News

18 May 2022 / Grants and Awards

The ‘Last Actor-Manager’ – researching Charles Vance

The Stephen Joseph award for 2021 was given to Claire Harding to further her work on Charles Vance, ‘the last actor-manager’. Here she writes about the progress of her ongoing research into his life and work.

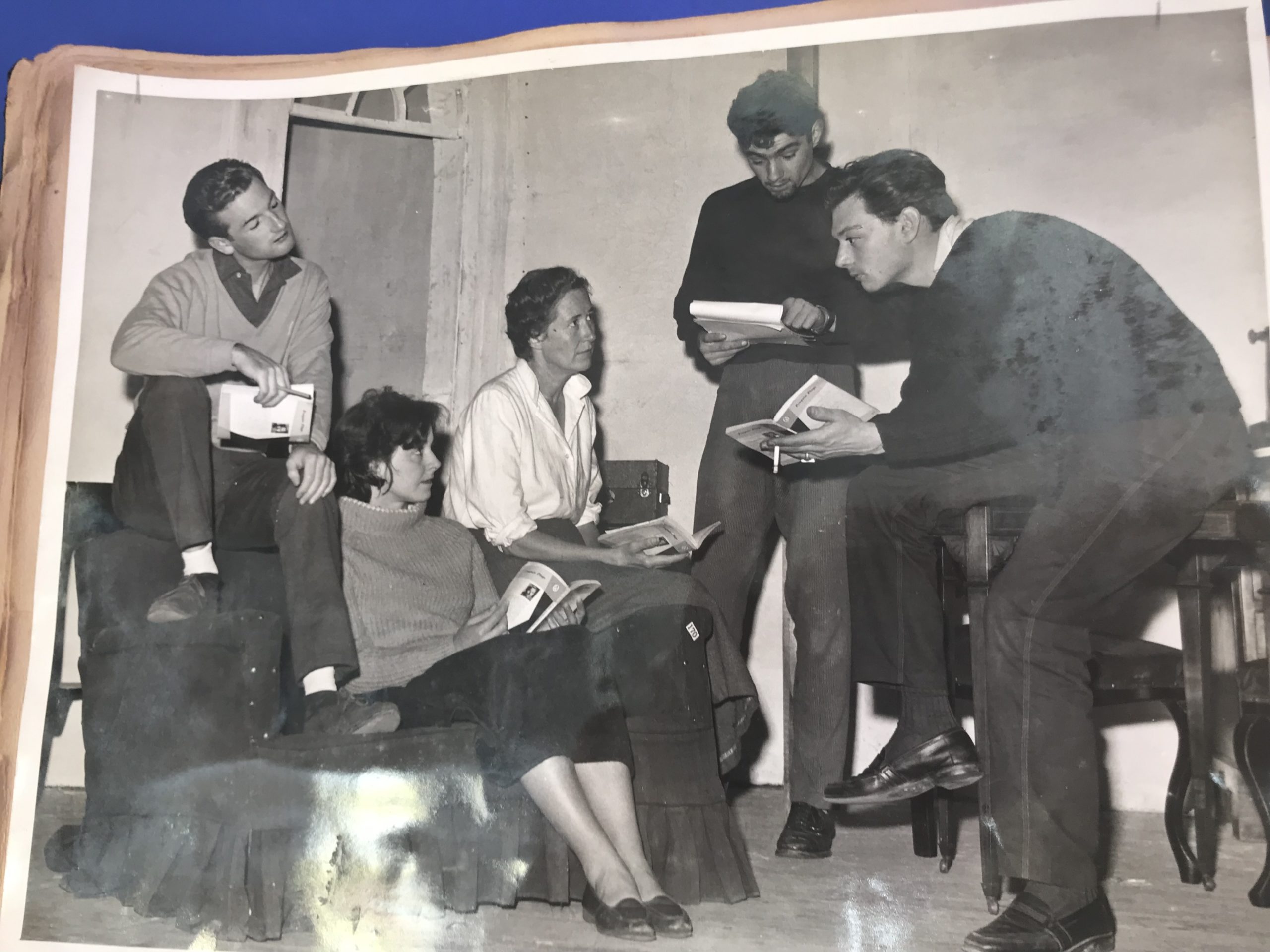

The picture above could have been taken in any rehearsal room, of any group of young actors, in any theatre. But this picture, of a young handsome man perched on the edge of a table, cigarette and script cradled in hand, leaning forward with an intense focus, captures a beginning. A young society girl sits in the middle of the sofa between a sprawling chap and a neat lady. The girl is Imogen Moynihan and the handsome man is Charles Vance. It is the beginning of a theatre company called the ‘group of three’. The start of a journey that in different forms (most notably Charles Vance Productions) lasted for over half a century.

In an article in the Eastern Daily Press, Tuesday October 4th 1960 Charles says, ‘During our tour of this country we are planning to visit schools and play special items like Shakespeare scenes. This is not only to help with their studies, but to develop an interest in the live theatre. School children are then a new generation of theatregoers, and if we can develop their interest in the live theatre now, it will always remain with them.’

Charles was declaring his desire to go into schools and bring Shakespeare to children, some years before the Belgrade Theatre Coventry started their pioneering TIE project. Just one example of how Charles was, in some ways, ahead of his time, an odd idea perhaps for someone who always seemed to have one foot firmly in the 19th century. That flamboyant character, with cloak, hat and Irving’s cane (allegedly), and seemingly every inch the last Actor Manager standing, was engaged in every aspect of theatre and once met, never, ever, forgotten.

Theatre for the community and with the community was a lifelong commitment for Charles which he honoured in a variety of ways: his support for amateur theatre, work in schools, prisons and borstal; and his engagement of rep companies where young actors could start their careers, learn their craft and play weekly rep living and working in the heart of a community. The ‘group of three’ in 1960 had high ideals like a lot of young energetic people, but unlike a lot of young energetic people, Charles Vance seems to have upheld these to the end.

He produced a staggering amount of work. In 1990 Charles declared in his ‘current statistical data’ “As Director: Estimated 1200 productions in repertory, Director of Productions for Buxton, Chelmsford, Torquay, Eastbourne, Wolverhampton, Weston-Super-Mare, Whitby, Folkestone, Arts Theatre Cambridge and Manor Pavilion Theatre Sidmouth. 105 Agatha Christie plays —National and International productions, as well as pantomimes, publications, theatrical magazines and Murder Mysteries.”

I have so far interviewed over 20 people who are all great story tellers. I could, without difficulty, interview another 20, and another 20 more. But I couldn’t interview everyone who knew Charles as at one time, I am told, everyone did.

In an interview Charles once said ‘I considered four professions: the law, Parliament, the Church and acting. They all have one thing in common, they all tell lies in public.’

This was going to be a difficult life to research.

The newspaper archives continue to be an essential tool for the research, and while I don’t subscribe to the ditty ‘it must be true, cos I read it in the paper, didn’t you?’ they at least give us an anchor from which to try to rebuild the ship.

Charles was certainly a bon vivant and teller of tales. He made great claims and not all of them were false. His half-century as a director and producer is very well-documented and relatively easy to follow (in part due to the diligently-kept scrapbooks which were so dear to him); it is his early work in the 1950s which proves an interesting (and ongoing) challenge to trace, in part because understudies and ASMs were not routinely listed in theatre programmes of this period. Charles’s dates and chronologies across the various interviews, pages of the autobiography that he started, and handwritten notes, are inconsistent and occasionally contradictory.

Since Charles sometimes exaggerated his stories, there is a tendency for those who knew him to think all his tales were tall ones, but it is heartening to discover how many of these instances turn out to be at least plausible and, in some cases, provable. To take one year, 1949, there is no reason to doubt Charles worked (as his handwritten notes say) as ‘ASM/understudy’ on the original London production of The Late Edwina Black. Especially since the actor he would have understudied, Stephen Murray, later played Shylock for Charles on tour in 1964. Charles seems to have had a pleasing habit, as producer-director, of employing various names he’d worked with on his way up: Jean Kent, Valentine Dyall, Guy Rolfe, William Lucas, even John Barron who had directed Charles in rep.

Also, in 1949, a piece in the Belfast Telegraph says Charles will appear in a forthcoming film called The Iron Staircase, featuring the great Irish actress Maire O’Neill. Any initial disappointment at there being no film by that name was dispelled with the knowledge that, before release, the film was retitled Stranger At My Door, and Charles does indeed have a small part as Garda Hanlon, his first speaking role on screen. So I continue to try and find something solid behind all the speculation: another unnamed but implausible-sounding film in Hollywood which turns out to be both plausible and nameable; or Charles’s time touring for McMaster and Mac Liammóir, where it’s less a question of if it happened, but when.

The book is becoming one not just of Charles, but of all the characters big and small who have dedicated their lives to the shining stage. Whether that be in the governance of theatre, theatrical administration, the production, back stage, front of house, the theatres themselves which were kept alive, and every contribution that was made from the mighty to the lowly; to the ASM who walked out of a Charles Vance production leaving a direct and angry message painted on a row of bins and positioned outside of the theatre.

He entered the profession of story-telling, and employed hundreds of people to tell stories for him and with him. He might not have thrived in today’s theatre, he was a ‘self-styled anachronism’ but he would have still been fighting for it. In a time of arts cuts in schools and Covid-closed theatres on one hand, and on the other, an emphasis on the healing power of theatre, including the National Theatre’s outreach programmes and a recognition of the need of theatre for all, perhaps his work and beliefs may have been more relevant than ever.

Charles, would have been immensely pleased that an organisation as prestigious and established as the STR should consider him and his work worthy of research. Equally, to have given me an ‘honorarium’ to pursue that course would, I imagine, have swelled his heart. He used to use the word ‘honorarium’ as a label for what he often paid actors; not a wage, not Equity minimum, but an ‘honorarium’. That said, he never missed a payment to an actor, ever. The HMRC may not remember him so kindly, but actors were always paid, even if he had to get into his car and drive the money down to the company manager that night. The Pirate King of the theatre loved the whole business of stage.

Have you got a research project that might be eligible for one of our Research Grants? Applications for this year are now closed, but forms for 2023 will appear on the Research Grants page later this year.