raised from the ground on casters to show that there was no trap door underneath. The front and the back of the box are left open, and the magician bangs on the sides and on the roof to prove that it is solid. An assistant – the more beautiful, the better – is called upon, and is restrained inside the case: with leather straps around her neck, her upper arms and her feet. Finally, the front and the back panels of the box are fitted and secured. She is completely trapped. The magician turns the box around so the audience can inspect it for the last time before poles inserted into the pre-drilled holes in the box, sheets of metal are wedged through– through her head (there is helpfully the silhouette of a woman drawn on the outer box, so the audience are clear what is happening), through her chest and through her legs: cutting her into pieces.

The magician then reverses the steps, removes the doors and voila – the assistant appears unharmed.

Walker eventually mostly retired from the stage in 1924, gave up his membership of the magic circle and resumed life as an electrical engineer in Dorset.[11]

The trick, however, was briefly revived by the magician Jeffrey Atkins, who performed is (using a custom designed box made by Walker six months before he died) on an episode of the popular BBC television programme The Paul Daniels Magic Show in October 1980.[12] The illusion, in a slightly different form, has survived however and the genre of tricks are collectively known as girl in the box.

The reason why Walker named the trick after radium has not survived but it may even have been a slight confusion between the different forms of radiations. Surviving photographs of the trick (https://www.flickr.com/photos/109352745@N04/albums/72157637913599165/) show that the silhouette of the ‘Radium Girl’ are reminiscent of an X-ray photograph.

Radium Girl Revue

The ‘Radium Girl Revue’ was a novelty revue presented by the company of British theatrical producer, George Foster in theatres between November 1915 and September 1916. The revue was staged at (amongst many more) the Victoria Palace in London, the Stratford Empire, the Empire, Wigan and at the London Coliseum

The cast included the popular American comedian, Alva York playing the key roles of Miss Innocent Lamb and (later as the plot develops) The Radium Girl. Frank Ellison and Syd Howard played Zigani and his assistant, Nassarac. The play was based on a book written by Worton David with lyrics by A J Mills and music by Benet Scott.

The central character is Zigani, a fraudulent Egyptian fortune teller from New York City. The action starts when a couple seeks Zigani’s advice as they are about to get married. The fortune teller (who had been bribed by Slick Sal, a jealous rival for the affection of the male character) warns the fiancé about her betrothed’s shady past leading to a split. Zigani quickly repents his involvement in their devastating break up and resolves to bring them back together. Not content with this plot line Zigani also has an announcement to make: ‘a life giving fluid – a kind of radium that will electrify the whole world.’ And the thing he wants to do with this discovery is to turn ‘Miss Innocent Lamb’ into a new kind of revue artist. Miss Innocent Lamb, a simple country girl, is persuaded to go along with the plan and drinks his ‘marvellous fluid.’

Here the script is rather intriguing: ‘She drinks. Gong. Black out. Radium effect during which she is seen wakening to life.’ Whilst it isn’t clear what the radium effect was (and I cannot find any contemporary descriptions) it may be that there was a spotlight on the actress. In any case she wakes up and sings the song ‘The Radium Girl’

Oh! The darkest night in a blaze of light.”

You hover near my Radium Girl

And your bright eyes gleam

Like a big sunbeam

As you flutter by

My golden butterfly

I’m trying to catch you but when I draw near

Like a will of the wisp you disappear – dear

CHORUS

Oh You Radium Girl

Oh Your Radium Girl (You are a vision so delightful)

First you are here and then you are there

Fascinating everywhere

You’re so dazzling, you’re mysterious – I’m delirious

You’ve such a wonder power- you’ve a power, every hour to bewitch us all

My heart, my brain are all awhirl

(You’re rarer than a pearl)

That radiant light that shines in your eyes

Is like a radiant star in the skies

Shine on my Radium Girl (shine on my radium girl)

Unfortunately the treatment also causes her to go rather wild in the pursuit of pleasure and dancing and she creates a great deal of mischief for everyone. The final scene (described as a scintillation) is at The Radium Ball. Again little evidence survives to say what that involved in terms of staging but the Coventry Evening Telegraph described it as being in black and white.

Whilst little evidence has been unearthed about The Radium Girl Revue in Britain it is possible that its staging was influenced by the Ziegfeld Follies of 1915 which ran for a total of 105 performances at the New Amsterdam Theatre on Broadway between June 21 and September 18 1815. Here the song ‘My Radium Girl’ was performed by Charles Purcell and the Radium Girls and the scene was set in ‘Radiumland.’ Surviving material makes clear that this scene was a black background contrasting against the actor’s white clothes to create a black and white effect. It is tempting to suggest that The Radium Ball of the British production was based on a similar arrangement.

The Radium Girl Revue was described by the Lord Chamberlain Office as a ‘lively but utter nonsensical revue’ and based on the script that seems a rather fair assessment.

Lucy’s book is out in July and can be pre-ordered from various sources.

[1] Loïe was a self-taught scientist who benefitted from friendships with eminent scientists who helped her with her experiments including William Crookes, Thomas Edison and the astronomer Camille Flammarion as well as Pierre Curie.

[2] Daily Telegraph, 2 March 1904, p. 11.

[3] Loie Fuller papers, New York Public Library

[4] Mansfield Advertiser, 4 May 1904, p4.

[5] Daily Mirror, 9 February 1904, p5; Mansfield Advertiser, 4 May 1904, p4.; Daily Times, 19 December 1903, p3.

[6] Central New Jersey Home News, 2 April 1904, p7.

[7] The New York Times, 13 April 1904, p10.

[8] Trademark 42,339. US Patent Office. Filed 23 February 1904.

[9] Trademark 42,465. US Patent Office. Filed 25 March 1904.

[10] From the 1911 Census.

[11] He did return briefly under the name Val Enson with an illusion called The Aquamarine Girl. Simon Garfield. To the Letter: A Celebration of the Lost Art of Letter Writing, Avery, 2014, p17.

[12] This show, which was shown on 11 October 1980, is on YouTube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Out_OfGDlFg