News

10 June 2016 / Blogs

NRN Blog: Innovation in Research, Innovation in the STR

We asked our previous Chair, David Coates, to write about innovation in his research and in the STR at large — and we’re glad he did! David is a part-time doctoral candidate at the University of Warwick writing a thesis on Private and Amateur Theatricals in Britain, 1830-1914. He completed his MA by Research in 2010 with a thesis that interrogated the social, cultural, political and theatrical significance of the Chatsworth House Theatre and the Duchess of Devonshire’s Private Theatricals, 1880-1914.

David has been a member of STR since 2011 and sat on the Executive Committee after founding the NRN, from February 2012 until September 2015. He’s also a member of TaPRA, and was fortunate enough to sit on the Executive Committee as a Postgraduate Representative until Summer 2015. He continues to attend the Historiography working group at both TaPRA and at IFTR, and for the latter organisation acted as Administrator for the Warwick World Congress in 2014.

Innovation In My Research

The Call for Papers for the NRN’s annual symposium draws attention to the importance of innovation in academia and states that innovation is ‘at the core of our development as scholars’. Though undoubtedly true, our determination to find innovation in our work has occasioned a proliferation of micro histories that – as fascinating as they may be – ultimately fail to acknowledge the bigger picture. Equally, it has resulted in skewed theatre histories and has left some areas of our discipline heavily under-researched and underappreciated. Amateur theatre pre-1914 is but one of these areas.

Amateur theatricals in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have been investigated by a handful of scholars, including Sybil Rosenfeld, Gillian Russell, Kate Newey and Mary Isbell. More often than not, these histories have categorised and compartmentalised amateur performance into distinct types, such as Private Theatricals, Shipboard Theatricals, Garrison Theatricals and University Theatricals. These microhistories have their place – they’ve been enlightening and have contributed hugely to my research – but I think they’ve missed something crucial. They’ve lacked the scope to allow for understanding the relation these forms have to one another.

Way back in 2010 I started my PhD with an emphasis on Private Theatricals in country houses, but that focus very quickly expanded. You could say that I got distracted. I was convinced that so little had survived to tell the story of amateur theatre in the period, that any material to have made it through the last two centuries relating to amateurs in any form would help to contextualise my rather niche field. The truth was that there was more evidence surviving than I could have imagined and seeing as much of it as possible hasn’t been light on my pockets or my time. I’ve taken over 24,000 images of materials relating to nineteenth century amateur theatricals in Britain, and have created a database of the thousands of performances that I now know to have taken place. This database continues to grow!

It’s safe to say that some colleagues were concerned by the increasing scope of my project and I was encouraged to narrow my focus. Others thought I was mad to have gathered so much material and yet not put pen to paper to start writing my thesis. I too was beginning to question it! But, luckily I knew that there was method to my madness. In doing all of this research, the innovation came from the good fortune of being able to take a holistic approach. By looking very broadly at the field, at the various forms of amateur theatre previously studied, and at many lesser know examples of amateur performance, I was able to fully explore their interconnections for the first time.

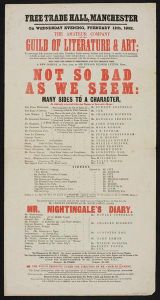

The research has revealed a group of what I term ‘professional amateurs’, who were invited to country house parties, were performing in charity theatricals in the West End, and were connected to the Canterbury Old Stagers and Windsor Strollers – two of the country’s most elite amateur societies.[Figure 1] Many of the male ‘professional amateurs’ had performed at Eton, Harrow, Cambridge or Oxford together, had mingled together at the Garrick Club, and had been involved in theatricals onboard ships and at garrisons. The well-documented literary theatricals of Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, which otherwise had been assigned to a literary culture, could very firmly be connected to this world of ‘professional amateurs’.[Figure 2] Thus, my research reveals a network of aristocratic and middle class men and women who formed what could be perceived as a national amateur theatre network, well before any formal organisations, such as the National Operatic and Dramatic Association (1899), had been founded in Britain.

This holistic view has done much more than revealing the interconnections between amateur theatrical forms in the period. It’s also exposed interconnections with amateur sports and amateur music making, consequently documenting the changing attitudes to labour and leisure time through the century. I’ve uncovered the macro – at least in Britain! – but this work could undoubtedly be extended to look at the profusion of materials across Europe, North America and the Empire.

Finally, by taking a step back I’ve also uncovered a distinct repertoire for amateur theatre in the period. This repertoire may be used to challenge our current understanding of the nineteenth century theatrical canon – a canon which presently upholds the notion that only professional theatre is worthy of study. Expelling the hierarches and binaries associated with ‘amateur’ and ‘professional’ theatre when looking at the canon, and beyond, could provide fresh perspectives.

Through this research I’ve become acutely aware that our discipline is skewed to focus almost entirely on professional theatre. This skew may well have derived from our desire to unearth innovations in theatre history. We know far more about the innovative amateurs from the turn of the twentieth century – such as the Elizabethan Stage Society, the Independent Theatre Society and the latter’s continental forerunners – than we do of the everyday amateur.[Figure 3] I feel proud to be part of a group of scholars, including Claire Cochrane, Helen Nicholson and her colleagues on the AHRC Funded Project Amateur Dramatics: Crafting Communities in Time and Place, who are taking an innovative approach by setting out to redress that imbalance!

Innovation and the Society for Theatre Research

When the STR was founded in 1948 the individuals who formed its first committee were innovative in applying academic rigor to a new field – Theatre Studies. Many of the same individuals had started to produce the journal Theatre Notebook in 1945 and saw the value in bringing those interested in theatre research together in a society. It was only in the previous year that Glynne Wickham had established the first university department to focus on theatre research in Britain, at the University of Bristol. The STR was undoubtedly at the forefront of this new and emerging field.

On the STR’s website we can read of some of the organisation’s success stories. The STR played a crucial role in the twelve-year campaign for a dedicated Theatre Museum, which opened in Covent Garden in 1987 but sadly closed in 2007, with materials being transferred to the V&A’s Theatre Collections. The STR were also involved in the debates over the abolishment of the censorship of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, and fought for a clause to be written into the act which stated that the British Library would continue to be the repository for the script of every play given for public performance in Britain. The STR were also the driving force behind the establishment of an umbrella organisation for our discipline in 1957– the International Federation for Theatre Research. In fact Eileen Cottis, one of the current Honorary Members of the STR’s Executive Committee, was at that meeting where IFTR was founded.

Some scholars would argue that the STR’s days as innovative are long gone. But perhaps the Society just doesn’t shout loud enough about its success stories anymore? Arguably, the STR’s continued commitment to support innovative writing and research is one of its greatest assets!

The STR’s annual Theatre Book Prize celebrates scholarship in British Theatre. Previous winners have included Michael Billington’s State of the Nation (Faber & Faber), Jim Davis and Victor Emeljanow’s Reflecting the Audience: London Theatregoing, 1840-1880 (Iowa University Press/ University of Hertfordshire Press) and Patrick Lonergan’s Theatre and Globalisation: Irish Drama in the Celtic Tiger Era (Palgrave Macmillan). The Society is also a firm believer in funding new and original research. Thousands of pounds are given away each year to support scholars, with past awardees including the NRN’s Kate Holmes, the V&A’s Simon Sladen, the University of Glasgow’s Prof. Dee Heddon, the University of Bristol’s Dr. Catherine Hindson, and the University of Manchester’s Dr Kate Dorney.

If this isn’t its greatest asset, then it’s surely the STR’s pledge to support new talent for the professional stage through the annual Poel Event? In recent years, this event has gone from strength to strength, with workshops being led by Jeannette Nelson (Head of Voice, National Theatre), Cicely Berry (former Voice Director for the RSC), and Sir Ian McKellen.

Alternatively, it would be the STR’s investment in new and emerging scholars through the New Researchers’ Network. The NRN has built up a regular membership since it was formed in February 2012, with new and returning members coming together for study days, workshops and symposiums to share expertise, skills, approaches and knowledge. The Teaching Theatre Practice workshop was a particular success story, as it provided valuable training for researchers with very little experience of teaching practice, who may need to adapt their teaching style as our discipline becomes more and more practice-centric.

From its inception the STR has been committed to innovation in our field. While it may not have had influence over an act of parliament in recent years, today it shows that commitment through funding and supporting innovative new writing, practice and research. It therefore seems fitting that the New Researchers’ Network is asking its membership to consider their relationship with innovation – essentially that dreaded Viva question – ‘What is your contribution to the field?’. I look forward to hearing everyone’s answer to that question at the NRN’s Annual Symposium in Bristol!

How do YOU consider your relationship with innovation and your research? What new discoveries have you made in your work? Write about it for our blog: contact Emer and Kate at nrn@str.org.uk to talk about your ideas!