News

5 May 2021 / Grants and Awards

English Counter-Reformation Theatricals

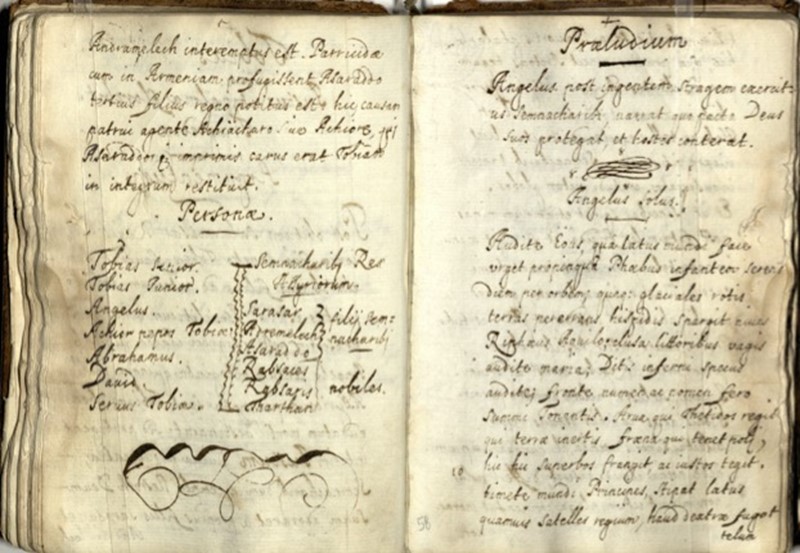

image: Tobias and the Angel, MS Lat. 32, by kind permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University

Alison Shell, of University College London, received a Research Grant in 2020 for her research into the drama of the British Counter-Reformation. She intended to travel to the Houghton Library at Harvard to look at manuscripts held there, but all plans were stopped in their tracks by the Covid restrictions. However, she was eventually able to repurpose the grant towards obtaining digital images of the most crucial manuscript. She writes for us here:

Theatre historians used to take it for granted that religious drama, so dominant in medieval England, was all but absent after the Reformation. But in recent years, they have developed a more complex understanding of how Tudor and Stuart dramatists negotiated the confessional cross-currents of their time: even in the professional theatre, where religious themes were subject to censorship. Especial attention has been given to echoes of medieval religion in Elizabethan and Stuart secular drama: an imaginative legacy exemplified by Hamlet’s father’s ghost, strongly implied to be from purgatory, though the word is never quite spoken. Through this character, Shakespeare is exploring post-Reformation unease about stopping prayer for one’s deceased ancestors.

Counter-Reformation energies also made their way into the theatre of Protestant England: often via the country’s substantial Catholic minority, educated in cutting-edge theological and cultural developments within their church. Such education often involved drama, which was — for obvious reasons – easier to mount outside England itself. The British Catholic institutions set up in Continental Europe after the Reformation – principally the English Colleges at St Omer (‘St Omers’), Douai and Rome – mounted several plays in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Typically in Latin, and often reflecting on the British Catholic experience, these trained the young performers in a range of skills valued by humanist educators, and – just as importantly — fortified them for a lifetime of discrimination and persecution. To date this corpus has been massively under-researched, thanks to a common assumption that drama written by English writers, yet not performed on English soil, is peripheral or irrelevant to the history of Tudor and Stuart drama. But interest is building, and my current project on ‘British Counter-Reformation Drama’, funded by the Leverhulme Trust, explores this fascinating corpus.

A grant from the Society for Theatre Research, supplementing the Leverhulme’s provision, enabled me to acquire a set of images from one of the most important manuscripts preserving such material: MS Lat. 32, held by the Houghton Library, Harvard University. This manuscript, which can be dated to the mid-seventeenth century, brings together a range of literary compositions from St Omers, including two plays. The first of these, Tobias sive Justus ut Palma Florebit [Tobias; or, the righteous will flourish like a palm-tree], dramatizes the story of Tobias and the Angel (above).

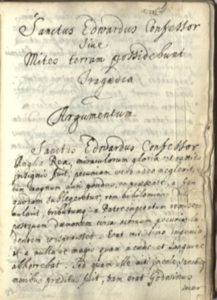

The second is an historical play, Sanctus Edwardus Confessor Sive Mites Terram Possidebunt [St Edward the Confessor; or, the meek will inherit the earth]

St Omers was run on Jesuit educational principles, and these topics are typical of the subject-matter drawn upon by Jesuit playwrights. But while biblical drama was popular in Jesuit colleges across Europe, the play on Edward the Confessor — a copy of which also survives at Magdalen College, Oxford – is more specific to the national context, testifying to college members’ intense engagement with their country’s history and their veneration of English saints. The manuscript also includes a large quantity of verse on topics ranging from the Virgin Mary’s birthday to the sufferings of England in the Civil War period, showing how drama formed a continuum with other literary endeavours.

My thanks to the STR for their generous grant; to Vanessa Braganza, Vivienne Germain and James Simpson for their help in procuring the photographs; and to the Houghton Library, Harvard University, for permission to reproduce the manuscript images above.