Vol. 72, No. 1

pp. 1-64, 2018

Articles

-

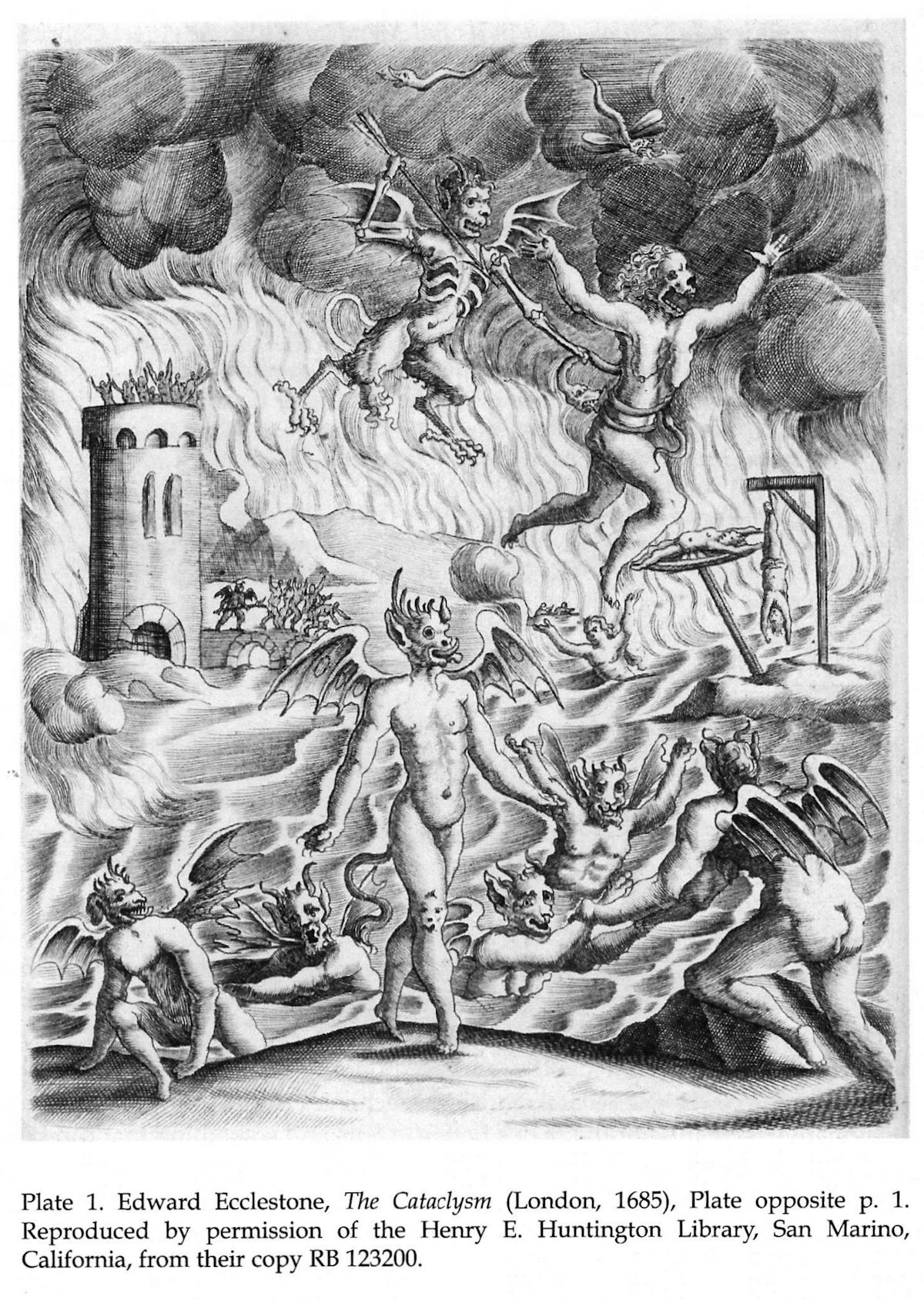

Edward Ecclestone's 'The Cataclysm: New Engravings of Restoration Stage Scenery?

Peter Holland

Peter Holland discusses the possible relationship of a series of sensational scene pictures published in 1685 to actual contemporary staging practices. The engravings are reproduced here by permission of the Henry E. Huntington Library for readers to examine for themselves.

We are not so well supplied with images of Restoration stage scenery that we can afford to ignore any images with possible connections to Restoration theatre practice. Tim Keenan’s careful and thorough survey, in his excellent study of Restoration Staging, 1660-74, covers the familiar printed images, from William Dolle’s five engravings in Elkanah Settle’s The Empress of Morocco (1673) and the frontispiece to Louis Grabu’s Ariadne (1674) to Joe Haines’s Prologue riding an ass (A Fatal Mistake (1692)) and the frontispiece to John Eccles’s Theatre Musick (1698), before turning to John Webb’s drawings for Sir William Davenant’s The Siege of Rhodes and for Roger Boyle’s Mustapha (Keenan 11-33). Keenan offers a single European example as a parallel, from the Schouwburg Theatre in Amsterdam (18), just as Cary DiPietro turns to an engraving by Charles-Nicolas Cochin the Younger after Giacomo Torelli’s design for Francesco Sacrati’s La Finta Pazza (Petit Bourbon, 1645), when he wants to find an image that might suggest what a set description in the 1674 version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest looked like for a design “compos’d of three Walks of Cypress-trees, each Side-walk leads to a Cave… The Middle-Walk is of a great depth, and leads to an open part of the Island” (DiPietro 179, quoting Shadwell 5).

-

Rich's Register: The Chatsworth Volume

Terry Jenkins

Research into eighteenth-century theatre has been considerably aided by two handwritten volumes now given the generic title “Rich’s Register”. They contain a day-by-day record of performances at the two main London theatres. The first volume is now in the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington D.C. and covers the years 1714 to 1723. It shows the performances and nightly takings at Lincoln’s Inn Fields theatre, and the play performed at Drury Lane the same night. The second volume, 1723-1740, is in the library of the Garrick Club in London, and encompasses the move of the company from Lincoln’s Inn Fields to the new Covent Garden theatre in 1732. Both volumes are written in the same hand throughout, and one can see from a couple of comments in the text of the second volume that the writer was supposedly Christopher Mosyer Rich.

-

From Vocalist to "Inventor of the Dresses": Vincenzo Sestini's career at the King's Theatre in the Haymarket

Audrey T. Carpenter

The King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, or the Opera House, was for many years licensed to perform Italian opera only on two days in the week and proprietors had to ensure the ongoing appeal of its performances to a fairly limited and critical clientele. When the 177475 season opened the new management1 decided to promote more light-hearted opera buffa in addition to opera seria. Advertisements offering subscriptions for the coming season reflected this (Public Advertiser, 22 Sep. 1774): the popular tenor, Signor Lovattini was to return as first buffo, and Signora Sestini would be first buffa. The Italian soprano, Giovanna Sestini, had been performing to acclaim in Lisbon and she had travelled to London to take leading roles opposite Giovanni Lovattini in the comic operas (Carpenter, Giovanna Sestini 1530). Also listed in the advertisements was Signor Sestini who was to be “last man” in the serious opera and third buffo in the comic opera.

-

Darkening the Auditorium in the Nineteenth Century British Theatre

Russell Burdekin

Today when we go to the theatre we expect the house lights to go down, heralding the start of the stage action. Any exception to this would be seen as seeking to impart some particular angle or significance to the stage action. However, prior to the late nineteenth century, a fully lit auditorium1 was the norm. This change in theatrical practice has received little attention. Wolfgang Schivelbusch (207) wrote that the move to a darkened auditorium was not simple and straightforward and had proceeded in “fits and starts” while Michael Booth concluded that it “did not become general in the West End until after First World War” (Theatre 62). Neither provided much detail on nineteenth-century practice, on which Terence Rees (219-221) and Gösta Bergman (298-300) are the fullest, although even here the discussion is limited. The aim of this paper is to give a better idea of its erratic history.

BOOK REVIEWS

Beckett's Creatures: Art of Failure after the Holocaust

Joseph Anderton

Staging Beckett in Great Britain

David Tucker and Trish McTighe (eds)

Eighteenth-Century Brechtians: Theatrical Satire in the Age of Walpole

Joel Schechter

Renée Houston: Spirit of the Irresistibles

Miranda Brooke

Staging the Peninsular War: English Theatres 1807-1815

Susan Valladares

The Cambridge Introduction to Performance Theory

Simon Shepherd

Edward Ecclestone’s ‘The Cataclysm: New Engravings of Restoration Stage Scenery? *** Rich’s Register: The Chatsworth Volume *** From Vocalist to “Inventor of the Dresses”: Vincenzo Sestini’s career at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket’ *** Darkening the auditorium in the Nineteenth Century British Theatre.