News

12 November 2019 / Grants and Awards

Genghis Khan on the Elizabethan stage

Elizabeth Tavares received a Research Award in 2018 for her research into Tartars and Mongols in Elizabethan drama. Here she gives us an overview of her work.

Elizabeth Tavares received a Research Award in 2018 for her research into Tartars and Mongols in Elizabethan drama. Here she gives us an overview of her work.

Chinggis Khan in the Elizabethan Archives

Ottomanus, Sophye, Turke, and the great Cham:

Robin goodfellowe, Hobgoblin, the deuill and his dam.

— Fedele and Fortunio (1585)

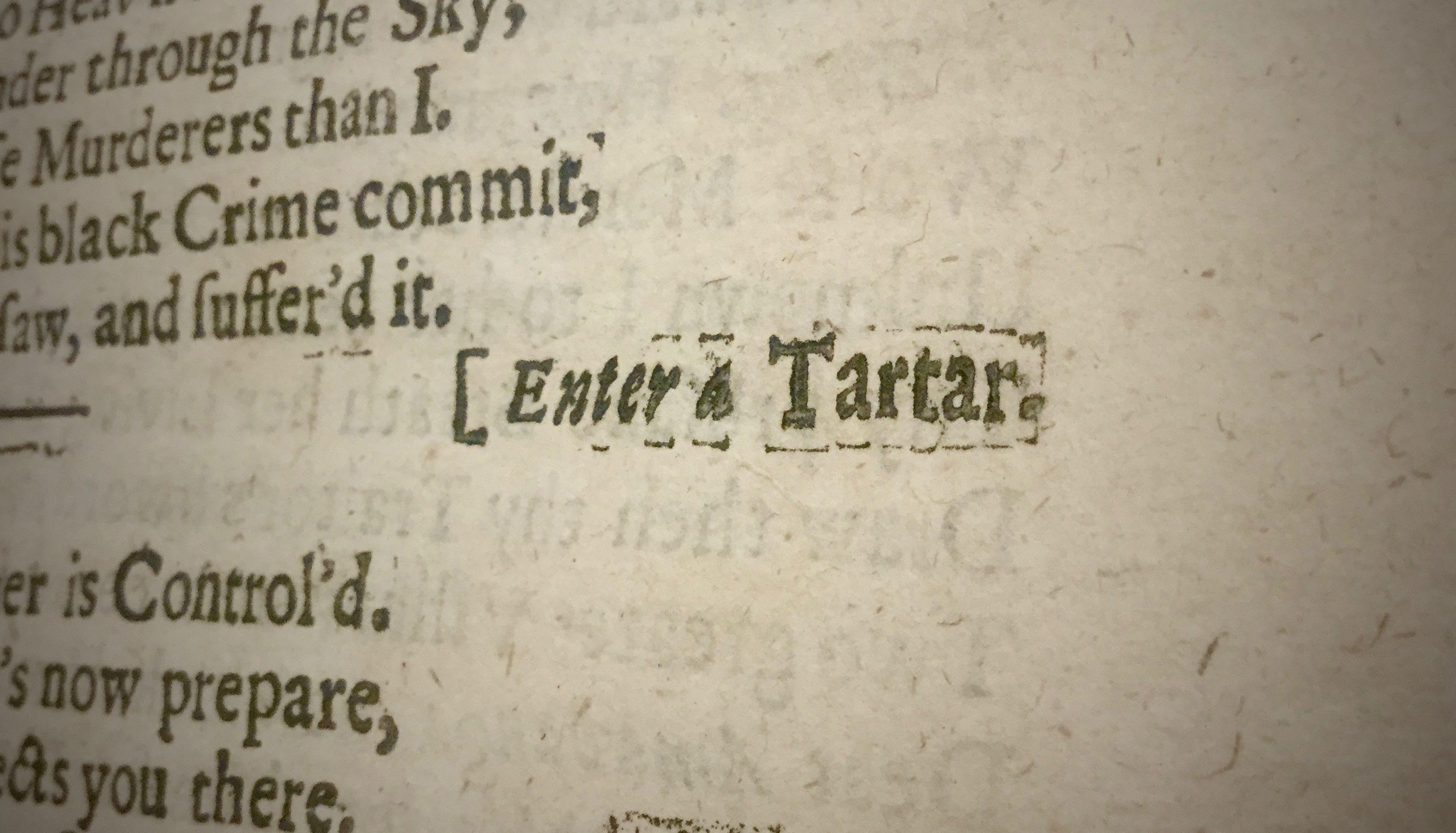

Aside from being one of the eight surviving backstage-plotts of the Elizabethan period in England, the two-part Tamar Cam plays are the only narrative we know to have focused on Mongol-China and Genghis Khan. The extant plott attests to dramaturgical features of Tamar Cam alongside the rich repertory schedule available in Henslowe’s Diary, demonstrating the ways in which the paratexts of “lost plays” reveal the distinctive features of individual company house styles. As part of a larger project delineating industry-wide from company-specific manners of presentation, this past summer of 2018, the Society of Theatre Research sponsored Dr. Elizabeth E. Tavares, assistant professor of English at Pacific University Oregon, to pursue the question to what theatrical allusions of Chinggis Khan and his dynasty refer on Renaissance stages.

There has been no dedicated scholarship on this particular play nor on the staging of Mongols (i.e., “Tartarians”) in English drama. The scholarship surrounding Tamar Cam illustrates the gap in research on how early moderns perceived those peoples living between Russia and China. While work on Elizabethan triumphs by Elizabeth Goldring and Jayne Elisabeth Archer (2016), Bernadette Andrea’s study of Lady Mary Wroth’s engagement with Tartary (2010), and a few notes by Lawrence Manley and Sally-Beth MacLean (2014) mention the play, it is still hotly debated as to whom the titular character refers. Two anthologies of primary documents illuminating sixteenth-century contact with peoples of color are now in print—Daniel Vitkus’s Piracy, Slavery, and Redemption: Barbary Captivity Narratives from early Modern England (2001) and Ania Loomba and Jonathan Burton’s Race in Early Modern England: A Documentary Companion (2007)—they focus almost exclusively on narratives regarding North Africans, Congolese, Egyptians, and those of Jewish descent.

Work undertaken at the Huntington Library unearthed two hitherto unknown sources of the play alongside a wealth of travelogues and ballads engaging with the image of the Tatar. The surviving narrative sources, in the context of allusions current to the Elizabethan repertory, fill in some of the picture of “Tamar Cam” on stage. Of the many possibilities, the play may have included a plot focused on male kinship and succession between Möngke Khan and Temür Khan based on their historical analogues as the Elizabethans would have known them. The narrative of male kinship shared between Möngke and his grandson Temür, perhaps exacerbated with a conflict over succession when Temür was initially sidestepped in order for Kubilai Khan to reign, was a story well in circulation. Second, the play may have focused on female competition. Allusions emphasize the khan’s ability to manage love, and all later plays include competitions between female leads. Incest and polygamy were key features of Tatarian narratives, from Chaucer’s Squire’s Tale and Spenser’s The Faerie Queen to the eighteenth century; as one travel narrative purported, “they Marry their nearest Relations, but not so incestuously as of old they were wont to do” when they “commonly married their own Mothers, Sisters, or Daughters.” The plot makes available the possibility that upon the death of Möngke Khan, part of the conflict might have been Temür being made to wed his aunt in order to secure support for a final military conquest.

If it staged a Mongol-China conflict, it would situate the play within the repertory of global conquerors of the ancient world. The stage business required of Tamar Cam mirror those of several Admiral’s plays, providing an increasingly concrete picture of the house style that distinguished the company from their 1580s competitors. Thus, the performance history of Tamar Cam makes a strong case for starting with theatrical paratexts to map the development of playing companies and, by extension, enliven the industry in which William Shakespeare would come to train. This work is now forthcoming as part of a collection, Reprints and Revivals of Renaissance Drama, edited by Eoin Price and Harry Newman.