A FRENCH PREMIERE ON THE LONDON STAGE: ARLEQUIN BALOURD, 1719

By Robert V. Kenny

On 16 February 1719, playgoers at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket witnessed an event which is probably unique in the annals of Anglo-French theatre history: the premiere of a comedy performed, in French, by a company of French actors. The reasons behind this unusual situation deserve to be better known, as does the comedy itself: Arlequin Balourd, by Michel Procope-Couteaux.

The presence of the French actors in London was itself remarkable. Their leader was the actor-manager François Moylin, known as Francisque, who also played the Arlequin of the title.[1] London had seen earlier visits of French performers, particularly dancers and acrobats, and Francisque’s nephew and niece, Francis and Marie Sallé, had been a great success, as ‘the French children’, when they danced at John Rich’s theatre, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, from October 1716 to June 1717. But plays in the French language had not been performed in England since 1684, when a troupe came over at the invitation of Charles II; they, however, performed only for the court.[2] Francisque’s company, more daringly, played on the public stage. Although their repertoire would be readily understood mainly by the élite, they were surprisingly successful.

The Moylin company arrived in London in early November 1718 and opened their season at Lincoln’s Inn on 7 November, giving three performances a week. The season, originally scheduled to end in December, was extended to 5 February. On 12 February the company moved to the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, where they performed for another five weeks. According to the press, the first night in this new venue was ‘By Command, for the diversion of the three young Princesses,’[3] in the presence of the King and ‘a great number of Nobility and Gentry’[4] and a new prologue was spoken by Arlequin and Columbine (Francisque and his wife Marie-Catherine). The first performance of Arlequin Balourd took place on 16 February and the King came to its third performance, which was a benefit for its author.

Procope-Couteaux (1684-1753) was the second youngest of the thirteen children of the Sicilian François Procope-Couteaux[5], the founder in 1684 of the celebrated Paris café Procope opposite the Comédie Française in the rue des Fossés-Saint-Germain (today the rue de l’Ancienne Comédie). He graduated as a doctor from the University of Paris in 1708. Although Procope (as he was frequently called) had a fairly distinguished medical career, ending up as Regent of the Faculty, he was better known for his love of theatres and the convivial company of the actors and writers to be found in his father’s café. By all accounts he was physically unprepossessing, small and swarthy with a hunchback, but he fascinated women with his charming manners and witty conversation.[6] He married twice and he was also rumoured to have had a liaison with a rich Englishwoman. His name was absent from the list of doctors practising in Paris between 1714 and 1724 and it would seem that he spent much if not all of this time in London. It has been suggested that, as a prominent freemason, Procope may have come to London to assist in the setting up of the first Grand Lodge of England in 1717, but this in no way prevented his taking an active part in the busy social and cultural life of the capital. He was sufficiently well known to be referred to in the press in 1720 as ‘a little witty French Physician in this town’.[7]

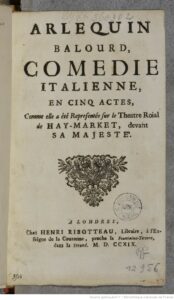

In the preface to the printed edition of Arlequin Balourd, Procope tells how the play came into being. Early in his stay, the fog, the smoke and the dampness of the London air had caused him to fall into a deep depression. He was saved by the arrival of Francisque’s company of French actors and was inspired by Francisque’s performances to write a comedy of his own in the hope of curing his ‘spleen’. As a theatre-lover he would undoubtedly have been familiar with most of Francisque’s repertoire, but one play, Nicolas Barbier’s comedy La Fille à la mode, would almost certainly have been new to him; the play, set in Lyon, had been published and performed there but not in Paris.[8] Even if Procope had somehow come across this play he would not have expected Francisque’s novel version set in London as Le Parisien dupé dans Londres, and he would have been surprised and delighted by the witty and ingenious transferral of Barbier’s original from the banks of the Rhône to the banks of the Thames. The play showed Procope that it was perfectly possible to set a comédie italienne in London, and this is precisely what he did in Arlequin balourd, first performed six weeks after the company’s performance of the Barbier play. The title page of the printed edition reads: ‘Arlequin Balourd / Comédie Italienne en cinq actes, / Comme elle a été representée / Sur le Theatre royal de HAY-MARKET, / devant SA MAJESTÉ.’

Comedie italienne was the form of comedy in French based on the plots and stock characters of the commedia dell’arte as they had evolved in Paris in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries.[9] As the basis for his play, Procope turned to an old, anonymous commedia dell’arte scenario, Li Sdegni (Les Amans brouillés par Arlequin messager balourd), which is summarized in the Dictionnaire des Théâtres:

Flaminia is the ward of the Doctor who intends to marry her. Lelio loves Flaminia, who loves him, but as the Doctor keeps her imprisoned, Lelio uses his servants Scapin and Arlequin to find ways of letting him see his mistress. Arlequin is promised a substantial reward if he succeeds and, being jealous of Scapin’s rival efforts, he devises multiple schemes, carrying them out so clumsily that he causes a row between his master and Flaminia. Arlequin’s blunders create the plot of this play and the marriage of the two lovers is the conclusion.[10]

While it is true that Procope borrowed the bare essentials of Li Sdegni, these essentials, including various lazzi, are in fact common to many of the plays of the commedia; the Doctor and his closely guarded ward, the comic blunders of Arlequin, disguise (Arlequin as astrologer, newspaper seller and Raree Showman), mistaken identity, speaking at cross-purposes, night scenes (Arlequin and Scaramouche rob each other in the dark), etc. From Li Sdegni Procope retained Arlequin’s inability to distinguish left from right, leading to the delivery of letters to the wrong addressees, the promise of a reward for Arlequin — in Li Sdegni a gold chain, in Arlequin balourd a diamond ring — and Arlequin’s catastrophic attempts to outdo his master’s other valet, Scaramouche. In other respects, the play is quite different. It is in five acts, a grande comédie, whereas the Italian comedies were always in three acts. Procope acknowledges in his preface that he benefitted from the advice of Francisque Moylin: ‘I may say, without flattering him, that the least of his qualities is that of being an excellent Arlequin. I talked with him about my play; he inspired me with the desire of seeing it performed, and he even gave me several ideas which contributed not a little to its success.’[11] The result is a minor comic masterpiece with a clever double plot containing many amusing incidents and much witty dialogue, some of it even in garbled English. Rather than coveting his young ward for himself, as in Li Sdegni, the Doctor has promised his niece Isabelle’s hand to his old friend Géronte who has returned from the Indies to marry the girl who is in fact in love with his own son Léandre. (All the principal characters have recently come to London from ‘Les Indes’, quite why, Procope never explains.)[12] Unknown to his father, Léandre too has returned to rescue his beloved Isabelle with the help of his valet Scaramouche and his blundering servant Arlequin. In the cast list Arlequin is described as an ‘Indien’, several years before the more famous wise fool ‘Indien’ of Louis François Delisle de la Drevetière’s comedy Arlequin Sauvage.[13]

But also returning from the Indies is Marinette with her servant Colombine. In the play’s opening scene Marinette reveals that she had been in the service of the elderly Géronte, cynically hoping to profit financially from his early demise. But despairing at his longevity she decided to take her legacy in advance; she stole 4000 guineas’ worth of gold and jewels and fled to London where, masquerading as the Countess Eléanore, she now intends to seduce gullible fools at the theatre and steal the heart of Isabelle’s beloved Léandre. Thanks to Arlequin’s intervention in all the strands of the plot the stage is set for comic disaster.

Encouraged no doubt by Francisque’ example in Le Parisien dupé dans Londres, Procope’s most unusual and highly effective innovation was to set his play in a London which he clearly knew well and seems to have enjoyed. Aspects of London life are exploited throughout the play: places, people, customs and activities, all contribute to make the damp, dangerous and smoky metropolis almost a protagonist, certainly more than mere background. And Procope seems not to have been afraid of shocking or offending his distinguished audience because London is painted, in the words of Oliver Cromwell, ‘warts and all.’ The play contains frequent references to the less salubrious aspects of the life of the city, including the prisons of Newgate and the Roundhouse, the gallows at Tyburn, the notorious Vinegar Yard (later immortalised in Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera), fog, smoke, dirt, pubs, brothels, bath-houses, madams, trollops, pickpockets, stock exchange fraudsters, drinking, swearing, swindling and gambling. Procope notes in his preface that some had accused him of being too satiric and he admits that ‘It is true that in two or three places I spoke of the city of London, but I do not think it a great crime to say that it is smoky and that the streets are not the cleanest.’[14]

In spite of Procope’s disclaimer, references to the negative aspects of London life, and in particular the corrupting power of money, recur throughout the play. Not only has Marinette stolen vast sums but her servant Colombine suggests they should open a gambling den in fashionable Pall Mall or St James’ Street to fleece men not only at the gaming tables but also in private boudoirs. Elsewhere, Arlequin insists that a purse of money is in fact a key to open any London door, and at the end of Act 3 the Doctor’s penniless groom Pierrot tells Scaramouche that his one true mistress is ‘Mademoiselle Guinée’; he longs ‘to find a way to obtain twenty thousand guineas … it’s a pretty thing a guinea, and he who invented them was a clever man; guineas make the world go around, men think of nothing else; as for me, I think about them night and day, because God knows, I love ‘em.’[15] In fact ‘guinea’ is one of the most frequently used words throughout the play.

Two slightly shady London characters add local colour (and English phrases) and contribute to Arlequin’s well-intentioned blunders. A newspaper seller craftily relieves Arlequin of several guineas when selling him the cheap newspapers which Arlequin hopes will gain him entry to the Doctor’s house. A Raree showman (Un Porteur de Curiosités) explains that his large wheeled peep-show cabinet could be used (as in Spain) to smuggle a lover into or out of a well-guarded house, a feat which Arlequin succeeds in performing with, as usual, potentially disastrous results.

But, for all his blunders, Arlequin eventually saves his master from a dreadful fate when he pretends to help a vengeful Marinette, disguised as Isabelle, to marry Léandre in a midnight ceremony. Arlequin foils her plot by disguising himself as his master and marrying her himself. In the inevitable happy ending, Géronte is magnanimous, Léandre and Isabelle are united, Arlequin and Marinette are forgiven and, as Beaumarchais put it many years later, ‘tout finit par des chansons!’ (‘it all ends in song’). Every comedy in Francisque’s London season ended with singing and dancing, accompanied by an orchestra possibly drawn from among the many French instrumentalists working in London. The music for the songs in Procope’s finale may have been composed by Jean-Claude Gilliers (or Gillier) who wrote extensively for the Comédie-Française and the fairground theatres. He also visited London where in 1723 he published a collection of songs, Recueil d’airs Français. Among Francisque’s dancers were Francis and Marie Sallé (aged fourteen and ten respectively), who were to have a profound influence on English dance.

At the first performance of Arlequin balourd an unusual ‘happening’ took place: Léandre appeared on the stage of the King’s Theatre to announce that Arlequin was ill and could not perform. This led to an angry exchange between the actor and a Frenchwoman seated in one of the boxes. The increasingly irate and voluble Frenchwoman finally leaped onto the stage and offered to play the part; it was of course none other than Francisque -Arlequin in drag. Francisque was, as Alexis Piron noted several years later, young, handsome, extremely agile, and could play female roles to perfection. The text of this original and amusing comic routine (probably the basis for much improvisation) appears in the London 1719 edition of the play and it was recorded by two writers some years later. The Abbé Prévost, in his journal Le Pour et Contre and Servandoni d’Hannetaire, in his Observations sur l’art du comédien, mention that Francisque performed the routine in Brussels and London as late as 1733-35. But it seems to have been performed for the first time in London, as a curtain-raiser to Arlequin balourd.[16]

The King’s theatre was usually known as the Opera House, but following the collapse of the opera season under Handel and John Jacob Heidegger, the King’s Theatre had been dark since the beginning of the 1718-19 season. This fact was important for the prologue spoken by Arlequin and Colombine at the company’s opening Haymarket performance on 12 February. The prologue was given again, this time with an epilogue for Arlequin alone, on Monday 16th at the first performance of Arlequin balourd, and both prologue and epilogue, along with Procope’s dedication to the young Princess Anne, were printed in the 1719 London edition, in which Procope-Couteaux thanks ‘Monsieur Vézian’ for having composed both prologue and epilogue. Judging by the prologue’s lavish praise of the House of Hanover, I believe that the author ‘Vézian’ was Anthony Vézian, a member of the large French Huguenot community in London; he was a clerk at the War Office, and an ardent Hanoverian. In 1717 on the anniversary of the accession of George I, along with ‘several French Protestants of both sexes,’ Vézian gave a grand dinner at his house in Paddington, followed by a masquerade ball which went on until dawn ‘in the said Mr Vézian’s house which was finely illuminated.’[17] In 1727 Vézian published a poem in French, mourning the death of George I and celebrating the accession of George II and Queen Caroline.[18]

In the King’s Theatre prologue Vézian, writing for Francisque, makes him comment on contemporary issues. Much is made of the fact that the company is now on the stage of the Opera, home of mythological gods and heroes, and Colombine fears that Arlequin’s naive tricks may not be well received; she mockingly suggests that they should perhaps try to perform opera themselves. This allows Arlequin to launch into a tirade against the boredom of opera, and in support he calls upon the works of Saint-Evremond, who had been famous for his dislike of the genre. Arlequin promises that he will prove to be as capable of tickling the public with novelties as he is of tickling his own dear Colombine. Francisque, now speaking in his own person, sends his wife off to dress, and then delivers an elegant Compliment to the people and their King, who was sitting no more than a few feet away from him: ‘People beloved of heaven, the happiest in the world,/ who enjoy their pleasures in perfect peace,/ Under the rule of a king whose great virtues/ Make him feared and admired to the ends of the earth,/ Happy people of England.’[19]

Apart from the diplomacy and tact of this gesture, Francisque had a personal reason to thank the King who had given him a hundred guineas in November. The Compliment is an excellent example of the political subtlety which seems to have been a hallmark of Francisque’s dealings with his English public. Had Vézian’s piece not been published with Arlequin balourd, we should have known nothing of this unusual text which brings Francisque and his company in from the margins to the very heart of the British courtly and cultural establishment. Lady Margaret Pennyman, writing several years later, recalled being present at this season’s performances and noted that Francisque ‘had been mightily caressed by our English Quality.’[20] Some lines of the prologue, concerning the company’s move to the King’s Theatre, seem to hint at a possible rift between Francisque and John Rich at Lincoln’s Inn Fields: ‘frankly I would have been wrong / Not to have secured entry to this house, / And would to heaven I had done it in the first place.’[21] The last line may suggest that Francisque had originally negotiated with Heidegger for the King’s Theatre and was now returning to him, perhaps regretting his dealings with Rich.[22]

Francisque concluded his Compliment with what amounts to a manifesto. Just as Dr Procope-Couteaux’s preface told how he had been cured of his ‘spleen’ by Francisque, so Francisque now offers a prescription to cure the English nation of their ‘noirs chagrins’. Arlequin-Francisque declares that he intends to return every year with the best Franco-Italian players, bringing much-needed joy to the gloomy natives. It was a bold move in 1719 to diagnose and prescribe a French cure for what George Cheyne in 1733 was to christen ‘The English Malady’ in his book of the same title. The difference in temperament between the lively French and the gloomy English was a serious literary debating point for most of the eighteenth century.[23] It was to haunt Francisque’s London season when he returned in 1734-35; but in 1719 no adverse comment appeared in the press, probably because Francisque had carefully prefaced his remarks on gloom with the fulsome apostrophe to the English and their sovereign.

The King attended the third performance of Arlequin balourd on 24 February (Procope’s Benefit night) and it was for this performance that Vézian added an epilogue in which Arlequin declares that blunderers may be found in every walk of life. The epilogue also sings the praises of Procope, describing him as a small but witty little doctor, much loved by the ladies, whose best medicine is laughter. The fourth and final performance of Arlequin balourd was ‘by His Royal Highness’s Command.’ In 1734, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales had become King George II, and it may have been at the King’s request that Francisque re-staged Arlequin Balourd, advertised as ‘not seen these sixteen years.’ And the return of the play, for four performances, would seem amply to confirm the fact that London audiences cheerfully swallowed the pills of Dr Procope-Couteaux and Francisque Moylin. After these performances, Arlequin balourd disappeared from the stage without trace.[24] However, Francisque had set Procope-Couteaux on the road to becoming a successful minor playwright, and when Procope returned to Paris he wrote for both the Comédie Française and the Comédie Italienne. I hope in the near future to provide a performing edition in English, so that this delightful comedy may once again be appreciated by London audiences.

Robert V Kenny

[1] I use the form ‘Arlequin’ to refer to the speaking character of the Comédie-Italienne as opposed to the silent pantomimic character which evolved (largely thanks to John Rich) on the English stage.

[2] Sybil Rosenfeld, Foreign Theatrical Companies in Great Britain in the 17th and 18th Centuries (London, The Society for Theatre Research Pamphlet Series, no. 4, 1954-5), p.4. Rosenfeld goes on to discuss French visits in the eighteenth century.

[3] The princesses were Anne, Amelia, and Caroline, daughters of George, Prince of Wales.

[4] The Weekly Journal or British Gazeteer, 14 February 1719.

[5] Procopio Cutò, also known as Francesco Procopio Cutò and Francesco Procopio dei Coltelli.

[6] Procope was the butt of many lampoons, in verse by the playwright Alexis Piron and, most notably, by Alain-René Lesage who in his novel Gil Blas mocks Procope as ‘le petit Docteur Cuchillo’ (Spanish for Couteau, or knife) and cruelly describes him as ‘this little runt of the Faculty’ (ce petit avorton de la Faculté).

[7] Anti-theatre, 20 March 1720 (supposedly written by ‘Sir John Falstaffe’).

[8] Nicolas Barbier, La Fille à la Mode (Lyon, 1708).

[9] See R.V. Kenny, ‘The Théâtre Italien in France,’ in Italian culture in northern Europe in the eighteenth century, ed. Shearer West (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

[10] ‘Flaminia est sous la tutelle du Docteur, qui se flatte d’épouser sa pupille. Lélio aime Flaminia et en est aimé, mais comme le Docteur tient Flaminia enfermée, Lélio emploie l’industrie de Scapin et d’Arlequin ses valets, pour parvenir à voir sa maîtresse. Arlequin, flatté d’une récompense considérable, s’il peut réussir dans son entreprise, et de plus jaloux des soins que Scapin prend pour le même sujet, se charge de plusieurs commissions, et les remplit avec tant de maladresse qu’il brouille son maître avec Flaminia. Les balourdises d’Arlequin forment l’intrigue de cette pièce et le mariage des deux amants en forme le dénouement.’ Claude Parfaict and Quentin Godin d’Abguerbe, Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris (7 vols., Paris, 1767; repr., 1967),vol. I, pp. 62-3. The editors knew the London edition and they quote from the Preface the story of the play’s composition.

[11] ‘Je puis dire, sans le flatter, que sa moindre qualité est d’être un excellent Arlequin. Je lui parlay de ma pièce, il m’inspira l’envie de la faire representer, et il m’a donné plusieurs idées qui n’ont pas peu contribué à la réussite.’

[12] ‘Les Indes’ in literature and opera at this time frequently referred to largely imaginary or idealised regions of North and South America rather than any part of Asia. Cf. Rameau’s opéra-ballet Les Indes galantes, 1735.

[13] First performed at the Comédie-Italienne on 21 June 1721.

[14] ‘Ce n’est pas je crois un grand crime, que de dire qu’il y a de la fumée, et que les rues ne sont pas des plus propres.’

[15] ‘trouver le moyen d’avoir vingt mille guinées … c’est une jolie chose qu’une guinée, celui qui l’a inventée avait bien de l’esprit, cela fait remuer tout le monde, on ne songe qu’à cela, pour moi j’y pense nuit et jour, car je l’aime, Dieu sait’.

[16] Jean Nicolas Servandoni d’Hannetaire, Observations sur l’art du comédien (Paris, 1776), pp. 154-5. The anecdote is also recorded by the Abbé Prévost in Le Pour et le contre for 1735, no. 87, p. 287, and repeated by Henri Liebrecht, Histoire du Théâtre Français à Bruxelles au XVIIe et au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1923), p.165.

[17] The Postman, 8 August 1717.

[18] Antoine Vézian, Ode au roi sur son avènement à la couronne, London: Jacob Tonson, 1727. The names of both Procope and Vézian appear in the list of subscribers to the volume of Gillier’s Recueil d’airs Français.

[19] ‘Peuple chéri du Ciel, le plus heureux du monde, / Qui goutez les plaisirs dans une paix profonde,/ Sous l’empire d’un Roi dont les grandes vertus / Le fait craindre, admirer jusqu’aux bouts de la terre, / Heureux Peuple de l’Angleterre.’

[20] Margaret Pennyman, Miscellanies in Prose and Verse by the Honourable Lady Margaret Pennyman, containing her late Journey to Paris (London, 1740), p.42.

[21] ‘franchement j’aurais eu tort /de ne pas de ces lieux m’être assuré l’entrée,/ Et plût au Ciel que l’eussé-je fait d’abord.’

[22] In 1717, Heidegger was reprimanded in the press for planning to bring over a company of French actors.

[23] The intellectual ramifications of the debate are explored by Eric Gidal, ‘Civic Melancholy: English Gloom and French Enlightenment,’ Eighteenth-Century Studies, 37 (1), 2003, pp. 23-45, and Russell Goulbourne, ‘The Comedy of National Character: Images of the English in Early Eighteenth-Century French Comedy,’ Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 33 (3), 2010, pp. 335-55: pp.14-15.

[24] Arlequin balourd was published in London in 1719 by Henri Ribotteau. He was French (and a Huguenot like Vézian), but it may be that some of his typesetters were not fluent French speakers: his edition contains a considerable number of errors of spelling, grammar and punctuation which a native French speaker would not commit. No copy is held by the British Library. Fortunately, there are several copies in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The text of the 1719 edition may be read and downloaded from the Bibliotheque’s website, Gallica: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k855274r.image#. However, the end of the preface and the beginning of the opening scene are missing from this copy.