by David Wood

March 2014,

WSG Productions Ltd:

| Year | Play | Theatre |

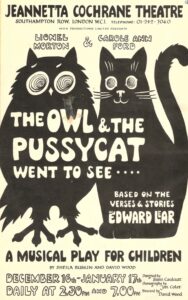

| 1969/70/71 | THE OWL AND THE PUSSYCAT WENT TO SEE…

(including Christmas West End season presented by Knightsbridge Productions Ltd – Apollo Theatre |

Jeannetta Cochrane |

| 1973 | LARRY THE LAMB IN TOYTOWN | Shaw |

| 1978 | FLIBBERTY AND THE PENGUIN | Tour |

Whirligig Theatre

Year |

Play |

Theatre |

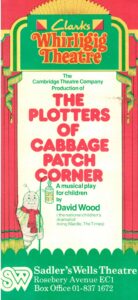

| 1979 | THE PLOTTERS OF CABBAGE PATCH CORNER | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

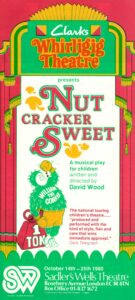

| 1980 | NUTCRACKER SWEET | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

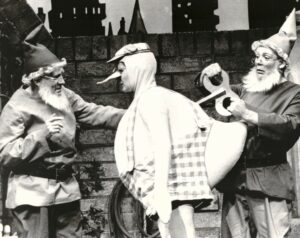

| 1981 | THE IDEAL GNOME EXPEDITION | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1982 | THE OWL AND THE PUSSYCAT WENT TO SEE… | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1983 | THE SELFISH SHELLFISH | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1984 | THE SELFISH SHELLFISH/THE PAPERTOWN PAPERCHASE | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

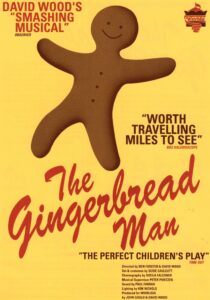

| 1985 | THE GINGERBREAD MAN | Sadler’s Wells/Tour/

Bloomsbury Theatre/ Channel 4 |

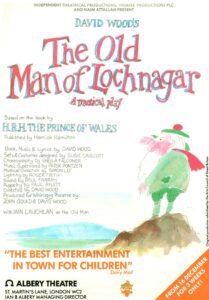

| 1986 | THE OLD MAN OF LOCHNAGAR | Sadler’s Wells/Tour/Albery

Channel 4 |

| 1987 | THE SEE-SAW TREE | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1988 | THE SELFISH SHELLFISH/DINOSAURS AND ALL THAT

RUBBISH |

Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1989 | THE IDEAL GNOME EXPEDITION | Sadler’s Wells/Tour/

Gardner Centre, Brighton |

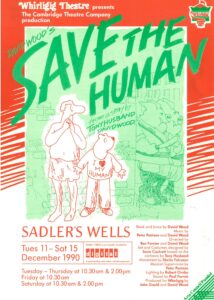

| 1990 | SAVE THE HUMAN | Sadler’s Wells/Tour |

| 1991 | THE GINGERBREAD MAN | Sadler’s Wells/Tour/Corn

Exchange, Cambridge |

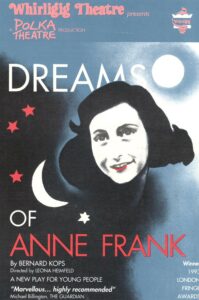

| 1993 | DREAMS OF ANNE FRANK | Tour/Shaw Theatre |

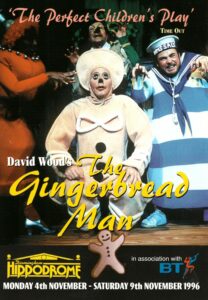

| 1996 | THE GINGERBREAD MAN | Birmingham Hippodrome |

| 1997 | BABE, THE SHEEP-PIG | Tour/Forum Wythenshawe |

| 1999 | THE GINGERBREAD MAN | Troy, New York State |

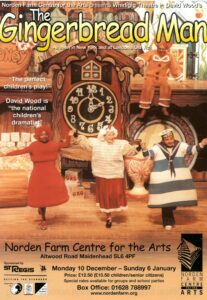

| 2001 | THE GINGERBREAD MAN (25th anniversary production) | Norden Farm Centre for the Arts,Maidenhead |

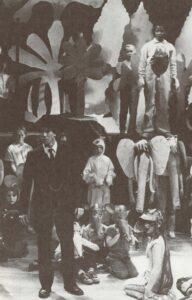

For a play aimed at primary-age children to tour the UK to mainstream theatres, playing daytime matinees for schools and weekend performances for the public, was virtually unknown until Whirligig opened its first production, The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London in the autumn of 1979. Pioneers like Caryl Jenner had toured plays with Unicorn Theatre, but not to the larger or middle-scale venues. Richard Gill’s Polka toured puppets and actors to small theatres and, occasionally the mid-scale theatres like Oxford Playhouse. Theatre In Education had been developing strongly since the 60s and its beginnings at the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry. But TIE was very much intended to work in schools, not theatres. That was the whole point.

For a play aimed at primary-age children to tour the UK to mainstream theatres, playing daytime matinees for schools and weekend performances for the public, was virtually unknown until Whirligig opened its first production, The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London in the autumn of 1979. Pioneers like Caryl Jenner had toured plays with Unicorn Theatre, but not to the larger or middle-scale venues. Richard Gill’s Polka toured puppets and actors to small theatres and, occasionally the mid-scale theatres like Oxford Playhouse. Theatre In Education had been developing strongly since the 60s and its beginnings at the Belgrade Theatre, Coventry. But TIE was very much intended to work in schools, not theatres. That was the whole point.

One of my first professional acting jobs was in the first TIE team based at the Palace Theatre, Watford. This was in 1967. I loved the work, which involved acting several parts in The Tay Bridge Disaster then going into a classroom to discuss the performance and the notion of collective responsibility highlighted in the play. However, I couldn’t help thinking that the theatre experience was as valid, if not more valid, than the theatre-in-school experience. I wanted children to feel the excitement of the lights going down, the music starting, the curtain going up and the theatrical magic that could be created on stage. Many TIE pioneers didn’t feel the same way. I think that to them the idea of ‘the magic of theatre’ was too romantic. They saw theatre as a tool with which to educate. I certainly never disagreed with that, but felt that the two approaches to theatre were valid. One of the problems had been that the mere phrase ‘children’s theatre’ suggested something rather tacky, tinselly or second-rate. This was not entirely fair, in spite of the fact that budgets were often considerably less than those for adult theatre, because the seat prices for children were, rightly, low.

Two things happened to me in that year – 1967 – that helped convince me that theatre for children was an exciting branch of theatre, something I could do reasonably well, and something that I would like to do more of. First, I was asked to act and direct at the newly-formed Worcester Repertory Theatre, based at the Swan Theatre, Worcester. This led to me writing my first children’s play, an adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Tinder Box, which was given its first production for Christmas that year. Second, following my happy experience in the Watford TIE team, I was invited to play in the annual Watford pantomime – Wishee Washee in Aladdin. Directed by Giles Havergal, written by Oxford contemporaries Michael Palin and Terry Jones, with music by another Oxford contemporary, John Gould, the show was not only great fun to be part of, it also gave me the chance to explore the excitement of audience participation, something I knew a bit about, thanks to doing magic at children’s parties, and also organising Saturday morning children’s theatre at Worcester.

The Tinder Box was not a brilliant piece of work, although it was given a faithful, sincere production (I hate the word ‘sincere’, but it best says what I mean), in which there was no overt playing to the adults, over the heads of the children, something which often happened in commercial pantomimes. The story was told honestly, with humour (not tongue-in-the-cheek) and a serious attempt at storytelling. This was in the belief that children love a good through-line story. I never saw the production myself, but it was good enough for John Hole, the theatre director at Worcester, to invite me to write another children’s musical play for the following Christmas. This turned out to be The Owl and the Pussycat went to See…, based on the verses and stories of Edward Lear, co-written with Sheila Ruskin. It was significantly to affect the course of my career. Having witnessed ten performances from the back of the auditorium, and having marvelled at the passion and spontaneity of the audience reaction, I knew this was an exciting branch of the theatre that I must do more of. Indeed, I was determined that The Owl and the Pussycat went to See… didn’t end after its Worcester premiere. A year later, I had managed, thanks to the help of many others, to put it on in a London theatre. It became very successful, was published by Samuel French, then for years afterwards played in most of the regional repertory theatres of the UK.

The London production of Owl was mounted by WSG Productions Ltd. The initials stand for Wood (myself), Scott (Bob Scott, later Sir Bob Scott) and Gould (John, the aforementioned composer/musical director/performer). The three of us had first met in 1964 at Oxford University, where we were involved in a production called Hang Down Your Head and Die, an anti-capital punishment revue, that achieved the unusual feat of transferring from the Oxford Playhouse to the West End. Michael Codron, the celebrated West End producer, was brave enough to bring our undergraduate efforts to the Comedy Theatre. We received great reviews and our six-week season was very successful and, for all of us, I fancy, an amazing experience. I was 20 years old. I had wanted to work in the theatre for almost as long as I could remember. Coming so soon to the West End was a dream come true.

Over the next two years, Bob, John and I worked as a cabaret trio, writing and singing silly songs, at Oxford Balls, cabaret evenings, and even for two seasons in West End night clubs. When final examinations were approaching in 1966, we decided to try our luck at that year’s Edinburgh Festival. John and I had both taken part in Oxford Theatre Group’s productions up there, and now we felt we could go independent. We augmented our trio by recruiting Adele Weston, another Hang Down Your Head and Die cast member, with whom we had done other shows. Her singing abilities tuned in with ours. We were now able to do four-part harmonies, a spoof on a madrigal, for instance, and we were aware that an all-male trio might not work as well on stage in a revue as in a cabaret room. The show was called Four Degrees Over, for obvious reasons, and we managed to get several theatres to book us to play before arriving in Edinburgh. A mini-tour. We started compiling material.

Another excitement in 1966 was the arrival in Oxford of Richard Burton and Elizabeth Taylor, who came to take part in an Oxford University Dramatic Society production of Doctor Faustus. Burton had promised his tutor, Nevill Coghill, when the war ended his studies at Exeter College, that he would return. In the meantime, of course, he had become a huge star and married Elizabeth Taylor. But he was determined to do something for Coghill. It was thought that the proceeds from the Doctor Faustus production would go towards building a studio theatre. Bob Scott was asked to play the Chorus and to understudy Burton. I was invited to play Wagner, Faustus’ servant. My girlfriend at the time (later my first wife, Sheila Ruskin) was Elizabeth Taylor’s understudy. She had also been asked to design Four Degrees Over.

Doctor Faustus was another incredible experience, ending up with a splendid party at the Randolph Hotel. Wood, Scott and Gould were asked to provide the cabaret. Afterwards, talking to the Burtons, who were kind enough to say they had enjoyed our performance, we somehow plucked up the courage to ask them to become Patrons of WSG Productions (not a limited company at this point), so that their names could be on our letterhead and hopefully impress people! At that point I was still booking our tour, writing to theatres and offering them something which was a totally unknown quantity.

The Burtons not only agreed, but also offered to donate £250 towards our enterprise. In those days this was an extremely useful sum of money!

Four Degrees Over became another extraordinary experience for all of us. We had good reviews on tour, and very early on, Michael Codron, who had transferred Hang Down Your Head and Die, offered to do the same for Four Degrees Over. He suggested some changes to the show, to which we agreed. He found us a director (up until then, we had directed ourselves), John Cox, who became a celebrated opera director. He asked us which West End theatre we would like to play in! We immediately replied that the Fortune would be perfect. For us it meant Flanders and Swan, Wait A Minim and, most of all, Beyond the Fringe, shows which we all had admired hugely. Although we certainly didn’t become a cult success, Four Degrees Over played at the Fortune for a couple of months. We even had a cast album produced by the legendary Beatles’ producer, George Martin.

Bob, John and I now had to make our individual ways in the big, bad world … But WSG Productions still existed, and in 1967, John and I produced and performed in another touring revue called Three to One On. Again, we went to the Edinburgh Festival. No West End transfer, however, but a ‘special’ on BBC2 television.

Over the next few years, WSG became a limited company and put on several productions, all of them home grown. John performed a one man show, featuring his humour at the piano. He wrote a lovely musical revue based on John Betjeman’s poems called Betjemania, which we toured and produced in London. Another version of John’s one man show, Bars of Gould, was heard on Radio 4, and played at the Mayfair Theatre in London, co-produced by Bill Kenwright.

Meanwhile, we were all doing our own things as well. I was acting. Bob was becoming a theatre administrator, notably in Manchester at the 69 Theatre Company, which later became the Royal Exchange. Adele had become a teacher, and later started writing very successfully for children.

The success of The Owl and the Pussycat went to See… in 1968 made me determined, as I wrote earlier, to get the show on in London. WSG Productions seemed the ideal vehicle, if we could find the money. Luckily, both John and Bob were very willing to let our partnership go in a slightly different direction. Friends, including Michael Palin, put small sums of money into the pot. We secured the Jeannetta Cochrane Theatre, in Southampton Row, off Kingsway, a theatre that was the perfect size and was not officially regarded as a West End theatre which would have been far more expensive. Because the budget was tight, we found it difficult to find a director. Those we approached either wanted more money than we could pay or were put off by the knowledge that this was a children’s play. Having by now directed a couple of plays at Worcester, I offered my services. So, for the first time, I directed a children’s play. Again, this was something that changed the course of my career, really. I found I enjoyed doing it. It seemed that I could do it reasonably well. I didn’t need to be paid, should the budget be too stretched. Bob introduced me to Susie Caulcutt, a new theatre designer, who did a wonderful job on the set and costumes. Malcolm Sircom, the musical director who had worked on the show’s premiere at Worcester, and done the musical arrangements, was the musical director, playing the piano. There was certainly no money for any other musicians. And we found a choreographer called Jan Colet, who proved to be a great team member, not only arranging the dances, but also spending his spare time painting bong leaves for the set and helping to paint the Jumblies’ boots pink!

We were lucky enough to get two ‘names’ in the cast. Carole Ann Ford played Pussycat. She had been Dr Who’s first assistant in the iconic television programme. Lionel Morton, who played Owl, had not only been in a successful pop group, The Four Pennies, but was also a regular presenter of BBC tv’s Play School.

We opened happily, having had only two weeks to rehearse. I had previously spent hours going through telephone directories, hand-writing envelopes in which to send publicity material to London primary schools. The set was built too cheaply, and its main circular raked disc structure had to be taken apart and rebuilt, using screws instead of nails … but somehow the show went on and got a wonderful review in the Evening News. The box office phone became hotter and hotter and the elderly lady in the box office – the only employee in the box office – became overstretched. I helped out, as did the director of the theatre, Mick Orr. The production, which only played for three or four weeks, broke even, enabling us to repeat the experiment the following year (Christmas 1970).

For Christmas 1971, the West End impresario Eddie Kulukundis took WSG’s production of Owl into the West End, to the Apollo Theatre. Eddie had employed me twice as an actor – in David Mercer’s After Haggerty, which he transferred from its Royal Shakespeare Company Aldwych Theatre home to the Criterion, and in Alan Ayckbourn’s Me Times Me, at the Phoenix, Leicester and on tour. Eddie kindly came to see Owl at the Jeannetta Cochrane Theatre, loved it and offered to bring it into town in association with WSG. Not only that, he was interested in my new play, The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, which had opened at the Swan Theatre, Worcester for Christmas 1970. So, along with Owl at the Apollo, Eddie put Plotters into the brand new Shaw Theatre on the Euston Road. It played there for two Christmas seasons. Julia McKenzie played Ladybird the first year. The production was directed by Jonathan Lynn, who had never directed a children’s play before. He later established himself as the co-writer of the brilliant tv series, Yes, Minister, and went to direct movies in Hollywood. We had already employed him on a couple of grown-up WSG shows, directing a revival of our revue Four Degrees Over and also John Gould’s one-man show. Jonathan proved to be the perfect children’s play director, because he never patronised the audience. He treated the play as seriously as if it were an Ibsen! Plotters received great reviews. Susie designed the stunning set and costumes.

Owl didn’t play Christmas 1972, but we brought it back to the Jeannetta Cochrane Theatre for Easter, 1973, when, sadly, part of the ceiling fell in during an early performance. There could have been fatalities, but, by a miracle, the four unoccupied seats took the main impact. We transferred to the Collegiate (later the Bloomsbury) Theatre, and managed to recoup our subsequent losses from the local council, who owned the Jeannetta Cochrane Theatre, which remained closed for a couple of years.

Also in 1973 David Wright, who was one of the National Youth Theatre management team, got in touch. The NYT were the tenants of the Shaw Theatre, in the Euston Road, which had opened two years previously. John Gould and I had known David since our Oxford days, when he co-devised Hang Down Your Head and Die, the anti-capital punishment revue which had transferred from the Oxford Playhouse to the West End in 1964. David said that they had been pleased with The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, which had played the previous two Christmas seasons. He wondered if I had anything else to offer for Christmas 1973. I suggested Larry the Lamb in Toytown, the adaptation by Sheila Ruskin and myself that had originally been commissioned by the Swan Theatre, Worcester in 1969. As a highly successful radio programme in the 50s, and also as a television animation series in the 60s, Larry the Lamb and his friends were very well-known characters. Sheila and I had persuaded Hendrik Baker, an ex-stage manager who had worked with Larry the Lamb’s creator, S.G. Hulme-Beaman, and was in charge of all the rights, to let us create a stage play. The Worcester production had gone down well. David and the Shaw management liked the idea. I discussed with John the possibility of WSG Productions Ltd. presenting the play, and set about trying to find enough money to put it on. The Shaw’s producing company, a kind of professional arm of the National Youth Theatre, was called the Dolphin Theatre Company. They became our co-producers, giving us the use of the theatre and help with publicity. But we needed several thousand pounds investment. Our Jeannetta Cochrane theatre productions of The Owl and the Pussycat went to See… had been artistically well received, but had not made money.

Fate offered a friendly hand. In the summer of 1973 I was acting in The Provk’d Wife at Greenwich Theatre. In the cast was Linda Thorson, who had found fame as Tara King in The Avengers, the extremely popular television series. One night, waiting in the wings for the opening of the play, I told Linda about our Larry the Lamb plans and hopes. She happened to be the partner of Laurie Marsh, a very successful businessman, who had owned all the Classic cinemas, and was involved in West End theatre ownership and production, with partners such as Ray Cooney and Brian Rix. Linda kindly organised a meeting, and Laurie, even more kindly, came up with the necessary funding. Larry the Lamb in Toytown, with lovely, colourful, faithful-to-the-original, sets and costumes designed by Susie Caulcutt and with musical direction by Peter Pontzen, and directed by myself, was well received. Melody Kaye, a future Whirligig stalwart, played Larry, Veronica Clifford – who later created the role of The Old Bag in my play The Gingerbread Man, played Mrs Goose and Geoffrey Lumsden, a sporting, elderly old-school actor, played the Mayor. The Mayor’s Clerk and the Baby Dragon were played by Ian Judge, who later became a successful opera director. Ian hated wearing his beautiful but hot and head-covering Dragon costume, but the audience absolutely adored him. Unfortunately the business at the box office was very disappointing, and even more unfortunately, the generous Laurie Marsh lost all of his investment…

Round about this time I met Cameron Mackintosh. He introduced himself to me at a party celebrating the opening of the Noel Coward bar at the Phoenix Theatre. He said that he loved The Owl and the Pussycat went to See…, and had visited several regional productions. If there were any chance, he said, of working on that show with you, I would be honoured! Cameron, at that time, was in the early stages of his brilliant career, touring plays on a shoe string. We did indeed work together on Owl, putting it on at the Yvonne Arnaud Theatre, Guildford for a Christmas season, then asking another director, John David, to do a production at the Gardner Centre, Brighton. This later toured and came into the Westminster Theatre, London.

WSG had been happy for me to progress this new alliance with Cameron. We certainly didn’t feel that WSG could take on a tour at this point. We were all quite busy on other things.

Cameron and I also produced Owl at the Towngate Theatre, Basildon, a small theatre in Essex. It was very well received.

So, the following year, 1976, the Towngate commissioned me to write a new play. I managed to get the Theatre Royal, Norwich to commission it in return for the touring rights for one year. The play turned out to be The Gingerbread Man. Cameron came to see it at Basildon and offered to co-produce it with me in London the following Christmas. We opened for Christmas 1977 at the Old Vic, where we received great reviews and were invited back for Christmas the following year. Eventually, the play became my biggest success, playing in London for many Christmas seasons, and touring many times. It also took off internationally, particularly in Germany. Indeed, WSG Productions occasionally produced The Gingerbread Man – exactly the same production! – without Cameron’s involvement. Similarly, Unicorn Theatre produced it a couple of times – again, the same production!

The Gingerbread Man was directed by the Plotters director, Jonathan Lynn. He did a wonderful job. He eventually directed it three times, but then had no further time to devote to it, so I took over. Really, I reproduced his production, occasionally tweaking it or cutting the odd line, but basically it stayed the same for many years – indeed, the 25th anniversary performances at Norden Farm Theatre, Maidenhead, used exactly the same set – not just the same design, the same physical set, which still looked great and worked well. It was designed, as have most of my children’s plays been, by Susie Caulcutt.

In 1997, the Towngate, Basildon asked for another production for Christmas. I suggested Flibberty and the Penguin, the play I had written for the Swan Theatre, Worcester in 1971. The Towngate produced it themselves. Little did I realise this production would later become the pilot production for Whirligig Theatre …

So, by 1978, several of my plays had been performed in various venues, and had toured a certain amount. Cameron and I had toured The Owl and the Pussycat went to See… and a tour of The Gingerbread Man was on its way. But there was still very much the feeling that my plays were achieving success for just a few weeks each Christmas-time, and that a year in the life of a child is a long time! It seemed crazy not to give people all over the UK the chance to bring their children to see the shows locally. Touring was the answer. But it was not a simple thing to organise. I was well aware of the fact that it was financially incredibly difficult to make ends meet, particularly if the plays were of the scale I wanted – most of them had a cast of ten or twelve. Not only that, many of the theatres were not interested in a show that played mainly daytime performances. They insisted, if they were to take a children’s show, that it should fit on top of an evening attraction. Our sets tended to be quite large, and very tricky to fit on top of another set. There was, too, an attitude amongst theatre managers that simply didn’t view children’s theatre as particularly important, necessary or commercially viable. So I knew that my dream of touring quality children’s theatre to major theatres was not something that could easily be fulfilled. I recognised that sponsorship or subsidy would be essential. Sponsorship was almost a dirty word in Arts Council circles in those days. Arts sponsorship was in its infancy. And there was very little money available from the Arts Council for children’s theatre. I don’t think the Touring Department had ever subsidised a children’s tour.

So it was, in 1978, that John Gould and I met in the Hand in Hand pub on Wimbledon Common to discuss whether or not we could find a way forward to establish a touring children’s theatre company, to perform in major venues, targeting primary school audiences on weekdays and family audiences at weekends.

We agreed that we should aim to work towards establishing a touring company, by planning a pilot tour in the autumn of 1978. We decided that Flibberty and the Penguin would be a reasonable choice of play. I still had the physical production stored in my garage. The Basildon production, which I had directed, had been well received. Also, it had attracted a strong cast, including three television names. Brian Cant, the Play School legend, George Layton, actor/writer (Doctor in the House) and John Cater, currently recognisable from the series The Duchess of Duke Street. Flibberty had first played at the Swan, Worcester – the fifth annual commission from John Hole. The play was about a Penguin who had lost his parents. Flibberty, a kindly goblin/pixie/elf character, helps him. The play is really a quest that ends up at the zoo, with the happy reunion of the Penguin family. I saw it as a kind of Feydeau farce, full of mistaken identities. Mr Maestro, a famous orchestral conductor, wearing a tailcoat, gets mistaken for the penguin. There is also confusion because another kind of conductor, a bus conductor, is also a major character. Added to this, Mr Maestro, being so musical, cannot understand you if you speak to him – you have to sing to him. A villainous Krafty Kingfisher is in pursuit, and a comedy policeman adds to the mayhem. There are also two Silly Cuckoos, vying with each other to become the first cuckoo of spring. Looking back, it was really quite a complex plot! Susie Caulcutt had designed a lovely set and some beautiful costumes.

As WSG, we managed to get a short tour with most of the theatres paying a guarantee that would contribute a guaranteed sum to the costs. The Arts Council, to our surprise I think, gave us a small but welcome subsidy. And the Alfred Beck Centre, a newly-opened venue in Hillingdon, Middlesex, invited us to do a Christmas season. Roger Edwards, who ran the theatre, needed a name to sell the show. I remember checking the availabilities of many children’s television presenters and other well-known actors, and eventually securing the services of Johnny Ball to play the Bus Conductor. Johnny was very well known on children’s television, and just had a few weeks’ availability. He definitely helped box office sales. The tour and the Christmas season were well enough received to make us determined to press forward with our plans to establish a regular touring company.

The tour had opened at the Civic Theatre, Darlington, thanks to the Theatre Director Peter Tod. Over the years, Peter became very important in Whirligig’s story. At Darlington and later at the Bristol Hippodrome, he regularly invited us to open our productions or visit on tour, giving us a decent guarantee to cover the costs. His commitment to our aims – to reach as many primary school children as possible – led him to offer the seats at low prices. The business was tremendous, even if the box office take was not enormous, compared with adult productions. Peter never minded this. He saw regional theatre as a service to the community. Children were part of that community and deserved their own special productions. Peter became a great ally.

The other theatres we played were not the grandest or the biggest, but all enthusiastically received us. The Thameside Grays, Theatre Royal Newcastle, Palace Theatre Newark, the Rex Wilmslow all took quite a risk with us, bearing in mind that, in those days, few theatres had marketing departments, and the notion of doing direct mailing to schools was in its infancy.

It must have been in June 1978 that Jacqui, my wife, and I were on holiday in Menorca. English newspapers were expensive, so we restricted ourselves to a Sunday paper, which had lots of sections and supplements. Some of these we would not normally have read but, in the circumstances, each section was given a serious look. Jacqui discovered an article about a man called Bill Kallaway, who had set up an arts sponsorship business. He seemed to be a pioneer, trying to put together artistic ventures and commercial companies willing to give sponsorship, not necessarily as philanthropy, but as a business proposition.

When we returned home, I got in touch with Bill Kallaway, who invited me to a meeting. He seemed sympathetic to WSG’s ideas and asked for some more detailed, written plans. He said he would then do his best to find us some sponsorship for a possible tour. He felt that we needed a name for the company. Very quickly I came up with ‘Whirligig Theatre’, partly because there had been a television programme in my childhood called Whirligig, which had been a great favourite, and also because the word suggested ‘going round’, which was exactly what touring meant.

To our surprise and delight, Bill Kallaway delivered! It wasn’t long before he told us that Clarks Shoes were interested to support us. It seemed – and, indeed, proved to be – an ideal match. Clarks were well known for caring about children’s feet. There would be nothing controversial about them supporting us. It would have been impossible, for instance, to have a sweet manufacturer or a cigarette company sponsoring us. John Gould and I met various representatives of Clarks and plans were made to launch the company with a tour of The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, opening on October 9th, 1979, at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London.

1979

We were extremely fortunate to secure Sadler’s Wells, a prestigious London theatre, particularly noted for its dance programme. Historically, it is often linked to the Old Vic, because the remarkable Lilian Baylis made it her life’s work to programme both theatres with culture for a mass audience both north and south of the river Thames.

Derek Westlake was running Sadler’s Wells at the time. I like to think he was sympathetic to this new children’s theatre company and its work, rather than just filling a vacant slot! I’m sure his heart was in the right place, however, because he offered us two weeks of daytime performances, without insisting we play on top of an evening show. On Saturday we did two public performances, but, again, not an evening show. He also offered us two weeks, which we had not expected, but which helped establish us by giving audiences and critics a bit more time to come and assess our work. It was notoriously hard to tempt the critics to review a children’s production. But Plotters certainly succeeded.

Derek’s faith in us was bolstered by his decision to invite us back the following year. And Sadler’s Wells subsequently became Whirligig’s London ‘home’. This was a great help to us. A regular London date helped us get publicity. It also was an attraction to actors, who were more likely to join the company when they knew they had a London showcase. Furthermore, we were, as the years went by, able to announce a Whirligig season months ahead, so that schools could pencil in their requirements and, once they trusted us, make Whirligig a regular school trip.

We chose Plotters for our launch, partly because there was already a physical production, but also because its two London Christmas seasons at the Shaw Theatre, in 1971 and 1972 had been very well reviewed.

Furthermore, Jonathan Lynn, who had directed the two London seasons of Plotters, had by now been appointed Artistic Director of the Cambridge Theatre Company. I had been delighted when he announced that he wanted to produce The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner at the Arts, Cambridge. Now it seemed sensible for Whirligig Theatre to present the Cambridge Theatre Company production of the play. Jonathan agreed.

The play had originally been commissioned by the Swan Theatre, Worcester, where it played the 1970 Christmas season. When I had asked Jonathan to direct the 1971 production, he had employed as choreographer, Sheila Falconer, who had done a splendid job. Sheila focussed more on movement for actors than full choreography, with the result that the insect characters came vividly to life, all moving in their own idiosyncratic way. Sheila, who had previously worked as Gillian Lynne’s assistant, became an invaluable member of our Whirligig team. She was involved in every show we created, over the full 25 years the company existed. Because Jonathan was otherwise engaged, it was decided that Sheila should direct Plotters, and she did so brilliantly.

Susie Caulcutt’s set and costumes were refurbished and looked as good as new. In the cast were several actors who became Whirligig regulars. Melody Kaye, who had played the Penguin in Flibberty and the Penguin the year before, returned to play Maggot. Mike Elles was a slimy Slug, and Lucy Fenwick played Ladybird.

Another vital ingredient in the Whirligig mix was Peter Pontzen, the musical supervisor. Like Sheila Falconer and Susie Caulcutt, Peter was involved with every Whirligig production. He first came into my life in 1970, when I went to see a repertory production of The Owl and The Pussycat went to See… at the Crewe Theatre. It may have been called the Lyceum, then. Ted Craig, the Artistic Director, had both directed the play and played – rather well – the Turkey. After the show he invited me to meet the cast. I asked immediately if I could meet the musical director too. Peter had played the piano for the show exactly as I had always imagined the music should be played. I told him this, and asked for his contact details, in the hope that we could work together at some point.

The following Christmas (1971), Owl was playing in London, and Plotters was coming to the Shaw. We needed an extra Musical Director, so Peter was appointed. He was brilliant. He then worked regularly on my productions, and, having worked for Whirligig from day one, also stayed for the duration. He also became my musical supervisor, doing the musical arrangements of all my songs for virtually all my musical plays. He was an indispensable member of the team.

Two other dedicated company members were Chris Stringer and Kevin Chadderton. Chris had already worked for WSG Productions as a Production Manager and as a Company Manager. Kevin’s first production with us, as Deputy Stage Manager (on the book) was Plotters. He stayed as DSM, until promoted to Company Manager, for the next 25 years.

Clarks made sure that they supported us with more than financial subsidy. They provided – in their company colours – all our printed publicity, as well as a beautifully produced free cut-out toy theatre of Plotters, plus a free programme for every child, comprising a comic-strip telling of the story. These giveaways were the beginnings of our responsible attitude towards schools. Although we didn’t want to be seen as an overtly ‘educational’ company, nevertheless we wanted teachers to see how our plays could trigger the children’s imagination. We may not have been doing plays that related directly to what subsequently became known as the National Curriculum, but we wanted teachers to use the theatre experience to encourage children to write or to draw pictures or to act out scenes from our plays. So we began preparing Teachers’ Packs, something that was unusual in those days for a touring theatre production as opposed to a TIE tour into schools. We also organised Teachers’ Seminars, at which we would talk about the play, show the designs, discuss ways in which the teachers might instigate follow-up work, and generally make them feel that we were providing theatrical entertainment as a genuine introduction to theatre for children, rather than as a purely commercial exercise. At Sadler’s Wells, we made a point of inviting the teachers to enter the theatre via the Stage Door and take the service lift to one of the ballet rehearsal rooms, in which celebrated ballerinas like Margot Fonteyn had practised. Hopefully the teachers enjoyed feeling part of our adventure. Certainly we used to get a good attendance, until, as the schools began to trust us more and more, fewer teachers would come, yet box office numbers would increase.

The tour of Plotters visited more theatres than the Flibberty pilot. We played at the Gordon Craig Stevenage, the Grand Wolverhampton, the Poole Arts Centre, Darlington Civic, Sunderland Empire, Newark Palace, Theatre Royal Hull, then opened for a Christmas season at the Hexagon, Reading. I think we were their first ever Christmas production, the theatre having only recently opened.

It might be worth saying at this point that Whirligig Theatre never occupied an office. John Gould worked from his home in Wimbledon, then Brighton, as I did. By now I had been fortunate enough to employ a part-time secretary/assistant. Barbara Shipton worked on Whirligig’s behalf as well, half her salary being paid by the company. John, having trained for several years as a chartered accountant, coped admirably with the finances, including budgets and the company’s wages. I did the publicity blurbs and press releases. Somehow we managed to keep everything going in this somewhat makeshift manner. In later years, we shared the workload with Barry Sheppard, whom we were delighted to welcome as Administrator, when his contract running the Oxford Playhouse was terminated, and the theatre temporarily closed. Barry had been a great supporter of Whirligig, booking us into the Oxford Playhouse regularly. We always did excellent business there. Barry started working for Whirligig in 1988; until then, John and I, helped by Barbara, ran the company as efficiently as we could. Indeed, it may be argued that having so few cooks actually contributed to our efficiency – Stephen Remington, who ran Sadler’s Wells for several years, told us we were the most efficient company he dealt with …

Sadler’s Wells was an exciting place to be. But, in all honesty, it wasn’t the easiest theatre for children’s theatre. The auditorium was large and between it and the stage was an enormous orchestra pit. Whirligig budgets never stretched to more than one musician, so the pianist/keyboard player would sit all alone, sometimes boxed in by a black forestage covering the rest of the pit. In fact this large gap between the stage and the audience felt worse for the actors than for the spectators, because the sightlines in both the stalls and the circle were cleverly designed to ‘lose’ the orchestra pit when sitting. But, without microphones or sound enhancement of any kind, it was a tribute to the cast that they could be heard throughout the theatre. And the volume and passion of the audience participation must have taken the Sadler’s Wells resident crew by surprise. We had been somewhat concerned that they might have resented the arrival of a children’s show in a venue used to high-class ballet and opera. Indeed, on the morning before the technical rehearsal, I listened in to a conversation over the headphones as I sat at the production desk. An electrician was expressing somewhat disparaging remarks about our ‘kiddies’ show’. It was truly rewarding when, in the pub next door at our post-opening gathering, the same technician went out of his way to say how exciting and electrifying he found our performances, because of the incredible gut reaction and uncynical enthusiasm of the audience. It’s probably true to say that Sadler’s Wells had never before witnessed audiences of primary school parties. Over the years we came to treasure our Sadler’s Wells weeks, when we proudly displayed our wares to London.

One heartstopping memory from Whirligig’s first production came alarmingly early in the run. I think it was the second performance, a morning schools’ performance, which we knew several national newspaper critics would be attending. When the actors arrived for their warm-up, one was missing. Red Admiral, one of the insects in the play hadn’t turned up. By the end of the warm-up and the announcement of ‘the half’ (thirty-five minutes before curtain up) there was still no sign. And there was no answer from the telephone number he had left with the company manager. After another ten minutes we made the decision that the understudy would have to go on. Robin Kermode had had no rehearsal. As assistant stage manager he had spent much of the rehearsal time gathering props. But, in this emergency, it is to his eternal credit that he put on the costume for the first time, showed that he had learnt the lines and been making notes of his entrances, moves and exits, and was, to boot, a real trouper. He got through the play with considerable style. The reviews next day were positive. Thank you, Robin. The real Red Admiral eventually arrived, mortified, having overslept. It didn’t happen again …

1980

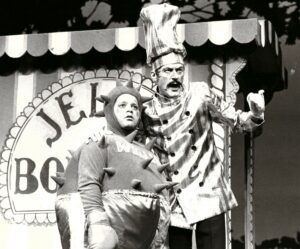

We were pleased to be invited back to Sadler’s Wells the following year, 1980. Clarks Shoes agreed to stay on board, having been pleased with the inaugural Plotters tour. So we planned another tour. The play chosen was Nutcracker Sweet, which had originally been commissioned by David Horlock, Artistic Director of the Redgrave Theatre, Farnham in 1977. David had been at school with me – Chichester High School – and we had both been members of the Chichester Youth Theatre. We both went to Oxford, too, although he was a year ahead of me. After Oxford he had become an associate director at Bristol Old Vic, where he had directed two of my plays – The Owl and The Pussycat went to See… and The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner. Now he was running his own theatre at Farnham, and kindly commissioned a new play for children. The plot involved a cast of nut characters, who were part of a Nutty May Fair. They were in danger from Professor Jelly Bon Bon, a high-class confectioner in search of choice nuts to cover with chocolate for his latest assortment. The life and death situation for the nuts grabbed the imagination of the young audience, particularly when, having been thwarted, the Professor turned his attention on the audience, threatening them with the fate of becoming Chocolate Children. David had cleverly directed the play at Farnham, but I wasn’t entirely happy with it. Samuel French had offered to publish it, but I asked them to wait until we had secured another production. A Whirligig tour was the perfect way of giving the play another chance, and I took the opportunity of directing it. The regular creative team returned. Susie designed it, Sheila choreographed, and Peter was the musical supervisor. Melody Kaye, Mike Elles and Lucy Fenwick, all of whom had been in Plotters, returned as Hazelnut, Kernel Walnut and Gypsy Brazil. A welcome new recruit was Caroline High as Old Ma Coconut. Caroline was married to Kevin Chadderton, who returned as DSM. Chris Stringer was the Company Manager and Production Manager once more.

The Chocolate Squirter, as Professor Jelly Bon Bon became affectionately known, was played by a very tall actor, Richard Bremmer, who succeeded in causing some of the most passionate audience participation I have ever witnessed. The children loathed him and all he stood for, and when he got his comeuppance at the end – he himself was squirted by his own chocolate-squirting machine and became a giant piece of confectionery – they raised the roof with joy.

Clarks again provided the publicity, as well as sponsorship, plus an attractive giveaway to every child, comprising a series of finger puppets of the characters and interesting information about the nuts and where, in the real world, they came from. The newspaper critics were enthusiastic and teachers appeared to approve of the play, even though it was not overtly educational. Over the years it has been difficult to predict what teachers really want. Sometimes they look for a play that covers some aspect of the National Curriculum, other times they are happy to give the children a treat. Whirligig’s philosophy was always to make the plays entertaining, but to incorporate, with integrity, a problem or moral dilemma that the children would find interesting, using characters and situations that would appeal. This often, of course, involved fantasy and/or anthropomorphism, but, as we developed as a company and as, I think, I developed as a writer, we later turned to environmental themes, which offered teachers more contemporary material to follow up in the classroom.

Clarks gave us £36,000 towards the Nutcracker Sweet tour. We aimed to embark upon a longer tour – 20 weeks. Our guarantees for box office shares were budgeted at an average of £4,000 a week. This meant there was a potential shortfall of £24,000, for which we applied to Arts Council Touring.

It is worth recording here that throughout our 25 year history, the Arts Council regularly refused to make us revenue clients, which would have meant that we could plan ahead, in the knowledge that we would automatically be receiving subsidy the following year. We were always on ‘project grants’, which often meant we didn’t have confirmation of the grant or the amount until very late in the day. Often we had committed to theatres and already spent money on publicity print before knowing we could go ahead. And, as will be explained later, a couple of times we came unstuck and had to withdraw from a tour, because we simply didn’t have enough guaranteed funds.

For Nutcracker Sweet, eventually Arts Council Touring gave us £14,000, less than we needed. But, somehow, thanks to John Gould’s financial skills, we managed to scrape through without a deficit.

We opened at the Ashcroft Theatre, Croydon in August 1980, and toured through to January 1981. Our list of theatres was improving in quality. Some theatres invited us back, following reasonable business the previous year. And Sadler’s Wells continued their support by again booking us for two weeks. After Croydon we played the Arts Cambridge, the Palace Newark, the Key Peterborough, the Alhambra Bradford, the John Player Theatre in Dublin (two weeks, as part of the International Theatre Festival), two weeks at Sadler’s Wells, the Adam Smith Centre Kirkcaldy, the Theatre Royal Glasgow, the Civic Darlington, Bristol Hippodrome (to which Peter Tod had now moved from Darlington), New Theatre Cardiff, New Theatre Hull, Gordon Craig Stevenage, Oxford Playhouse, Buxton Opera House and the University of Warwick Arts Centre, where we played two weeks. This was to become the beginning of a fruitful relationship – in future years we often opened our productions at Warwick.

In November we learned, with great pleasure, that the Clarks sponsorship of Whirligig had won a coveted ABSA Award, as a top example of successful business sponsorship. It was a happy coincidence that we played Bristol Hippodrome round about that time, because Clarks had their offices and factory at nearby Street in Somerset. After the Saturday matinee performance, to which all the Clarks employees had been invited, we arranged a splendid tea party in the Circle Bar. It was an opportunity to say thank you to Clarks, but also for them to witness our work, and hopefully encourage them to stay with us!

1981

In 1981 it was agreed that we would tour Chish ‘n’ Fips. This was a play I had been commissioned to write for the 1980 Christmas season at the Liverpool Playhouse. William Gaunt, the Artistic Director, had generously given me a very open brief, except that ideally the cast should not exceed six. The play I came up with involved two garden gnomes, who, bored with their backyard existence, decide to go on an adventure into the concrete jungle of the big city. The subject matter offered nice opportunities to explore the dangers of urban life, including the difficulty of crossing roads. Road safety was a useful publicity tool when advertising to school parties. But I was careful to make sure that, in the audience participation, it was the audience who knew more than the innocent Gnomes, and, helped by Chips, the streetwise cat, taught the gnomes how to get across the road safely. This was less patronising than simply teaching the audience how to stay safe.

The play had been well received in Liverpool, but I was worried about the title. For some reason I had come up with the title long before thinking of what the play might be about! Bill Gaunt liked it, and started advertising the show before we had much clue about its content. As it turned out, there was indeed a character called Chips, but there was nothing that really related to Chish ‘n’ Fips… For days I struggled to come up with a better title, knowing that our publicity deadlines for the Whirligig tour were approaching. On the final day, I happened to see in the newspaper a reference to The Ideal Home Exhibition. Instantaneously, I excitedly thought of The Ideal Gnome Exhibition and seconds later revised it to The Ideal Gnome Expedition.

(It is worth recording that a few years later I wrote a television series based on the play. This time we reverted to the title Chish ‘n’ Fips, and justified it by setting the gnomes’ home in the back yard of a fish and chip shop.)

The usual team returned – Susie, Sheila and Peter – and, returning for a second year was Paul Knight, a musical director who gave excellent service to Whirligig for several years. Mike Elles and Melody Kaye returned in the cast, and Keith Varnier, who had several times by now played Sleek the Mouse in The Gingerbread Man for Cameron Mackintosh and myself, joined the company to play Chips, the cat. There was a character called Wacker, who was a tar-whacking machine (when writing the play for Liverpool, I was delighted to find that the trade name of such a machine was indeed Wacker, which, of course, is also the Scouse (Liverpool) word for ‘mate’ or ‘friend’. In the original Liverpool production, this role, as well as the role of Securidog, a fierce animal guarding an adventure playground, was played by Daniel Webb, who, as Danny Webb, later became very well known in adult theatre. In our touring production, we were lucky enough to employ – in his first role, I think – the splendid Clive Mantle.

For the first time, we rehearsed in the church hall of St Mary, Newington, in Kennington – a hall that was to be our rehearsal home for many years.

The sets were impressive and extremely large! They almost symbolised our wish to be providing substantial theatre productions rather than Theatre In Education tours, in which the cast and the set would tour together in one van. We almost over-compensated. Another reason, of course, was that my play used scale as its main ingredient. The gnomes, played by human-sized actors, had to have ‘giant’ backgrounds to act against. So a pavement with a gutter became a considerable hurdle – and a large piece of scenery. And just as there was a giant flowerpot in The Plotters of Cabbage Patch Corner, in The Ideal Gnome Expedition, there was a giant dustbin. Clarks Shoes came in with £18,000 plus an extra – special – £2,000 to help us introduce theatre to the Gaumont Cinema, Doncaster.

After considerable negotiation, Arts Council Touring gave us £18,000, and South Eastern Arts gave us £750 towards our Eastbourne date.

We opened at University of Warwick Arts Centre, then played Bristol Hippodrome, Gordon Craig Stevenage, Towngate Theatre Basildon, New Theatre Hull, Civic Darlington, Buxton Opera House, Adam Smith Centre Kirkcaldy and the Oxford Playhouse. Then we managed to secure a short Christmas season at the Gardner Centre, Brighton.

Clarks provided us with give-away badges for every child. Encouraged by Clarks, we organised a competition for children, asking them to imagine that they were one foot high – Gnome’s Eye View.

1982

In 1982 we prepared our fourth annual tour. In spite of the fact that the tour was shorter – twelve weeks, we were more than grateful for support from Clarks (£22,000) and from Arts Council Touring, who surprised us a little by offering us a guarantee against loss of £38,000. The total budget was nearly £140,000, not an insignificant sum.

Looking back, this was one of the most straightforward of Whirligig’s touring years. Our net box office receipts ended up at just over £131,000. Whirligig, of course, only took a share of these receipts, but, with the sponsorship and subsidy, it was possible to make the figures work.

Having said that, we hadn’t felt confident enough to embark on a brand new production. We chose The Owl and The Pussycat went to See… written by myself and Sheila Ruskin, first produced at the Swan Theatre, Worcester in 1967. Since then, the play had become popular amongst the regional repertory companies. Based on the verses and stories of Edward Lear, it offered entertainment value, plus, for the schools, interesting follow-up possibilities using Lear’s classic rhymes and characters. Following earlier tours by Cameron Mackintosh and myself, there was a reasonable physical production in existence. It needed quite a bit of refurbishment and not all the costumes were still usable, but the money we saved enabled us to employ a larger company than the previous year. The cast of twelve included regulars Melody Kaye and Lucy Fenwick, plus the return of Stephen Reynolds, who had been in Flibberty and the Penguin for WSG and Allan Stirland, who played the Plum Pudding Flea for the umpteenth time since the first London production of the play in 1969. Newcomers Malcolm Ward and Jane Arden were excellent as the Owl and the Pussycat. Wenda Holland, who later became a successful theatrical agent, Shaun McKenna, who went on to write the spectacular Lord of the Rings musical, and Tim Bannerman, who had, the previous year, been in the cast of Meg and Mog Show, my show produced by Unicorn Theatre. John Dallimore, Richard Sockett and David Goodwin completed the excellent cast. The two understudy/ASMs were Gary Raynsford and Sally Cookson, both having just graduated from LAMDA. Sally later became an extremely successful deviser and director of children’s productions. In those days, actors had to be members of Equity in order to join a company. But most touring companies and repertory companies could take on two acting ASMs, who could automatically apply for membership of the union. With Gary and Sally, we had a tussle with Equity and the Theatrical Management Association, which centred round whether or not we were a number one touring company. We were deemed NOT to be, but compromise was reached when we agreed that Sally and Gary would not understudy principal roles, only secondary ones. I remember we were displeased that, because we played to children, we were not given number one touring company status, even though we were playing many number one touring theatres.

Susie, Sheila and Peter all returned as the creative team. I directed again. Lighting was by Bill Bray, the resident lighting technician at Chichester Festival Theatre, who had lit the play when it played a Christmas season there. He did an excellent job, although I think he was taken by surprise at how speedily he had to supervise the lighting rig and design his cues. By then, we had got used to the fact that we would usually get-in to our first venue on the Sunday, do technical and dress rehearsals on the Monday, and open on the Tuesday morning.

We used several different lighting designers over the years. Steve Kemp, a splendid ally, had lit Plotters and Ideal Gnome. He died tragically young. Later, Roger Frith, the incomparable Robert Ornbo and others took on the tricky task of making our shows look beautiful, using an uncomplicated rig which could be reproduced in all the other venues.

Everybody working for Whirligig, in whatever capacity, was employed on a fee per production basis. In twenty-five years, we never had one full-time employee.

The Musical Director was Simon Lowe and Paul Farrah was the Sound Designer. Paul was, at the time, developing his lighting and sound hire company. He designed the sound for many of our future productions. Carrie Bayliss had by now become our splendid Wardrobe Supervisor, whose job it was to find the skilful makers to create Susie’s remarkable fantasy costumes.

Chris Stringer (Company Manager) and Kevin Chadderton (DSM) were still with us, fighting our corner when necessary, against some theatre crews who saw children’s theatre as ‘easy’ or less important that grown-up theatre. They often got a big shock when the pantechnicon arrived, revealing a set at least as large as that for a middle-scale musical.

There was sometimes the problem, too, of fitting us on top of an evening attraction. This was always extremely difficult. At Birmingham Hippodrome, it had been agreed that The Owl and The Pussycat went to See… would play on top of a dance show called Dash. Meetings had taken place between the two companies to establish how they could fit on top of one another. We knew it would be tricky, but certainly not impossible. Dash opened first. We were expected to get-in overnight. There were angry scenes when Dash refused to remove parts of their set. At about two o’clock in the morning Chris Stringer rang me to say that it might be impossible to open the show as advertised, because an impasse had been reached. I had to ring Richard Johnston, who ran the Hippodrome, wake him up and ask him to go to the theatre and arbitrate. He did, and eventually we opened Owl on time.

(Another example of the ‘sharing problem’ manifested itself in our very first year – 1979. For at least three months we had been contracted to play Plotters at the Grand, Wolverhampton. We had signed a clause agreeing to share with an evening attraction. However, when the Grand announced we would be sharing with a touring production of The Beggars’ Opera, we discovered that their set was so big and complicated, it would be impossible for us to share. Even though we had signed our contract months before the grown-up company, we were advised that it would be foolish to appeal the decision of the theatre to drop Plotters. Luckily, even though it was very late in the day, we were able to secure a week at Liverpool instead. Then Wolverhampton offered us just five performances in the week before their pantomime opened. So all resolved itself reasonably happily.)

Owl got great reviews and did good business virtually everywhere. We played the Civic Darlington, Sunderland Empire, Sadler’s Wells, Bristol Hippodrome, Theatre Royal Plymouth, Gordon Craig Stevenage, Theatre Royal Glasgow, Buxton Opera House, Birmingham Hippodrome, New Theatre Hull, Grand Theatre Swansea and the Oxford Playhouse. At our regular theatres, box offices reported increased business from year to year. Now, other major theatres were coming on board the whirligig.

The total paid admissions for the Owl tour were 84,865, a very respectable number. We reckoned to aim to play to 100,000 children a year, and managed to achieve that figure many times. Percentage-wise, our best theatre was, as it had been before, the Oxford Playhouse, where we did 98% business over ten performances, representing in excess of 6,000 admissions. Barry Sheppard, who ran the Playhouse, took the credit for this great result. Little did John Gould and I realise how important Barry would become in the Whirligig story …

1983

By now, our publicity contained the phrase ‘An Arts Council Tour’. We were happy to be supported by them, even though we knew their subsidy might not last. In 1983, we were forced to ask them for extra help, because, early in the year, we heard that Clarks were unable to sponsor us again. They had financial problems, involving factory closures. They apologised profusely. However, in fairness, the fact that they had remained with us for four years was pretty remarkable.

Ruth Marks, who was the Touring Officer at the Arts Council had been sympathetic to Whirligig and its unique aims. We wrote to her in March, 1983 asking if Arts Council Touring could support us on their own. We knew that it was unlikely that we could find another sponsor for that year, even though attempts would be made to find a successor in 1984.

In May we learned to our relief, and with much gratitude, that £45,000 had been approved. But Arts Council Touring wanted a reduction for the Sadler’s Wells week, which did not come under their remit. We had managed to reduce the budget by a further £13,000, by reducing the cast by one and cutting back on some of the set. Eventually we scraped through! By this time Jodi Myers was also working in the Arts Council Touring department. She became important in our story in later years.

The play we chose was The Selfish Shellfish. This was the first overtly environmental play I had written. Set in a rock pool, featuring a cast of shellfish characters, the play had first been commissioned by Stephen Barry, the Artistic Director of the Redgrave Theatre, Farnham, where the play was first performed in March, 1983. Stephen directed it himself, very well, and we got some lovely reviews. It felt right to put on a Whirligig production only a few months later, and we decided to bring in the usual team – Susie, Sheila and Peter to create a new production, which I directed.

The play we chose was The Selfish Shellfish. This was the first overtly environmental play I had written. Set in a rock pool, featuring a cast of shellfish characters, the play had first been commissioned by Stephen Barry, the Artistic Director of the Redgrave Theatre, Farnham, where the play was first performed in March, 1983. Stephen directed it himself, very well, and we got some lovely reviews. It felt right to put on a Whirligig production only a few months later, and we decided to bring in the usual team – Susie, Sheila and Peter to create a new production, which I directed.

For the first time we employed a Casting Director, the excellent Sheila McIntosh, who introduced us to several actors we might have ‘missed’ without her expertise. Melody Kaye, Caroline High and Richard Sockett returned to us, and David Learner (Seagull), Bernard Finch (H.C) and Bill Ritchie (The Great Slick) were newcomers. An excellent new find was the Assistant Stage Manager, David Bale, who also played the part of Sludge. David became a Whirligig regular in years to come. Bill Bray returned to do the lighting. Paul Farrar came back to do the sound. Paul Knight returned as Musical Director. What was really encouraging was how many of our personnel seemed to enjoy coming back for more!

Although I had been considering a more meaty subject than usual, something with a significant moral dilemma, with which to challenge our young audience, I was not really intending to create a play that combined the elements of children’s theatre and those of Theatre In Education. But I suppose that is what I was doing. But I certainly didn’t want to let the tail wag the dog – I felt it was wrong for teachers and educationalists to set the agenda for the content of a children’s play. Indeed, I had been approached by a teacher trying to persuade me to do a play about water, because it was on the curriculum. This was not what I wanted to do. I wanted to give the children a theatrical experience that was not necessarily directly linked to their education syllabus.

Strangely, the idea for The Selfish Shellfish did not come from a desire to explain to children the dreadful effects of oil spillage and pollution. For some reason I suddenly had a vision of an actor wearing a cloak, so big that it would cover the entire stage. This theatrical image was very appealing, and I tried to imagine what character might be thus portrayed. An oil slick seemed to be an interesting thought. This led to the creation of the play, in which The Great Slick comes to invade the rock pool and thereby kill all its inhabitants. The audience had fun creating a storm with which to frighten off the monstrous Slick. I was aware that this was not a real possibility, rather a theatrical fantasy solution to a problem, but reckoned that it was enough to sow the seeds of the oil pollution problem in the minds of our young audience, who would not take literally the possibility that pretending to be a storm could affect the power of Mother Nature …

We opened successfully at the Civic, Darlington and then played the New Theatre Cardiff, Festival Theatre Paignton, Empire Theatre Liverpool, Towngate Theatre Basildon, Palace Theatre Manchester, Buxton Opera House, Sadler’s Wells, New Theatre Hull, Alexandra Theatre Birmingham, Bristol Hippodrome and the Oxford Playhouse.

1984

There was quite a lot of interest in The Selfish Shellfish, enough to make us consider the idea of touring, for the first time, in the Spring of the following year. We reckoned that with a few reasonable guarantees, we could make another tour of up to ten weeks just about pay for itself, especially if we received a small subsidy from Arts Council Touring. In the end, we requested just £5,000.

For the second tour, as well as the first, we organised as much schools liaison as was possible. Eileen Oliver was employed to do the work, as well as to sell relevant merchandise in the foyer. The theme song of The Selfish Shellfish was called When Will We Learn? and became popular with schools. It also, for a time, became the anthem of Friends of the Earth. We sold copies of the sheet music plus a 45 rpm record.

For this tour, Lucy Fenwick took over the role of Starfish and Wenda Holland returned to the company as Urchin. Ian Cross played Seagull and Colin Wakefield played The Great Slick. Colin was to return to Whirligig later that year, before going on to write extremely successful pantomimes. Our rehearsals were helped by the fact that we could use the set, which was erected on the stage of the Questors Theatre, Ealing.

A particular pleasure for me was taking the play to Chichester Festival Theatre, where I had been an extra in the second season in 1963. I had been at school in Chichester and my old English master, who was a considerable influence, was the secretary of the Friends of the Festival Theatre. It was a real pleasure to make contact with him again, and also Geoffrey Marwood, one of the two masters at school who had directed me in several school plays.

The Spring tour, 1984, of The Selfish Shellfish opened at the University of Warwick Arts Centre, then played Chichester Festival Theatre, Theatre Royal Bath, Theatre Royal Glasgow, Kings Theatre Edinburgh, Palace Theatre Newark, Richmond Theatre, Theatre Royal Brighton, Grand Theatre Swansea and the Grand Theatre Leeds. The quality of this list of number one theatres (or, at least, most of them) shows how Whirligig’s credibility had increased, and how more mainstream theatres were willing to introduce children’s theatre to their programming. Interestingly, Clarks Shoes very kindly gave us £3,000 towards our week in Bath, which was not far from their offices and factory in Street, Somerset. We enjoyed working with them again. American Express gave us £750 towards our week in Brighton. But finding a new major sponsor for Whirligig was becoming problematic. Our relationship with Clarks had been headline news. Other sponsors were reluctant to work with us, because they felt that the word ‘Whirligig’ was almost indelibly linked to Clarks Shoes.

The Spring tour lost nearly £1,000, but we were delighted that, following the loss of Clarks support, we had managed to keep going.

One thing that helped us balance the books was the fact that I was writing and directing the plays, and could always waive my royalties, when they were needed to subsidise the production. This became a regular happening, which I never resented because the touring success of the company was more important to me, and also because some my plays were beginning to be recognised and performed by other companies, both professional and amateur, which helped pay the rent!

For the Autumn 1984 tour, we wanted to do a somewhat larger production than The Selfish Shellfish, mainly because we were now playing in more theatres seating 1,000 or more. The play I suggested, and John agreed to, was The Papertown Paperchase, the play I had originally written as the 1972 Christmas production at the Swan Theatre, Worcester. Samuel French had published the play, but I had always had my doubts about its structure. The story follows a struggle between the Land of Fire and the paper citizens of Papertown. There is a Beauty and the Beast element, in which a young Salamander, who has failed his fire-breathing test, kidnaps young Tissue. Fireman Silver (made of silver paper that does not burn) leads the quest to rescue Tissue, accompanied by a kind of comedy double-act, Carbon and Blotch. Having seen the original production, I felt that the action went backwards and forwards between the two lands too many times. And there were several scenes that were too wordy. But I was confident that it was possible to re-work the play for a Whirligig production, and, as I was directing it too, I felt I could build on the success of the initial production. It proved an ambitious choice. A large cast, many costumes, several sets, including moving trucks. But it proved to be one of our most spectacular shows, beautifully lit by Bill Bray, and one that yielded a tremendous response and passionate audience participation.

Colin Wakefield, David Bale, Shaun McKenna and Mike Elles returned to the acting team, along with three new talented female recruits, Sophia Winter (who later worked for Alan Ayckbourn and at the National Theatre before tragically dying of an ectopic pregnancy), Jane Whittenshaw (later a very successful radio actress) and Shannon Sales.

The Salamander was really a ‘skin’ role, needing excellent mime skills. Paul Aylett did a splendid job. His main career as a puppeteer had been effectively employed the previous year, when he designed the amazing, long-armed Great Slick. Susie, Sheila and Peter all returned and did their usual excellent work. Chris and Kevin were again our Company and Stage Manager. Carrie Bayliss once again supervised the wardrobe. The touring wardrobe mistress was the highly efficient Kathy Butterly, fresh from a stint on Les Misérables. The two ASMs, who both were in their first jobs and acquiring their Equity cards via Whirligig were Lisa Bowerman, who later combined her acting with a very successful photographic career, and Howard Leader, who went on to considerable success as one of Esther Rantzen’s reporters on the television programme That’s Life.

Funding this year proved problematic. Arts Council Touring offered us a £40,000 guarantee against loss, which was less than we had asked, but still positive. Sponsorship, however, proved virtually impossible. We had a regretful letter from Malcolm Cotton, the Managing Director of Clarks mid-August, saying they couldn’t help at all. Remarkably, a couple of weeks later, they generously offered us £2,500 towards our week at the Bristol Hippodrome. We gratefully accepted. BP Chemicals responded positively to one of our many letters appealing for sponsorship, but disappointingly only offered £25. Bill Kallaway tried hard, but failed to achieve a major sponsorship. Again, it seemed that Whirligig’s name was linked so closely to Clarks that potential sponsors were put off.

Somehow John managed to balance the books, against all the odds.

In spite of the fact that we had no sponsor to provide a giveaway for every child, we managed to produce a free programme, which incorporated a board game based on the play. And, for the teachers, we provided Project Fire, an interesting bundle of documents for schools’ use, produced by the Home Office. We had realised that, as one of the themes of the play was fire, we could promote the educational value of learning about the dangers of fire, fire prevention etc. Eileen Oliver returned to look after schools’ liaison.

The Papertown Paperchase played for eleven weeks. We opened at the Civic Darlington, and then played the Empire Liverpool, Gordon Craig Stevenage, Bristol Hippodrome, Sadler’s Wells, New Theatre Hull, Buxton Opera House, Birmingham Hippodrome, Theatre Royal Nottingham, Grand Theatre Swansea and the Oxford Playhouse.

1985

For the Autumn tour, 1985, we thought that Meg and Mog Show might be a good idea. My adaptation of the Meg and Mog books had been first produced by Unicorn Theatre in 1981, and had been revived successfully. We thought that we could keep our production costs down by touring this production, which had never been seen outside London.

However, this was not to be. We still had major problems with sponsorship.

The Arts Council eventually came up with £42,000, which helped considerably. But we needed to find enough guarantees from a dozen theatres to ensure we could break even.

Because of this, we decided to offer The Gingerbread Man. Since the first production of my play in 1976, at the Towngate Theatre, Basildon, Cameron Mackintosh and I had produced it twice at the Old Vic and subsequently toured it a couple of times. But the play had not been seen in the regions for some years and theatres were keen to book it, and to give a reasonable guarantee. This meant that our need for sponsorship was, if not removed, certainly lessened. Thanks to Laurence Harbottle, our solicitor, we received £500 from St James Productions, but nothing else.

Susie and Peter returned, having both worked on The Gingerbread Man before, and Sheila Falconer choreographed it for the first time (not the last!). Robert West, Cameron Mackintosh’s legendary Company Manager, had also worked on The Gingerbread Man before, and very effectively lit the production for us.

Mike Elles and David Bale returned to the acting company, along with new faces Susannah Bray (who was to become a regular), Philip Eason, Pepsi Maycock and Colin Hurley, who later did great work at Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre. Stuart Pedlar joined us as Musical Director.

We played Theatre Royal Newcastle, Civic Darlington, University of Warwick Arts Centre, Sadler’s Wells, Kings Theatre Edinburgh, His Majesty’s Theatre Aberdeen, New Theatre Hull, Grand Theatre Swansea, Birmingham Hippodrome, Palace Theatre Newark, Buxton Opera House, Grand Opera House Belfast and the Oxford Playhouse.

Jodi Myers had taken over from Ruth Marks at Arts Council Touring. She became a sympathetic supporter.

The Gingerbread Man was then offered a London Christmas season at the Bloomsbury Theatre, which we felt able to take on, because the tour was virtually guaranteed to break even. The London season was successful, and led to Channel 4, the television channel, commissioning a television production of our stage production, which was recorded in a studio, complete with live audience, and screened at Christmas 1986.

Net box office receipts for The Gingerbread Man tour and Christmas season exceeded £140,000. Our share did indeed cover the costs of the tour.

Every child in the audience received a free programme, containing a board game based on the play.

Although The Gingerbread Man was a ‘smaller’ show than Whirligig’s usual productions, the set – an antique Welsh dresser on a giant scale – seemed to fill the stage wherever we played. This always intrigued me, because it was exactly the same set, not just the same design, the same physical set we had originally used at the Towngate, Basildon, which had a very small stage. The same set seemed to work absolutely fine in the large theatres, which was a considerable relief. It also meant that in years to come, whenever there was a financial problem for Whirligig – and, indeed, Unicorn Theatre – The Gingerbread Man would ride to the rescue!

1986

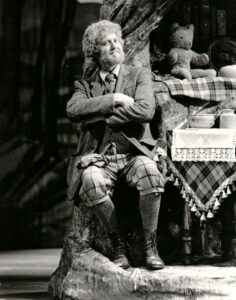

1986 proved to be a rather special Whirligig year, although it was also fraught with difficulty! Over a period of about 2 years I had tried to secure the stage rights of The Old Man of Lochnagar, the children’s book written by HRH The Prince of Wales. This involved meetings with the Prince’s Private Secretary at Buckingham Palace, although I never met the Prince himself. Having provided a synopsis, the Palace informed me that I must write the play and submit it, before any rights could be given or plans made for a production.

I delivered the play, which I felt was faithful to the book, although it developed considerably the characters and created a more theatrical and, in some ways, logical plot. Prince Charles had clearly been influenced by his favourite radio characters, The Goons. This led to the creation of some delightful characters, including the Gorms (from the Cairngorms) and Lagopus Scoticus, a Scottish Loch equivalent of the Old Man of the Sea. The somewhat anarchic events that affect the Old Man of the title are somewhat episodic, so I needed to create a through storyline.

The extraordinary Peggy Ramsay, who was my agent, although Tom Erhardt did most of the work on my behalf, agreed to read the play, just in case it needed to be changed before being delivered to the Palace. She phoned me and said that she felt the second half was better than the first. She also said that I probably ought to remove the lavatory … when I pointed out that the Old Man’s special lavatory, that could be flushed by pulling on one of the pipes of a set of bagpipes, was featured heavily in the book, Peggy immediately cried, ‘Oh well, that’s fine, dear!’ and put the phone down.

The play was accepted without any requests for re-writes. To this day I have no idea whether Prince Charles actually read it. He certainly never came to see it, nor did any members of his family. This was a shame, partly because I would have liked him to see it, but also because we never benefited from the publicity a visit from him would have brought us. We had gone to the trouble of opening the production at His Majesty’s. Aberdeen, the nearest theatre to Balmoral, where we knew the Royal Family would be staying for the summer holidays. The local press became very excited and forced one of their photographers to virtually camp on the front steps of the theatre, just in case HRH suddenly arrived. Perhaps the newspaper only had one photographer, because they didn’t cover the photo call we organised – their man and his camera were resolutely standing by outside …