News

7 October 2019 / Blogs

Navigating the Archive

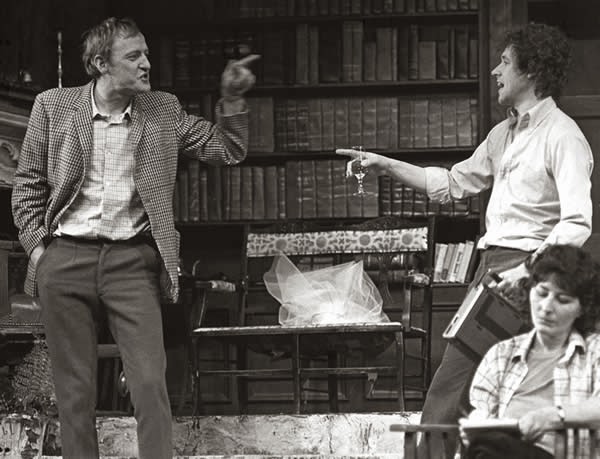

image: Niall O’Brien, Stephen Rea and Kate Flynn in Aristocrats by Brian Friel in 1979

Dr Barry Houlihan of NUI Galway won a Research Award in 2018 to complete the production of Navigating Ireland’s Theatre Archive: Theory, Practice, Performance. This has now been published and will be launched at the upcoming symposium in Galway on October 24th on Performance and the Archive – full details of this here.

These essays cast light on the persistence and reliability of memory, and the ‘potential of the archive’ to unlock unexpected aspects of the development of theatre and its reflection of society . He writes:

These essays cast light on the persistence and reliability of memory, and the ‘potential of the archive’ to unlock unexpected aspects of the development of theatre and its reflection of society . He writes:

“The Inconsistent Stage”: Addressing Our Performance Memory

The British critic and essayist, William Hazlitt, in the early eighteenth century, questioned the need and the rationale for documenting and remembering theatre and the craft of actors. In his influential essay, On Actors and Acting, Hazlitt outlines how “players are the ‘abstracts and brief chronicles of the time’; the motley representatives of human nature”. Hazlitt continues to question:

It has been considered as the misfortune of first-rate talents for the stage that they leave no record behind them except for vague rumour, and that the genius of a great actor perishes with him, “leaving the world no copy”. This is a misfortune, or at least a mortifying reflection to actors; but it is, perhaps, an advantage to the stage. It leaves an opening to originality. The semper varium et mutabile of the poet may be transferred to the stage, “the inconsistent stage”, without losing the original felicity of the application.

(46-47, William Hazlitt: Essays, The Gresham Publishing Co. Ltd. London, [18–])

Hazlitt’s words still carry great resonance today but they also have an updated urgency as the ‘inconsistent stage’ today has multiple forms. The interface of the stage between performer and audience is no longer always ‘the fourth wall’ but often rather the screen or device you consume the performance through, the location you arrive at, the (inconsistent) memories you take away after the performance has ended. The performance consists of a multitude of media and can continue into the online fora and social media platforms through which you discuss and share your thoughts after the performance has ended.

In my new volume of essays, Navigating Ireland’s Theatre Archive: Theory, Practice, Performance, I titled the introduction, “The Potential of the Archive”. Libraries, archives, museums, galleries and institutions the world over have been and are collecting and documenting the labour and experience of both theatre-making and theatre-going. The book puts forward arguments that are built on the idea of navigation: how does one journey through the archive? Where does that journey begin and where does the historical record provide a definitive end-point – if it ever does so? Perhaps most importantly, what are the modes of questioning with which we interrogate the archive, as well as the digital record of performance itself?

It also sets out to assess where the ‘potential of the archive’ can lead us in the future? In a sense, the archive of performance today is less about reaffirming our knowledge in what we do know, but more about uncovering what we didn’t look for before. Also, it enables a reading of our theatrical history and repertoire that was not always possible. In 2016, a women-led movement of theatre-makers emerged to respond to a paucity of opportunity and engagement for women artists at the Abbey, the National Theatre of Ireland. It awoke, not just a reflection on employment and work practices across the Irish theatre section, but also about the status of the archive and repertoire itself – where are women recorded in the archive? Is their work produced on minor fringe stages or on national platforms? Are records also sought out from theatre-makers from immigrant backgrounds, for example? The archivist community needs to actively pre-empt and intervene in the live documentation of our respective national dramas. Institutional selectivity is the acquisition and/or appraisal of collections need to assessed regularly to prevent a narrow tunnel-vision version of our theatre histories. The documented evidence is ever little more than effigy, detritus of past transaction and interaction. But its latent power lays in its potential to affect change, knowledge and accountability.

Individual chapters within the collection also look at how terms around what defines ‘British’ theatre, ‘Irish’ Theatre, or ‘Northern Irish’ theatre, and their respective repertoires, terms which are perhaps less clear today. In Ireland in 2016, the major theatre event was DruidShakespeare a marathon production of Richard II, Henry IV (Parts 1 & 2 ), and Henry V – into one composite drama played out over six hours. 2016 was also the 400th anniversary of the death of William Shakespeare. 2015 was the 150th anniversary of the death of William Butler Yeats, Nobel-prize winning poet and co-founder of Ireland’s national Theatre, The Abbey. Yet, no major professional production (or even a staged reading) of a Yeats play was produced at the Abbey in 2015.

In recent years British theatres have staged many productions of classic Irish plays or new plays by British playwrights with an Irish theme. Brian Friel’s Aristocrats was staged at the Donmar Warehouse, for example, while Friel’s arguably most important play, Translations was produced in the National Theatre, London, also in May 2018. Enda Walsh’s opera/drama The Second Violinist was produced at the Barbican in October of that year, while Jez Butterworth’s The Ferryman provoked a divided reaction among critics and public for its alleged Irish stereotypes. It is hard to neatly fit any of these works easily into the bracket of being ‘an Irish play’. All plays are essentially of universal experience, of communication, language and grief.

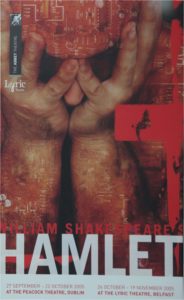

In Navigating Ireland’s Theatre Archive, Emer McHugh examines the pedestal of commemoration and how ascribed commemorative norms prescribe certain opinions, such as Shakespeare considered as ‘an English playwright in Ireland’. McHugh uncovers Irish theatre’s relationship with this most ‘English’ of playwrights, and how the repertoire of Irish theatre remembers or dis-remembers his plays within the gamut of its turbulent Anglo-Irish political and social context. Moreover, McHugh suggests that these archival materials tell us about cultural attitudes towards Shakespeare in modern and contemporary Ireland. Conor O’Malley draws on a personal memoir and archive to recount the birth of a new theatre in Belfast, Northern Ireland, that blossomed from amateur to professional while all the while being in the ominous shadow of the cloud of conflict during ‘The Troubles’. Founded by Mary O’Malley in 1954, the Lyric [Players] Theatre afforded communities in Northern Ireland an outlet from which to escape political and sectarian divide and be part of a cultural movement. The theatre inevitably fell within the crosshairs of conflict from internal and external pressures. The archive of memory acts a powerful and necessary restitutive agent for communities that are still engaging with a post-conflict legacy and adds context to world of Butterworth’s The Ferryman.

In Navigating Ireland’s Theatre Archive, Emer McHugh examines the pedestal of commemoration and how ascribed commemorative norms prescribe certain opinions, such as Shakespeare considered as ‘an English playwright in Ireland’. McHugh uncovers Irish theatre’s relationship with this most ‘English’ of playwrights, and how the repertoire of Irish theatre remembers or dis-remembers his plays within the gamut of its turbulent Anglo-Irish political and social context. Moreover, McHugh suggests that these archival materials tell us about cultural attitudes towards Shakespeare in modern and contemporary Ireland. Conor O’Malley draws on a personal memoir and archive to recount the birth of a new theatre in Belfast, Northern Ireland, that blossomed from amateur to professional while all the while being in the ominous shadow of the cloud of conflict during ‘The Troubles’. Founded by Mary O’Malley in 1954, the Lyric [Players] Theatre afforded communities in Northern Ireland an outlet from which to escape political and sectarian divide and be part of a cultural movement. The theatre inevitably fell within the crosshairs of conflict from internal and external pressures. The archive of memory acts a powerful and necessary restitutive agent for communities that are still engaging with a post-conflict legacy and adds context to world of Butterworth’s The Ferryman.

Music journalist David Hepworth recounts how his own memory cast doubt over his recollections of when he first saw the musician David Bowie perform on television. To solve the problem, Hepworth turned to the online video sharing platform, YouTube:

I went to YouTube just now to see if the memory I’ve kept in my head for more than forty- three years is correct. When David Bowie appeared on Top of the Pops on 6 July 1972 performing ‘Starman’, did he really point at the camera on the line: ‘I had to phone someone so I picked on you- hoo- oo’? He did. In the glory days of Top of the Pops you couldn’t watch things again. You retained them in the archive of your memory. People watched hungrily, believing it would be their only chance.

This ‘personal archive of memory’ as mentioned by Hepworth, is undergoing continual reinterpretation and reconstitution. Turning to unstable web-based outlets such as YouTube as ‘reliable’ repositories is inconsistent for the practice of historiographic scholarship. The future premise is one that must embrace technological and born-digital content and enhancement, entering the new territory of web archives, ‘big data’ analytics and manipulation of vast interconnected datasets. Hazlitt’s manifesto for documenting performance is not with the plan to create a blueprint for future actors and artists to recreate. Instead the creative space within the margins, the questions and gaps can instead inspire future theatre makers into their own original work, rather than hinder their processes within a constrictive tradition, a ‘mimesis of mimesis’. Archiving of future performance will not aim to fix ‘the inconsistent stage’ but perhaps to make our memory more consistent.

Navigating Ireland’s Theatre Archive: Theory, Practice, Performance edited by Dr. Barry Houlihan is now published by Peter Lang Press, Oxford. https://www.peterlang.com/view/title/63197 and was the recipient of a publishing grant award from the Society for Theatre Research.