'GATHER ROUND ...' STEPHEN JOSEPH AND THE ART OF CELEBRATION

BARBARA DAY

Barbara Day was among the first students to join the new Manchester University Drama Department in 1962, Stephen Joseph’s first year on the academic staff. She later worked at the Victoria Theatre in-the-Round in Stoke-on-Trent, founded by Stephen Joseph. In between she spent a year studying Czech theatre in Prague, to which she returned to write her PhD in the early 1980s. In 1985 she organised a festival of Czech culture at Bristol University, and became involved in support for Czechoslovak underground and independent culture. After the velvet revolution she settled in Prague as a writer, teacher and translator.

Barbara Day is a member of the Stephen Joseph Committee, which is open to all members of the ABTT, whatever their background, who have an interest in the work and personality of Stephen Joseph. To find out more, see https://www.abtt.org.uk/committees/sjc/ where a wide range of material on Stephen Joseph can be accessed.

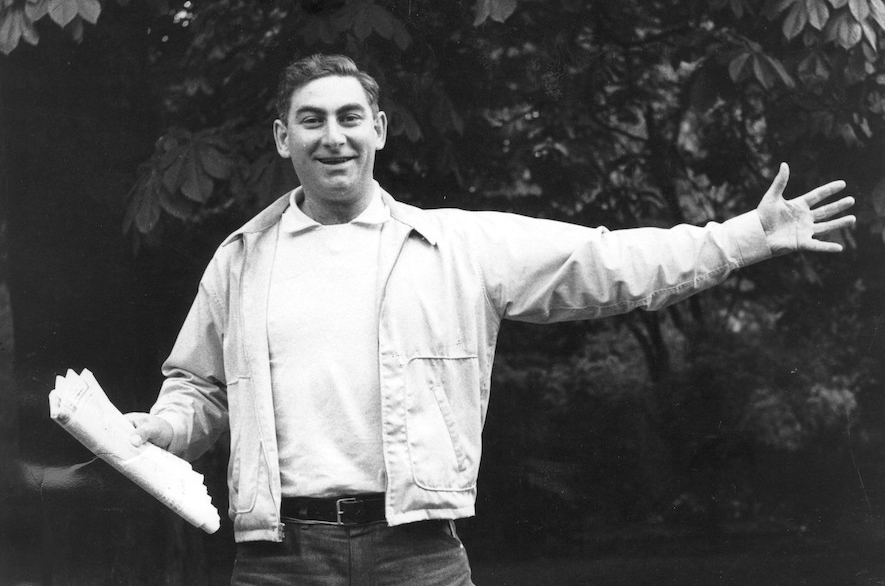

Stephen Joseph, who was born a hundred years ago this year, did not live long enough for his role in contemporary theatre to emerge clearly. He is known above all as the advocate of theatre-in-the-round, but that was one of the outcomes of his thinking, not his primary motivation. Performance in-the-round was for him a reliable way of gathering people together, mentally and physically, in the same space as the action. His aim was a theatre for the people, not in a theoretical or political sense, but as a shared experience. He did not have grandiose theatre visions, but pursued small-scale projects that were intended to demystify the stage. “The phenomenon of the theatre is simply this, that there should be a huge celebration, communally done by audience and actors alike; it says ‘Hurray, we are human beings! We can do things. We have control over our own destiny. Life is exciting! Life is beautiful!” (Joseph, Actor and Architect 115). Scroll to the end of the article for the origin of this and further references.

Stephen Joseph’s life has inspired two biographies: The Full Round (2006) is by a colleague, Terry Lane, who knew him well, and includes some vivid insights. Lane tells an energetic life-story that conveys the charisma of Joseph’s personality. The second biography, Stephen Joseph: Theatre Pioneer and Provocateur (2013) is by Paul Elsam, who exhaustively worked his way through libraries, archives, interviews and correspondence. It is a valuable collection of evidence and witnesses, but it ends on a somewhat inconclusive note. The conviction and drive that made Stephen Joseph the charismatic figure described by Lane remain unexplained. Elsam sees Joseph as a missionary in a society hostile to live theatre, and asks: “How do you popularize theatregoing when it has been unpopular for so long?” (Elsam, Stephen Joseph xiii). Joseph approached the question from a different angle; while he acknowledged a movement away from theatre, his question was: “What is theatre for?” (Joseph, Actor and Architect 114).

Joseph’s early career was interrupted by the war; he spent four years (1941-1945), much of it not directly engaged in hostilities, in the Royal Navy. It was a long interval for a man who had in 1937 been the youngest student to be accepted at the Central School of Speech and Drama. In his final months before demobilisation he wrote to a friend that he had become “less and less certain of anything” (Lane 58); although the description of how he earned the Distinguished Service Cross in 1943 indicates that he could be not only decisive, but downright precipitate (Lane 57).

If we follow Stephen Joseph’s career after the war we may get the impression that he never focused on a single ambition. He entered the theatre by the traditional path of Assistant Stage Manager in a provincial repertory company (1948-49), but a year later started teaching at the Central School of Speech and Drama (1949-55, interrupted by a year in the USA, 1951-52). In 1955, however, he founded Studio Theatre Company Ltd., with a provisional base in Scarborough Library Theatre. It was a project that relied on the one hand on box office takings and on the other on capricious subsidies from trusts, local councils, and the Arts Council. Joseph managed Studio Theatre Company almost to the end of his life, in 1962 moving it to Stoke-on-Trent where a disused cinema was converted into the Victoria Theatre-in-the-Round. In the meantime he became a co-founder of the Association of British Theatre Technicians (1961), the first Fellow of Manchester University Department of Drama (1962), and the author of books on historical and practical aspects of theatre. The University of Iowa in the USA, where he embarked on a post-graduate programme in 1951, complained about “an inability to concentrate his interests” (Lane 84). Did Joseph intend to be a theatre manager or a theatre director, a theatre designer, stage designer or lighting designer? Or – looking at his publications – was he a theatre historian or was he a stage technician? There is evidence that his earliest ambition might have been to become a playwright. Possibly his real vocation was as a teacher. He was involved in all these fields, frequently simultaneously. Did this wide-reaching activity mark Joseph as an indecisive personality, or as one with an unusual goal in mind? And if the latter, what was that goal?

I believe that the concept taking shape in Joseph’s head was a combination of all the elements of theatre, beginning with the space and the audience and including the text and performance, as well as the funding of the operation and its marketing. Further evidence is Joseph’s attention to presentation: when the national anthem should be played, and when not; whether there should be an interval; what refreshments should be served, and when. Every element was thought through and had its own place. To achieve his theatre for the people, Joseph set himself to master the practical skills not only of set building and lighting, but also grant application, fund raising, accounting and financial management. Both biographies, as well as Leslie Powner’s The Origins of the Potteries’ Victoria Theatre, emphasise how this work absorbed Joseph’s time and energy. Joseph could surely have found employment that did not leave him permanently on the edge of existential crisis. Instead, he pursued his aim of bringing theatre to people in the form of Studio Theatre Company. There were times when, to pay the company’s wages, he had to subsidise Studio Theatre from his own bank account, which sometimes necessitated taking on other work himself. Such employment ranged from coal delivery to his appointment in 1961 as the first Fellow of Manchester University Drama Department. Both occupations had an underlying logic: the coal deliveries put him in the physical world of the common man; while the university appointment provided a dramaturgical foundation for the company’s repertoire.

There are indications that Joseph originally aspired to be a dramatist – Lane records that even before he started at the Central School of Speech and Drama, “Stephen had spent much of his teenage years writing juvenile playlets” (Lane 37) – and this becomes quite moving when one realises there must have been a point when he abandoned that ambition and focused instead on encouraging other young writers. According to Alan Ayckbourn, who had originally hoped to become an actor and whose career as a playwright was launched by Joseph’s production of Meet My Father, “Stephen had very strong ideas, although he couldn’t actually put them into practice, about plays” (Watson 34). Ayckbourn refers to “the appalling bits of suggested dialogue he attached to my early plays” (Ayckbourn vi), explaining in a 1981 interview that “suggestions [Joseph] made about the structure were invariably right, about the content or ‘a nice joke to go in here’ invariably wrong” (Watson 34). Joseph directed several of his own plays when a student at the Central School of Speech and Drama and Lane notes that while in the navy, he was hoping the Amersham Repertory Theatre would stage his play Gold and Scarlet (Lane 56). We know that the reason he took a year off from teaching at the Central School was to study playwriting at Iowa University. Lane devotes a chapter of his biography to “The New World”, from which it emerges that as far as writing for the theatre was concerned, the year in America was something of a disappointment. Joseph submitted two plays, What Would Mildred Have Said?, which Lane calls “characterless and bland”, and Murder My Legacy that was “suffering from overtones of melodrama” (Lane 87-88). Soon after that Joseph founded the Studio Theatre Company for which he consistently sought new plays, although he never provided the company with one of his own. Was this because he wanted to avoid charges of megalomania, or had he been convinced that he did not have this gift?

Nevertheless, in his search for plays that would engage a sustainable audience, Stephen Joseph may have enriched the English theatre with more new works than any other theatre practitioner. Maybe it was his conscience that led him to make a last-minute offer to one of his former students from the Central School of Speech and Drama, an aspiring actor called Harold Pinter, whom he had advised “to stick to writing” (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 92). Pinter had come up with The Birthday Party. It was his first play to reach the London stage (1958), and it had a disastrous reception. A few months later, Joseph made a late adjustment to the programme of Studio Theatre Company which enabled him to offer his former pupil an opportunity to direct a revival of The Birthday Party himself. The success of the new production (1959) led to a reassessment of its earlier failure and launched Pinter on his career (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 77-84; Watson 20). However, in recording the role played in Pinter’s rehabilitation by this production, Elsam notes that in spite of Pinter’s “private commitment” to Joseph, he never wrote a play specifically for Studio Theatre Company or directed there again (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 83-84).

In the Studio Theatre production of The Birthday Party, Pinter had the interesting experience of directing two fellow playwrights whose prospects at that time were just as promising (or as uncertain) as his own: David Campton in the role of Petey and Alan Ayckbourn as Stanley.[1] They were also protégées of Stephen Joseph, who had included Campton’s play Dragons are Dangerous in the company’s first season in 1955. David Campton was already in his thirties when in 1957 he abandoned a secure career with the East Midlands Gas Board to join Studio Theatre Company as actor, director and playwright; Elsam notes that he brought stability to the company (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 105-106). Thereafter Campton wrote original plays as well as making adaptations for the company, all of them directed by Stephen Joseph. Ayckbourn remembered that Joseph “encouraged and channelled [Campton’s] writing towards what was then the comedy of menace school, and threw in his thoughts on nuclear disasters. […] I’m never quite sure how David’s talent would have developed, had he been allowed not to be so strongly dominated by Stephen […]” (Watson 33).

Terry Lane notes in his biography that Joseph was also the first to stage the work of playwrights Robert Bolt, Richard Gill, Joan Macalpine and James Saunders. He opened the Studio Company stage to a playwright he found among his Manchester students, Mike Stott, staging The Play of Mata Hari (1965). Stott moved on to work on Peter Brook’s US and Shakespeare’s Tempest, before writing the north-country farce Funny Peculiar. Trevor Griffiths, who first met Joseph in 1963 and who, like Campton, had left a secure job to become a full-time playwright, acknowledged in an interview that it was Joseph’s concept of the open stage that helped him to realise the possibilities of writing for theatre (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 120-122).

The playwright most closely associated with Joseph is Alan Ayckbourn, who remained loyal to him up to and beyond his death, although not to the extent of supplanting Peter Cheeseman as director at the Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent, in spite of being ordered to do so by Joseph in 1966. Ayckbourn was engaged by Joseph as stage manager and actor in 1957. When he complained about his roles, he was told to go and write himself a better one (Walker 103). This turned out to be The Square Cat (1959), and Ayckbourn went on writing for Studio Theatre Company, first in Scarborough and then in Stoke-on-Trent, where in 1962 he was a founder member of the Victoria Theatre-in-the-Round. Soon afterwards came the local success of Mr Whatnot (1963), a play written to be performed without scenery that includes several journeys “across acres of garden, down dark passages and even in speedy vehicles along the highway” (Joseph, Theatre in the Round 57). Ayckbourn directed it himself, but when a London management reconceived the production and sacked Ayckbourn, its transfer was a disaster (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 23). In defiance of the critics, Joseph encouraged Ayckbourn to write another play, which Joseph directed at Scarborough in the summer of 1965 as Meet My Father (Lane 224). This time Joseph advised Ayckbourn to avoid the innovation of Mr Whatnot and demonstrate to critics and audiences that he could write a well-made play. Two years later, and six months before Stephen Joseph’s death, the play became a West End hit under the title Relatively Speaking (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 58). Ayckbourn eventually, in 1996, succeeded in converting the former Odeon cinema into a purpose-built theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, named after Stephen Joseph (Lane 121, Elsam, Stephen Joseph 8).

Stephen Joseph’s holistic approach to theatre could be characterised as dramaturgical. Dramaturgy was an unfamiliar concept in the British theatre of the 1960s, where the function of the dramaturg was still understood as relating specifically to the text and history of written works. In reality, it concerns the construction and connectivity not only of pièces de théâtre but of the theatre company itself, the reason for the theatre’s existence – what it is doing in this place at this time. It is a question of philosophy, ideally planned in advance by the director and dramaturg together. Every theatre has a dramaturgy of some kind, and when this is not meaningfully planned the theatre is all too likely to let the marketing department lead it by the nose. Dramaturgy is an essential element in creating the profile of the theatre and binding it to its audience. This was the direction in which Stephen Joseph’s instinct was leading him.

When Stephen Joseph was asked to lead the diploma course for the Drama Department of Manchester University, dramaturgy was on the syllabus. It is interesting that this post-graduate programme should have been launched in the autumn of 1963, the same year that Kenneth Tynan became the first official British dramaturg, albeit termed Literary Manager, of the National Theatre. According to George Taylor (among the first students and later a lecturer In Manchester’s drama department), Joseph’s course would have been best described as “Dramatic Theory”, although he writes that: “I remember [Joseph] did explain how the term and function of a dramaturg was used in the German theatre” (Taylor, email). Joseph launched the dramaturgy course with the statement: “There’s Aristotle, there’s Brunetière – and I have a few ideas of my own.” (Millington, Jackson and Fielding 1). According to Terry Lane, Stephen Joseph had encountered the French scholar Ferdinand Brunetière (1849-1906) and his essay La loi du theatre (translated as The Law of the Drama) in America (Lane 188), probably during his year as a student of play-writing at Iowa University. Brunetière’s dismissal of the neoclassical rules as merely “devices which may at any time give way to others” (Brunetière 71) was reflected in Joseph’s oft-repeated statement that “Theatres should self-destruct after seven years” (Millington 1). Joseph was inspired by, and possibly identified with, Brunetière’s concept of the heroes of dramatic works as “architects of their [own] destiny” (Brunetière 76) – we may note his exclamation “We have control over our own destiny” in the opening paragraph of this article. Drama occurs when the central character demonstrates “a will … to set up a goal and to direct everything toward it, to strive to bring everything into line with it” (Brunetière 75). The stronger the central character and the more insurmountable the obstacles, the more profound and satisfying the drama. Brunetière used Racine’s Phèdre as an example, and in 1957 Joseph chose this play, with Margaret Rawlings in the title role, for Studio Theatre Company’s farewell production in London.

Joseph’s year in the USA not only introduced him to Brunetière but also confirmed the practicality of staging in-the-round. “There was drama long before anyone wrote a play”, he writes in the Prologue to The Story of the Playhouse in England. “When, ages ago, men danced and used their dance to tell a story, that was the beginning of drama. They used disguise, such as costumes and masks, to help them play characters other than themselves; they told a story; and people watched” (Joseph, Story of the Playhouse 2). He illustrates this with a photograph from Portugal of a spontaneous contemporary performance of a traditional dance, the audience encircling the dancers. This natural law of the crescent/circle has been rediscovered in different ages and different circumstances, often as an instinctive solution at a time of need – artistic, legal, economic or political. By the time Joseph reached America it had been revived there when Margo Jones created Theatre ’47 in Dallas.[2] The publication of her book Theatre-in-the-Round (1951) coincided with Joseph’s visit, and Joseph refers to it in his own book of (almost) the same title, published in 1967. The Dallas experiment had been followed by the realisation that in-the-round staging was the practical solution to providing every town in America with its own economically viable professional theatre. Joseph visited seven of these, and studied the plans of more, noting the variety in their capacity (from 100 to 2,000), origin (purpose-built or reconstructions), shape (square, circular, rectangular, oval) and style (Joseph, Theatre in the Round 29-32).

One of Stephen Joseph’s contemporaries who similarly looked beyond the boundaries of the conventional was Peter Brook. According to Lane, Brook and Joseph had known each other since the late 1940s (Lane, 72). However, Brook, four years younger, and excused active military service because of a childhood illness, made his name first in the traditional surroundings of the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon and Covent Garden Opera in London. Nevertheless, on a visit to the Victoria Theatre-in-the-Round in Stoke-on-Trent, Brook was generous towards what was probably a fairly standard production of George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, writing: “…it is unlikely that anywhere in London that evening the theatrical temperature was nearly as high as in Stoke” (Brook 144).

That visit probably took place during Brook’s tour of northern universities to deliver a series of four lectures, sponsored by Sidney Bernstein and Granada Television. The first lecture was given in Manchester early in 1966[3] and hosted by the university (Brook’s tour continued to Keele – in the locality of Stoke-on-Trent – Hull and Sheffield). The text, under the title “The Deadly Theatre”, was to become the opening chapter of Brook’s book The Empty Space (supplemented by the chapters called “Holy Theatre”, “Rough Theatre” and “Immediate Theatre”). Although controversial at the time, The Empty Space is now established as a key text of late twentieth century theatre. It opens with the words: “I can take any empty space and call it a stage. A man walks across this empty space while someone else is watching him and this is all that is needed for an act of theatre to be engaged” (Brook 11). Peter Thomson, then a junior lecturer in Manchester University Drama Department, remembers the lecture partly because of “Brook’s implicit endorsement (whether conscious or coincidental) of the dramaturgy of Stephen’s well-loved Brunetière”, but “mostly because Brook spoke in such a priestly (sacerdotal) voice. It was the kind of voice in which some of the Methodist preachers of my boyhood used to improvise prayers. There was a spiritual force that made his words hover” (Thomson).

According to Lane, Stephen Joseph sought to puncture the solemnity of the occasion by encouraging two students to ask Brook questions about the purgative effect of Greek tragedy; the joke derived from the fact that Brook’s father, a Russian Jewish immigrant, had developed a successful pharmaceutical business out of an effective laxative (Lane 181). Lane’s story, whose source was Mike Stott, could have been a later elaboration, but it exemplifies Brook’s tendency to mystify theatre, and Joseph’s tendency to demystify it. Brook and Joseph took a similarly analytical approach to theatre, but whereas Brook worked backwards from the temples of “the deadly theatre” (Brook 11-46), Joseph passed them by and chose from the start to work on small stages with inexperienced performers. They both viewed theatre as a story acted out for a gathering of people, but whereas in Brook’s case an international audience watched stories from Persian poetry or from Ugandan mountain people, in Joseph’s case a local community focused on tales told over the breakfast-table or on the top deck of a bus stuck in traffic. Both Brook and Joseph were responsive to the challenge of foreign audiences. In 1953 Stephen Joseph and a group from the Central School performed at the Fourth World Festival of Youth and Students in Bucharest, returning via Warsaw at the request of Polish colleagues. The double bill of a medieval mystery play and Joseph’s avant-garde work, The Key, engaged audiences from an environment of ideologically based Socialist Realism (Lane 95-99; Elsam, Stephen Joseph 124-125). Brook, in “The Deadly Theatre”, describes how, while touring Shakespeare’s King Lear in 1964, “the best performances lay between Budapest and Moscow. […] These audiences brought with them […] an experience of life in Europe in the last years that enabled them to come directly to the play’s painful themes.” (Brook 25).

In an assessment of Joseph’s legacy, Elsam muses on why the credit and fame for visionary ideas devolved on Brook rather than on Joseph (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 41). Elsam puts Joseph’s low profile down to his naturally subversive nature, and believes that he “resolved early on to be something of an intellectual and stylistic moving target” (Elsam, Stephen Joseph 41). The word “resolved” however attributes a calculating streak to Joseph that was alien to his personality. He was simply in pursuit of Brunetière’s “essential characteristic” (Brunetière 68) shared through performances that capture the moment which for each audience is a unique here and now and yet is repeated at every performance. As a theatre director, Joseph’s method was to bring together the constituents of drama, as he had determined them: a play centred on a strong-willed hero prepared to struggle against redoubtable odds; a performance space shared by actors and audience where the public feels involved in the action; and performers who can move instinctively in such a space. Years later, Peter Cheeseman was fascinated by Joseph’s “vision of the spatial relationship between the actor and the audience and his way of radically appraising the importance of its components […] I had never met anybody who had such a clear, radical vision of the essential importance of the physical structure of theatre” (Giannachi and Luckhurst 14). Ayckbourn quotes Joseph as saying: “Directing is very, very simple, all you need to do is to create an atmosphere in which other people feel confident to create” (Elsam, “Remembering Stephen Joseph”).

Joseph’s experience as a director was with his own team, Studio Theatre Company, on tour and in Scarborough Library Theatre and Stoke Victoria Theatre (1955-1965), bookended by his early experiences with students at the Central School of Speech and Drama (1949-1955), and his final four productions with the Manchester students (1962-1965 – however, only the first of these, The Bacchae, was staged in the round). He did not distinguish between the students and professional actors. It was the young people’s inexperience that he valued, and the absence of acting conventions. He was trying to encourage his actors to inhabit the stage as though it were the real world, in the course of which they would find ways to relate to each other naturally. Cheeseman quoted Joseph as saying that “theatre in the round is structured like life, and that consequently movement organises itself like it does in real life. … In the circle everybody is equal and everybody has equal access to each other.” (Giannachi 14). It was not unusual for him to ostentatiously ignore the actors in the course of the rehearsal, choosing to read a newspaper or undertake some practical task. For this, Joseph was condemned by some actors as a poor director.

The results do not bear this out. In his dissertation on Joseph’s work, Rodney Wood writes about his productions at the Central School of Speech and Drama and with Studio Theatre Company that:

[h]owever idiosyncratic his methods and however slight his apparent direction, his productions were never dull, and, at a time when students were often drilled in their parts like puppets, his actors always looked relaxed and convincing in their roles. (Wood 73)

In 1963 Joseph’s production of John Whiting’s The Devils[4] with Manchester undergraduates was performed in Parma’s Teatro Reggio – a traditional Italian opera house with a large and elaborate picture frame stage – at the Eleventh Festival of University Theatre. The critic of a local paper, Il Resto del Cortino, wrote (6 April 1963): “La regia di Stephen Joseph ha conferito al lavoro un ‘intensa drammaticità” (The direction by Stephen Joseph gave the work an intense dramatic feel). The following year, David Robertson (later to play the leading role in Dion Boucicault’s The Shaughraun) compared the effect of Joseph’s third production at Manchester, Christopher Marlowe’s Edward II, to “an express hurtling through a tunnel, thrilling but clear” (Millington 26).

Joseph rehearsed this production of Edward II from October 1963 through to its performance in May 1964 as part of Manchester University’s Age of Shakespeare Festival. A collection of oral testimonies, Remembering Stephen Joseph, the outcome of a gathering in 2017 of his Manchester students, contains some spontaneous insights into his method. Michael Bath (who played Leicester), recalled that:

Once, while actors were onstage working away, he went over to the ones waiting to enter from stage left, as rehearsed. Talking to them conspiratorially, he’d get them to come on from stage right – just to see how people onstage would handle it. (Millington 19)

Christopher Baugh, when he asked where he should come on (in the role of Arundel), was told that he had to “find out” (Millington 6). Mike Casey, playing Young Spencer, remembered how Joseph boosted his confidence by praising his decision to make an impromptu move at a key moment (Millington 23-24). Tony Jackson, on the other hand, recalled that, when he was struggling in the role of the king, “Stephen sprang into life, jumping onto the stage to work with us and among us…That was, for me exhilarating” (Millington 25). Jackson was, however, stunned to discover later that Joseph had been genuinely distressed at having relapsed into being “an old-fashioned director”, and reflected that: “[I]t also made me begin to realise just how different Stephen’s view of theatre practice was from ‘the norm’. He had not just been a ‘lazy’ director (as I’d suspected) but was struggling to put into practice a passionately held philosophy of theatre that I needed to wake up to” (Millington 25).

Joseph’s subsequent and final production was Dion Boucicault’s The Shaughraun (1965). Both Elsam and Lane quote the notes that (according to Lane) Joseph gave to his proxy for the rehearsals: “Don’t read the play. Listen to and watch the actors,” an order that is immediately followed by: “Never tell the actor how to say a line, where or how to move. Advise when asked, enlarge don’t limit, say it five different ways.” (Lane, 187).The outcome of this method of work was productions that stimulated their audiences by their speed and energy and by the confident and dynamic performances Joseph summoned from his players, who were expected to be responsible for their own moves.

However, a feature of Joseph’s career from the beginning had been his long absences from one part or another of his simultaneous activities. Ayckbourn remembers that it was several weeks after he started working for Joseph that he actually met him (Watson 16). By the early 1960s, Joseph’s commitment to his Manchester students involved an almost permanent absence from Studio Theatre Company, which, at a critical moment, he had put into the hands of his company manager, Peter Cheeseman. It was Cheeseman who found and negotiated the premises in Stoke-on-Trent as a permanent home for Studio Theatre Company. Joseph retained the title of Managing Director of Studio Theatre Limited, while appointing Cheeseman director of the Victoria Theatre-in-the-Round (Powner 124). Cheeseman, who followed Joseph’s practice of fostering new playwrights, also developed the locally sourced documentary – a genre for which Stoke became renowned. Although inspired by Joan Littlewood’s Oh What a Lovely War!, the Stoke documentaries surpassed Littlewood’s manifestos in their rigour and objectivity. In the first documentary (The Jolly Potters, 1964), Cheeseman experimented with improvisation, one of the strategies Joseph had introduced in Manchester two years earlier. But whereas Joseph had used improvisation as an exercise to release the actors’ minds and bodies, for Cheeseman initially improvisation formed the basis of the dialogue; this process however he abandoned, adopting the technique of what is now called “verbatim theatre”, where every word has to be authentic, taken either from historical texts or recorded interviews. The drama comes into existence without the use of original or creative writing; the playwright does not write a play, but works the material for it to be wrought into existence. Whether, had it not been for his illness, Joseph would have been a part of this, one cannot tell. By this time, however, Joseph was fighting the disease that killed him and also, tragically, fighting Cheeseman for control of the theatre – primarily administrative and financial control, as he spent too little time there to be involved in the creative process.

But what is certain is that the New Victoria Theatre-in-the-Round (now in neighbouring Newcastle-under-Lyme) would have not existed without him. Nor would the theatre that bears his name in Scarborough, nor the Stephen Joseph Studio in the German church on the campus of Manchester University. He also indirectly influenced the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh, whose founder in 1962 was his former company manager and biographer Terry Lane, and the Bolton Octagon, founded in 1967 by Robin Pemberton Billing, son of Joseph’s legendary housekeeper Elsie Veronica Pemberton Billing, known invariably as P-B. Stephen Joseph provided the conditions and mentoring not only for playwrights but for other theatre workers (actors, directors, designers, technicians), including Roland Joffé, Ben Kingsley, Mike Leigh, Alan Plater, Clare Venables, Clifford Williams and Faynia Williams. He was a theatre visionary of the generation and stature of Peter Brook and Jerzy Grotowski, but inclined away from self-aggrandisement and towards simplicity. His knowledge of and instinct for the origin of theatre, his fascination with the structure and content of the play as text, his mastery of practical skills and his belief that actor and audience must share the theatre space physically and metaphorically, came together in his best work. Stephen Joseph could be compared to Brunetière’s heroes of the drama, as one who did not “drift with the current” but had a will “to set up a goal and to direct everything toward it, to strive to bring everything into line with it.” (Brunetière 75) His life, at one level spontaneous, improvisatory and seemingly iconoclastic, was in fact extremely disciplined. It was devoted to overcoming obstacles methodically and providing conditions for creation in which all could share, resulting in a communal theatrical experience – one which he knew existed naturally, for that was the Law of the Drama.

Works cited

Ayckbourn, Alan. Foreword to Stephen Joseph: Theatre Pioneer and Provocateur. London: Bloomsbury 2014.

Brook, Peter. The Empty Space. London: McGibbon & Kee 1968. Cited from Penguin Modern Classic 2006.

Brunetière, Ferdinand (tr. Philip M. Hayden). The Law of the Drama. New York: Dramatic

Museum of Columbia University 1914.

Císař, Jan (tr. Andrew Philip Fisher and Julius Neumann). The History of Czech Theatre: a survey. Prague: AMU Press 2010.

Elsam, Paul. Stephen Joseph: Theatre Pioneer and Provocateur. London: Bloomsbury 2013.

– – – “Remembering Stephen Joseph: Alan Ayckbourn’s Memories of Stephen Joseph” (interview). Alan Ayckbourn’s Official Website. http://biography.alanayckbourn.net/styled-37/page-11/page-7/

Giannachi, Gabriella and Luckhurst, Mary. On Directing. London: Palgrave Macmillan 1999.

Joseph, Stephen. The Story of the Playhouse in England. London: Barrie and Rockliff 1963.

– – – Theatre in the Round. London: Barrie and Rockliff 1967.

– – – Appendix 2 “A Brains Trust” in Actor and Architect ed. by Stephen Joseph. Manchester: Manchester UP 1964, 91-115.

Gussow, Mel. Conversations with Pinter. London: Nick Hern Books 1994

Lane, Terry. The Full Round: The Several Lives and Theatrical Legacy of Stephen Joseph. Castiglione del Lago: Duca della Corgna 2006.

Millington, Bob, Tony Jackson and Athene Fielding (eds.). Remembering Stephen Joseph: Theatre Visionary and Pioneer. Leeds: Book Empire 2019.

Powner, Leslie. The Origins of the Potteries’ Victoria Theatre. Place of publication not given: The Arnold Bennett Society 2017.

Taylor, George. Email to Barbara Day, located in Day archive. 25 March 2021.

Thomson, Peter. Email to Barbara Day, located in Day archive. 18 November 2020.

Walker, Rachel. “‘One of the few theatres in England who really cares about dramatists’: New writing at the Victoria Theatre, Stoke-on-Trent in the 1960s”. Theatre Notebook Vol 73, no. 2, 102-120.

Watson, Ian. Conversations with Ayckbourn. 2nd edition. London: Faber and Faber 1988.

Wilmeth, Don B., Christopher Bigsby (eds.), Cambridge History of American Theatre, The. Vol III: Cambridge: CUP 2000. 229-231.

Wood, Rodney Davies. Stephen Joseph: his work and ideas. Thesis (M.A.) Cardiff: University College 1980.

[1] Ayckbourn much later told the story, subsequently repeated by Pinter, of how, during rehearsals of The Birthday Party, Ayckbourn asked the author/director for help in interpreting his role, and “this fellow, Harold Pinter, put his glasses up on his nose and said ‘Mind your own business!’” (Gussow 111-112).

[2] Jones named her theatre after E. F. Burian’s D34 in Prague, with the difference that whereas Jones changed the number every year on New Year’s Eve “to remain contemporary at all times” (Wilmeth 229), Burian even more progressively changed the number at the start of the preceding autumn season (Císař 306).

[3] Michael Kustow gives the date as 1 February 1965 in Peter Brook: A Biography (Bloomsbury 2005); but most people I have consulted think that early 1966 is a more likely date for the Manchester lecture. I was in my final year in the Drama Department of Manchester University in 1964/65 and there is no mention in my diary of any such lecture on 1 February 1965.

[4] John Whiting, who died aged 45 in June that year (1963), was greatly admired by Joseph as being more original and typical of the new style than John Osborne (Joseph, Story of the Playhouse ). The Devils, based on Aldous Huxley’s novel The Devils of Loudon, had been premièred by the Royal Shakespeare Company the previous year.